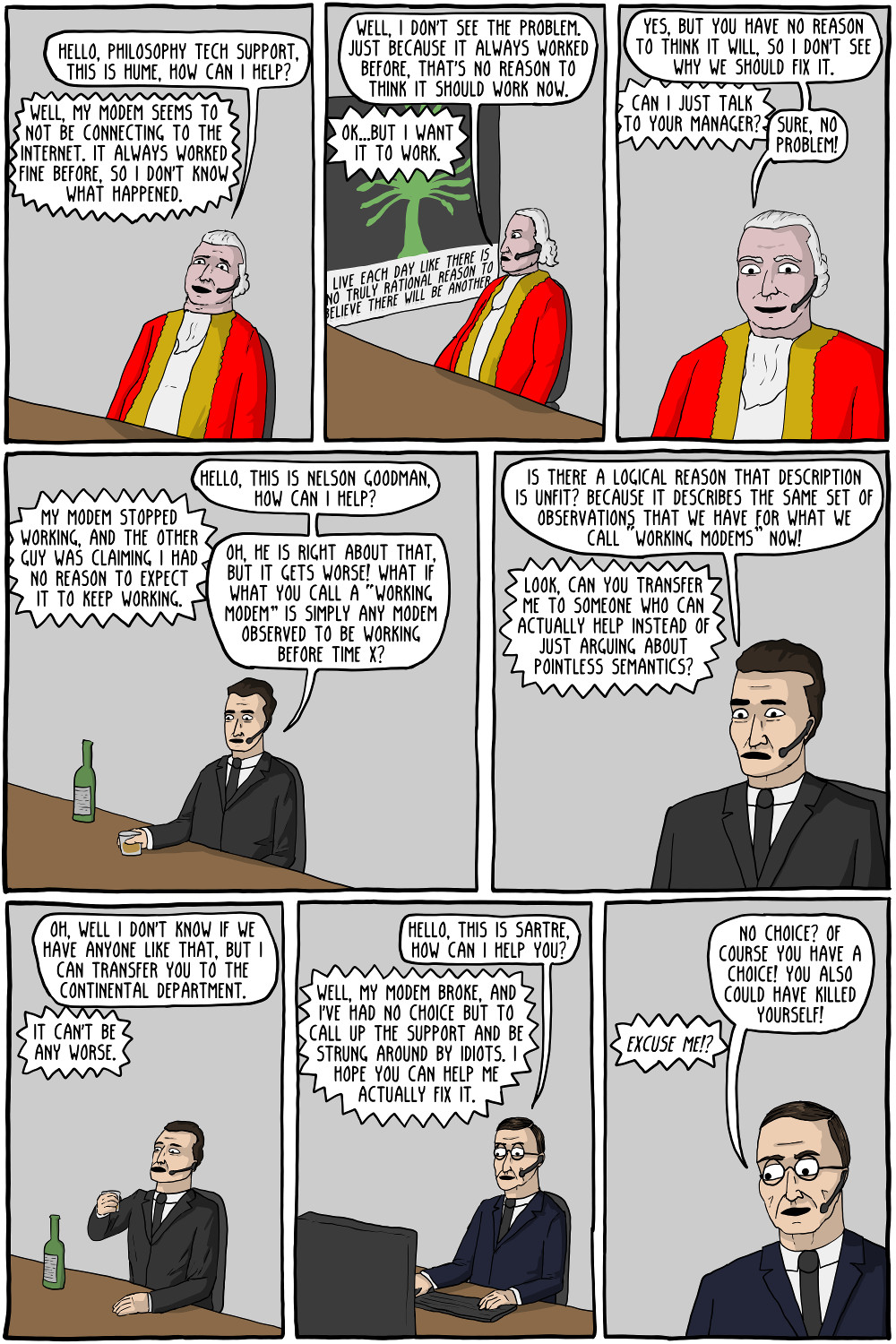

(Click through for the rest, and for a caption explaining the philosophy referenced.)

via Philosophy Tech Support – Existential Comics.

Does philosophy have a responsibility to be relevant to real world problems? This is a question often asked of science. I think the answer is complicated, because we never know where a real world solution might come from. Most of philosophy is a waste, but the problem is that there is no agreement on which part is useful and which is a waste, and you can never know when something that initially appears utterly irrelevant to the real world won’t turn out to have profound consequences.

That said, I’ve noticed a pattern in recent years with publications about scientific studies having a short blurb added explaining what its possible real world benefits might eventually be. Should philosophy contemplate doing something similar?

Many might argue that no one expects mathematical proofs to have this kind of real world application, and they’d be right. Of course, I doubt anyone would expect an abstract logical proof to have one either. It’s only when someone is attempting to apply math and logic to entities in the world where pragmatic applicability starts to become expected.

Personally, I think that both philosophy and science should be free to explore areas that might not have real world applicability, on the promise that many of those pursuits will stumble on pragmatic solutions. But I can understand the other side of this argument given never ending budget pressures.

What do you think?

What a great idea! Brilliant

LikeLiked by 1 person

I think philosophy may well become a necessary adjunct to science, just as increasingly it has in the arts. What are the questions we need to ask and how should they be formulated? What is the most intelligent and coherent hypothesis with which to commence the science? Some questions – or ‘problems’ – are self-evident, and science can proceed to find the answer to the best of its capacities. Any yet there are other questions that may not be self-evident; they only become revealed more circuitously and not via any extant problem which itself more obviously requires a solution.

So I use the term ‘philosophy’ here in the sense of developing skill in thought per se, not skills in thought about some issue or other. The development of this skill in itself, which is learning the most efficient way of thinking, has real world applicability once transferred into the mechanistic world. Many ‘real world problems’ still may benefit from addressing them with a full comprehension of the way in which they are being approached; this means whilst accounting for how they are being observed and interpreted, and how any putative solution may impact in previously un-envisaged ways elsewhere.

I suspect that you are in particular inviting your friend Tina in here SAP, so will step aside for her more detailed response, as this is her specialism of course.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Hariod. Well said. Personally, I think philosophy is already deeply interwoven into science, although some scientists may be in denial about it. You can’t really proceed with science without a framework of assumptions, many of which can’t necessarily be rigorously established scientifically. We often refer to those assumption frameworks as someone’s “philosophy”. Those philosophies are used as long as they’re fruitful and, ideally, discarded when they cease to be.

I definitely hoped Tina would respond (and I see she did), but I was thinking of you too, along with all of my other online buddies. I’m grateful for your thoughts!

LikeLiked by 1 person

SAP: “Personally, I think that both philosophy and science should be free to explore areas that might not have real world applicability, on the promise that many of those pursuits will stumble on pragmatic solutions.”

I agree to a certain extent, but philosophy can’t hand down benefits to the public the way science can. Scientists should be allowed to do research in areas that don’t seem to offer benefits for the reasons you say. However, in philosophy, each individual must do the work for himself. When people expect philosophy to be like science, when they expect to be handed down information and truths and pragmatic solutions, they will find philosophy disappointing.

Few people see the importance of doing philosophy because they think they can achieve this kind of knowledge through common sense (which, as you well know, is not very good).

I’d say that a great number of academic philosophers have made philosophy seem useless. Obscurantists abound. I decided not to pursue higher education for this reason. It’s time to prove to the public philosophy’s value, and I’m not sure allowing philosophers to argue in a vacuum will help. They’ve been doing it long enough.

Hariod: “I think philosophy may well become a necessary adjunct to science, just as increasingly it has in the arts.”

I’m sort of old school and I think science should be a handmaiden to philosophy rather than the other way around. I highly doubt this will come to pass any time soon. If philosophy became a necessary adjunct to science, that would be better than nothing I suppose.

Hariod: “So I use the term ‘philosophy’ here in the sense of developing skill in thought per se, not skills in thought about some issue or other.”

Hariod, this is exactly where I think philosophy can gain ground in the general public. I think everyone should be required to take a basic logic class. Clear articulation of thought benefits everyone in all areas of knowledge. My husband still gets letters from students, ESPECIALLY students outside of philosophy, who thank him for his logic class and say things like, “Your class changed my life.” Or, “Logic was the most useful class I’ve ever taken. It applies everywhere and has made me a more thoughtful person.”

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks Tina. Excellent points. Massimo Pigliucci (who I do respect immensely despite my latest post) once remarked that, to change the world, science only has to convince engineers, doctors, etc. For philosophy to change the world, it has to convince everyone.

I think there’s a lot to that observation, although I think philosophy can get a lot of traction by convincing the right influential people in leadership, literature, and media positions. It’s sad to say, but most people are convinced of things by hearing someone they admire espouse that view. For example, gay rights in the US made more progress from the show Will & Grace than any intellectual statements.

On logic, interestingly, I learned it from software development, which I think gives me a different view on its limitations. Often my code logic was perfect (in that the computer did exactly what I coded for), but the result was still wrong because we had misunderstood the business requirements, which itself was often due to the inherent limitations of language. In science and philosophy, the same thing can happen when we don’t understand our premises as well as we think we do.

None of this is to say that thinking logically isn’t far more powerful than thinking emotionally,intuitively, or superstitiously, only that having a periodic reality check is even more powerful.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m sure I have a far more rudimentary understanding of logic, which is what I’m thinking of in saying everyone should learn it.

The course I took wasn’t symbolic, otherwise I would have failed for sure. This one was based on Aristotelian logic in which we learned the various syllogisms, the informal fallacies, the square of opposition and that sort of thing. The pacing was very slow which allowed people like me to absorb it. (I actually looked forward to the homework…I saved it for last as “dessert” homework!) At the end we took newspaper articles and wrote them out in syllogistic form to analyze them in class. This was a real eye opener. We learned more about rhetoric than anything else…and many of us were surprised to find how many fallacies get taken as evidence to support some POV. It really did change my way of thinking…this is coming from someone not mathematically inclined, as I suspect you are.

Speaking of the limitations of language, my best friend does web development for a university now, but he used to work for a web designer (I’m not sure if I have the job titles right. The boss was the middle man between the clients and my friend). Anyhow, my friend would complain about people’s requests because they would pass through the designer (boss) and come out the other end like some garbled message from the game telephone. He said he spent most of his time figuring out what he was supposed to do, fixing errors that weren’t his fault, etc. The coding itself took no time in comparison. He found the human and language part of it really frustrating.

LikeLike

That logic course sounds fascinating. Strangely enough, I programmed for years but didn’t really apply the logic I learned to life situations. It wasn’t until graduate school, and learning about epistemology in my research methods class, that I suddenly melded the two, and subsequently started changing my views on all sorts of things from relationships to politics and religion.

On mathematics, you’d be surprised. Surprisingly for a programmer, I actually stink at anything more advanced than rudimentary algebra. Always have. But I was also always in the top tier of programmers of whatever team I worked on. Go figure. I suspect it was because programming started as something fun for me when I was a teenager but, mathematics was always drudgery forced on me by school. I *can* be dangerous with a calculator however.

Your web developer friend’s experience sounds typical. In truth, even when eliminating the middleman, there tends to be communication issues. It’s not just in programming of course. Language is notoriously difficult with the same phrases having strikingly different meanings for different people. It’s why legal contracts tend to be so obnoxious.

LikeLike

I suppose the logic of programming (well, any logic) is too divorced from real life when taken in itself. The epistemology course must’ve been a real eye opener.

I often wondered what the relationship is between logic and math, how the two are connected in the mind. I did really well in my logic course, to the point that someone asked me to study with him and we made the highest grades in the class. But math? I could vomit forth the information and make good grades, but on any sort of cumulative exam like the ACT, I’d usually finish only half the test and miss half of those answers. It was pretty dismal. I know I stink at math in general, with or without calculator. The only reason I did well in school was because I was told a series of steps to memorize.

I’ve wondered if it’s because I’m not mathematically inclined or if I never grew a “math muscle” in my brain because of school drudgery. Could it be that math teachers simply aren’t as good as English teachers, on the whole? But then how do I account for all those people who went through the same courses I did and still did well on those exams? Why did I find logic intuitive? Doesn’t add up for me unless the two things are quite different.

So funny that you say programming was fun for you…I can’t imagine it! My buddy is the same way. He actually studied music in school (he was the one who taught me how to play guitar over the phone in the 7th grade) and did programming for fun on the side. He stinks at math…he’ll ask me to calculate the tip when we go out!

LikeLike

The epistemology course did open my eyes, but it was a slow burn epiphany, taking years for the full effect to play out. (Who knows? It may still not yet have played out.)

I do think most math teachers aren’t very good at generating enthusiasm for their subject. I suspect it’s because many of them see the austere beauty of that subject, and their preference is not to sully that beauty with lots of real world examples. It’s funny, but I made it through two calculus courses in college without fundamentally understanding what calculus was and what it was used for. If my first teach had simply stated that this is how NASA plans trajectories, I would probably have been all over it.

On programming being fun, you have to understand that, for me, first there were the games, then there were bigger better games on computers, then I wanted to write my own games, which required learning to code (eventually in assembly language in those days), then much later I discovered that my game creation hobby generated skills that would make for a good career. No planning, just blind luck.

LikeLike

Ah, that makes more sense. You had fun motive for all that programming. Not for the calculus, unfortunately!

You could be right about the math teachers. They’re often so far in the stratosphere it’s degrading for them to come down to their student’s level.

LikeLiked by 1 person

The budget necessary to do philosophy is usually quite small. Asking for real world relevance is a restriction on thinking. I think the job of the philosopher is to extend the range of possible thoughts. Some, even most, of these novel ways of thinking might turn out to be nonsense or to be of little use (besindes being entertaining for some people – philosophical books may be used as literature for those of us who prefer to read such stuff instead of or in addition to novels) but you never know in advance. Sorting through those thoughts and separating the nonsense from the useful stuff is also a job for philosophers. By the way, how does one define what is useful? Who defines that?

For me, philosophy is fun (well, sometimes). Just like doing maths is fun for some people. Or doing art, or writing poems. Its not a means, its an end sometimes.

The “blurb” you are talking about exists because doing sience in most cases is expensive so people have to convince somebody to give money. For philosophy, in most cases you only need your local university library, an internet connection, maybe a park to go for walks or something like that. Academic philosophers might need a flight ticket here and there to go to a conference, but it is relatively cheap, so no blurb needed.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Good point on budgets. Science typically needs labs or field trips to difficult, dangerous, or remote locations. Still, philosophy needs money to pay salaries, and as a university administrator, I can tell you that’s almost always the biggest slice of the budget (although it never feels like it for university employees). But I think the philosophy department typically has a lot less people than, say, the electrical engineering department, and probably at substantially lower pay, so the budget point still holds.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Very nice caroon, by the way.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Everyone has collectively hit most points here.

I think some analysis of philosophical and conceptual problems really are not going to achieve anything, but yet may allow for a lot of work being done, especially as say semantic and categorization problems of everyday speech gives endless work for philosophers. For instance, as us humans move on, we may take the problem of evil under a benevolent god to be a question that should have long ago stopped being taken seriously. Also, we will dismiss the idea of someone doing endless analysis of what constitutes pass interference in American football, or some other sports problem where there is some vagueness of concept as well as a given practice surrounding the issue.

Whatever conceptually is solved by the work surrounding the problem of evil or by getting to a fine understanding of pass interference, it will more than likely not give us some useful understanding going forward. The exception is perhaps how such analysis helps us uncover the psychology of the persons engaged in such acts or the person who takes the concept too seriously (say they believe in a perfectly benevolent god). Sports referees will probably appreciate our rule cleaving, but it would be questionable what real practicality is provided. People who spent endless time solving such issues, because of motivational or other blinding mechanisms, really were wasting their time. Maybe it is both the motivation to solve and the inability to understand that the answer is not useful that makes some conceptual analysis empty.

Obviously, science has equally empty pursuits with bad motivations, and many scientists had completely wasteful careers trying to tease out bad theories that should have been dismissed before being started. Still, fundamentally, it should not be the same as some of the conceptual entanglement of some philosophical problems we erect.

I agree that problems and conceptions untangled by science and philosophy can be separated from what our immediate understanding of their usefulness is. On the other hand, there are going to be areas, especially around idiosyncratic human activity, whose unraveling we should foresee will not provide something enduring.

With that said, that all sounds a bit funny as someone who dismisses the science-philosophy distinction.

LikeLike

I appreciate your thoughts. I do credit philosophy for coming up with the problem of evil. In my mind, the problem is simple, and the solution obvious. Of course, my solution can’t be scientifically established.

The problem of pass interference I deem is equally solvable. When there’s doubt and it interferes with my team’s receiver, it’s interference. When it interferes with the other team’s, it’s not. (I doubt my solution will be appealing to anyone else 🙂 )

On you last sentence, are you observing that I dismiss the distinction between the two or stating that you do? It’s a moderately accurate view for me since I think the distinction between the two is often blurry and arbitrary, coming down to what academic department the work is being done in, although there are things that are clearly philosophy (do we have free will?) and things that are clearly science (have we detected gravitational waves?).

LikeLike

Sorry, I was merely stating my personal view. But I agree with your assessment there.

I was thinking of free will earlier as another example. For starters, I am an antirealist for free will and moral responsibility, and think there are better ways to describe human behavior and to engage interpersonal actions and dialogue than to continue such language. But fitting my earlier model, I would think in the future we may see something like libertarian free will as having been a pretty useless discussion, but also one that comes out of the idiosyncratic personal experience of being human, the way we go about experiencing making a choice, and the sloppy language that followed. In that way, much of the concept of free will has not been a useful philosophical discussion. When we move to the realm of compatibilism, what we see there is discussion about personal psychology and social organization, which is someplace that bottoms out in both science and philosophy. There are discussions there about how our discourses and institutions (say deterrence) effects human behavior. In that way, asking about what kind of selves and societies we want is useful. But much of the ontological questions and semantic decanting of the term free will may be laughed at in the future. If I am right.

LikeLike

Oh, no need to apologize. Sorry, I didn’t mean to imply any offence.

I agree with you on libertarian free will, although I’m not a convinced determinist, I still see an important social role for responsibility, and I’m okay with compatibilist uses of the term “free will” as a synonym for volition. But I also agree that much of the debate is unproductive.

LikeLike

I believe philosophy helps us question our assumptions. Our collective understanding is influenced strongly by what is habit and practice for us. But it will always be true that we are wrong about much of what we believe and that there are far more things we do not understand than we do. Through philosophy, we at least examine our ways of thinking and seek a glance of something else or more. That effort has led to amazing breakthroughs in the past, including science and physics. Logic itself is a philosophical invention, and Newton and Leibnitz’s invention of the calculus, which was pursued philosophically before it became mathematical practice, changed our world as dramatically as the computer.

So yes, let’s keep philosophers pursuing the trains of thought that intrigue them, and let’s see what we can learn about the world and ourselves.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Well said.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Great post. I loved this cartoon when i read it earlier on this week, in part because it discloses the way in which philosophy fails to conform to the needs of society. It seems to me that the uselessness of philosophy is one central element of its value. That is, part of what constitutes the value of philosophy and ultimately science is that both aim at understanding for its own sake, rather than coming up with solutions for society.

I think our technologically and commercially oriented societies have largely forgotten how to understand pursuits that are not practical, and thus I am hesitant to encourage philosophers or scientists to justify their work in terms of solving problems for society. The problem with this way of operating is that it reinforces a problematic belief that the point of knowledge is simply to solve real world problems. In so doing we only encourage the very form of thoughtlessness that threatens philosophical and scientific practise.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks. Generally I agree that knowledge is worth pursuing for its own sake. However, I don’t know that science and philosophy can completely ignore real world problems. Funding for pure science and philosophy projects is usually provided based on the recommendations of experts in the field. Those experts have credibility because their fields have provided so much benefit in the past. I doubt the LHC would have been funded if quantum physics hadn’t provided all the technological breakthroughs it did over the last 80 or so years.

LikeLiked by 2 people

I agree.

Maybe I was unclear, but I was not suggesting that science and philosophy have no role to play in dealing with real world problems. Instead I was trying to argue against merely justifying science and philosophy’s value in terms of the benefits that it generates for society, because this contributes to a problematic trend of not recognizing the intrinsic worth of these activities. But this does not mean science or philosophy cannot reference the possible social benefits that it might bring in their justification of their role in society, but this cannot be the sole basis of the justification for the reasons I pointed out.

LikeLiked by 2 people

I don’t think there’s a conflict in those perspectives. It’s like this: science and philosophy are both, at the core, a search for truth. It’s fair to assume that we will benefit from better understanding. It’s not always easy to predict “how” we will benefit. But in science at least, which is a well-tested method of progressive, inductive reasoning, we often develop expectations that ultimately pan out, once we are down to the short strokes of working out details. That’s where technologies arise and flourish. That’s the role of the LHC (if and/or until we learn something we don’t expect from existing theories, from which new theories can arise and a new plan of study can be developed).

But where philosophy and science pursue paradigm-shifting breakthroughs, the unknowns are beyond our awareness until we make some sense of them. Driven by curiosity, we keep searching. I like that about us, and our blind belief that it is, one way or another, a good thing to understand more and better..

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, and well said.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Does it have to be one or the other? That is to say, must philosophy be either useful or spectacularly detached from real world, ordinary, everyday concerns? Don’t we find both traditions represented within the history of philosophy? Stoicism is a profoundly practical philosophy; theories of the ontology of abstract entities are less practical. Both have a place.

Another consideration to keep in mind: we can think of philosophy (or any other intellectual discipline, for that matter) as being either loosely coupled or tightly coupled to underlying civilizational processes. We count something as being immediately useful when it is tightly coupled to practical concerns, but loosely coupled disciplines that produce ideas put into practice hundreds or thousands of years after their first formulation (like the use of ancient conic sections in the early modern artillery tactics) are not necessarily any less crucial to our ordinary, everyday lives.

Best wishes,

Nick

LikeLiked by 1 person

Excellent points. Of course, on the loosely coupled things, we’re somewhat operating on trust that at least some portion of those things will eventually be useful. Given the history of both science and philosophy, I think it’s a fruitful trust, but not always easy to explain.

Thanks Nick!

LikeLike