I’ve written before about split brain patients, and what they mean for consciousness. Emily Esfahani Smith has a pretty good write up on the experiments and what they showed: How An Epilepsy Treatment Shaped Our Understanding of Consciousness – The Atlantic.

The patients were there because they all struggled with violent and uncontrollable seizures. The procedure they were about to have was untested on humans, but they were desperate—none of the standard drug therapies for seizures had worked.

Between February and May of 1939, their surgeon William Van Wagenen, Rochester’s chief of neurosurgery, opened up each patient’s skull and cut through the corpus callosum, the part of the brain that connects the left hemisphere to the right and is responsible for the transfer of information between them. It was a dramatic move: By slicing through the bundle of neurons connecting the two hemispheres, Van Wagenen was cutting the left half of the brain away from the right, halting all communication between the two.

One new piece of information I got from the article was how doctors originally came up with the idea of solving epileptic procedures by, essentially, cutting the brain in half.

He had developed the idea for the surgery after observing two epilepsy patients with brain tumors located in the corpus callosum. The patients had experienced frequent convulsive seizures in the early stages of their cancer, when the tumors were still relatively small masses in the brain—but as the tumors grew, they destroyed the corpus callosum, and the seizures eased up.

“In other words, as the corpus callosum was destroyed, generalized convulsive seizures became less frequent,” Van Wagenen wrote in the 1940 paper, noting that “as a rule, consciousness is not lost when the spread of the epileptic wave is not great or when it is limited to one cerebral cortex.

If you’ve ever read a write up on the split-brain patient experiments, then much of the rest of the article won’t be new info for you, but if you haven’t, I recommend reading it in full. The descriptions of the experiments themselves get a little awkward, with the left hemisphere of the brain controlling and receiving sensory input from the right side of the body and the right hemisphere controlling and getting input from the left side, but having attempted to describe these experiments myself, I can attest that it’s hard to avoid.

The main results of the experiments were to show that:

- The two hemispheres of the brain of a split brain patient could not communicate with each other, which seems to add additional evidence that the mind does not exist independent of the brain. These people appear to have two separate minds.

- Despite this inability to communicate, split brain patients were, more or less, fully functional, except, as in the experiments, where sensory inputs to their two hemispheres were isolated. This seemed to indicate that the two hemispheres could coordinate with each other by observing what the other side did through its side of bodily perceptions.

In other words, the mind is the brain. And there is no central indivisible command center in the brain; it is a decentralized information processing cluster. The brain itself is as centralized as things get, overall, for cognition.

The split brain patient experiments are pretty mind blowing. As the article discussed, the procedure is rarely performed anymore, so opportunities for new studies are going to be limited, at least in humans. But the opportunity to do those experiments, at least for a few decades, gave us insights into consciousness that every neuroscientist and philosopher of mind must now contend with.

In the short clip, Neurologist VS Ramachandran explains the case of split-brain patients with one hemisphere without a belief in a god, and the other with a belief in a god. These studies are so fascinating, and like Ramachandran stated in the video, these findings should have sent a tsunami throughout the theological community but barely produced a ripple.

I read that Atlantic article yesterday on Godless Cranium. It was excellent.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Great stuff; I loved his book Phantoms in the Brain.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I didn’t read his book, but I have watched the BBC episodes he hosted of the same title and can be found on YouTube. 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

That is interesting, although I suspect theologians could work out an explanation of some kind. Not that it would carry any weight with nonbelievers, but then theological explanations aren’t really aimed at us anyway.

LikeLike

I love him too. I haven’t read Phantoms in the Brain, but I have The Tell Tale Brain, which I thought was fantastic.

LikeLike

What, no homunculus in my head? But it talks to me all the time Mike! 😉

LikeLiked by 1 person

That’s one of the reasons I like the attention schema theory of consciousness. It has a possible data architecture explanation for the strong intuition of the homunculus, without merely dismissing it as an illusion.

LikeLiked by 1 person

The two hemispheres of the brain of a split brain patient could not communicate with each other, which seems to add additional evidence that the mind does not exist independent of the brain. These people appear to have two separate minds.

In other words, the mind is the brain.

Not really. I am guessing by mind you mean consciousness and that is a first-person phenomena. You cannot judge from outside whether a brain is conscious or not.

LikeLike

Well, that’s true enough, but we can never know the consciousness of anything but ourselves. We can only infer it by observation of others. If we don’t allow for that inference, we’re not left with much beyond solipsism.

Once we do allow for it through, then the evidence from these experiments pretty clearly show that mental activity arises from the brain. Of course, this isn’t the only evidence for this. We also have the effects of mind altering drugs and brain damage.

Can you create a narrative around this data that still allows for a non-physical mind? Sure. But it’s increasingly unparsimonious, adding complexity to see things the way we may want them to be, rather than the way they are.

LikeLike

I am guessing we will, in the future, find a common ground between the ‘solipsism view’ and the view that ‘brain gives rise to consciousness’. Consider the cases where in-spite of being administering general anesthesia, people ‘woke up’ and were conscious during a surgery – http://www.cnn.com/2014/11/28/health/wake-up-during-surgery/. So our current technology is simply not enough to tell if a person is conscious from outside.

But one might argue that the person did lose consciousness on being administered anesthesia so there must be some relation between anesthesia and consciousness. And since the person became unconscious when anesthesia entered their body, there must be some relation between their body and consciousness. But this brings up the questions of ‘what was the cause?’ and ‘what was the effect?’. Consider the example of taking pain-killers for headaches. Does the pain always subside for everybody after taking a pain-killer? If not, isn’t that a counter-example to the theory behind that pain-killer? Why should we brush off a single person’s experience for whom the pain-killer doesn’t work and consider their case pathogenic when we come up with a theory for the pain-killer? If the pain does reduce always, which incidents before the pain-reduction do we consider as the cause for that reduction? Perhaps one might argue that we can conduct a study on a large population and if the pain reduces in a “majority” of them after taking the pain-killer then it can be concluded that the pain-killer was the cause for pain-reduction. But who decides what this “majority” is and why? Isn’t it enough if the pain-killer doesn’t work in a single case to conclude that there is something about the theory of the pain-killer and the pain its trying to reduce that we do not yet understand? I am saying that we need to enforce the scientific method more strongly. When we talk about “reproducibility” in science, we generally make do to softer extents because of logistical problems – like considering a small population for a study. So until we resolve these issues, I think we should consider the theory of the brain being a seat of consciousness just as one of several possibilities for the explanation of consciousness.

LikeLike

It’s true that, physiologically, drugs don’t always work as expected, probably due to some unusual combinations of current body chemistry and/or genetics. But taking the odd occurrence of that as disproof that they’re responsible for the observed effects in the overwhelming majority of patients in the overwhelming majority of cases, isn’t scientific.

Certainly, if someone asserted a naive theory that those drugs worked 100% of the time in all scenarios, such a theory would be falsified. But from what I’ve read of medical science, no one serious ever makes that kind of claim. Biological systems are too complex, too emergent, for any such claim.

To falsify the theory that the mind arises from the brain, you’d need reproducible evidence of the mind operating independently of the brain. Of course, many paranormalists will claim they have that evidence, but those claims have never withstood scrutiny. Mainstream neuroscience has yet to find any of that evidence. Quite the contrary, all careful reproducible evidence since the 19th century goes in the opposite direction.

Incidentally, this doesn’t necessarily rule out life after death. Early Christian theology posited a full body resurrection rather than a bodiless soul after death, and it’s not hard to imagine the information in a brain being uploaded into some heavenly version of a virtual environment. Now, I personally don’t think there is an afterlife (although it may be possible for humanity to eventually create one), but if I did, the mind arising from the brain wouldn’t be, by itself, what made me stop believing in it.

LikeLike

It’s true that, physiologically, drugs don’t always work as expected, probably due to some unusual combinations of current body chemistry and/or genetics. But taking the odd occurrence of that as disproof that they’re responsible for the observed effects in the overwhelming majority of patients in the overwhelming majority of cases, isn’t scientific.

Exactly opposite actually! Newton’s theory couldn’t explain Mercury’s orbit which was its shortcoming and the scientific community looked at it from angle as well instead of saying, “Hey, Newton’s theory works in the majority of the cases so lets not use Mercury’s orbit as a disproof for the theory”. Had we done that, we wouldn’t be using General Relativity as an accurate representation (as of today) for the phenomena we have come to call ‘Gravity’. Why does it have to be different when it comes to theories concerning our bodies? Actually, it isn’t scientific to discard some aspects of reality that don’t fit a model of reality. We should atleast acknowledge the ‘odd occurences’ and try to come up with an explanation instead of brushing them off.

Certainly, if someone asserted a naive theory that those drugs worked 100% of the time in all scenarios, such a theory would be falsified. But from what I’ve read of medical science, no one serious ever makes that kind of claim. Biological systems are too complex, too emergent, for any such claim.

I am not saying such a theory exists today but are you thinking that we will never have such a theory?

To falsify the theory that the mind arises from the brain, you’d need reproducible evidence of the mind operating independently of the brain. Of course, many paranormalists will claim they have that evidence, but those claims have never withstood scrutiny.

I am not falsifying that theory. I am just saying that we should entertain different possibilities and weigh them appropriately.

Mainstream neuroscience has yet to find any of that evidence. Quite the contrary, all careful reproducible evidence since the 19th century goes in the opposite direction.

It might be the mainstream today and I am not sure what evidence you are considering to arrive at that conclusion. But there are scientists who suggest the opposite. Here is a TED talk by someone from UC Irivine whose view I also arrived at independently: http://www.ted.com/talks/donald_hoffman_do_we_see_reality_as_it_is

It has some similarities to Berkeley’s Idealism but doesn’t use god as a starting point. People who think like this are fewer in number compared to people who think that the brain gives rise to consciousness.

LikeLike

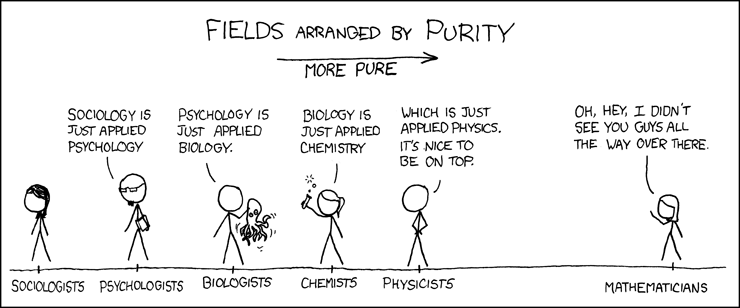

On Newton, the difference is between a theory about fundamental physics versus biology. I think this xkcd might be a good place to start:

The higher you go in the layers of abstraction from fundamental reality, the messier theories get. Science is complicated. You can’t take the methods used in one field and expect them to work, unmodified, in another. That said, it’s worth noting that general relativity accounted for everything that Newton’s theories did and then handled the special cases it failed at. For this example to hold in the anesthesia case, any alternate theory about something else causing unconsciousness has to account for the same things our current understanding of anesthesia accounts for.

“I am not saying such a theory exists today but are you thinking that we will never have such a theory?”

I can’t say for sure one way or the other. I’m not a convinced hard determinist, so I’m open to the possibility that we may never be able to have such a theory.

“I am not falsifying that theory. I am just saying that we should entertain different possibilities and weigh them appropriately.”

Maybe the difference here is in how much weight each of us gives to those different possibilities. I’m a skeptic, which tends to have me give unevidenced theories pretty low weightings.

I guess my reaction to Don Hoffman’s talk (aside from amusement for the beetle example) is the one he tried to avoid. This isn’t anything particularly new. Science has demonstrated repeatedly over the centuries that we can’t take a naive interpretation of our perceptions. But what then? How else can we know reality except through those perceptions and in light of our previous experience? Ultimately, we have no access to the reality beyond those perceptions, current and cumulative, except through those perceptions. We have no choice but to play the game. But playing the game scientifically has produced profound progress in the last four centuries. Any alternate paradigm must, again, account for the things the previously successful ones did.

LikeLike

I’ve never quite understood why various examples of damage or changes to the brain are seen as such strong evidence of non-duality. (Perhaps this is a case of both sides seeking to prove what they already believe.) We’ve known pretty much forever that brain damage changes personality (or even just wakefulness), and yet dualist theories persist.

It’s always seemed to me the evidence can be read either way:

If the brain is the entire basis of mind, then obviously physical changes to the brain must affect the mind.

If the brain is not the entire basis of mind, it still clearly has a great deal to do with it, so it’s hardly surprising physical changes to the brain affect the mind.

As a crude analogy, consider a robot with enough AI to function autonomously but which also has a link to “mission control” who can, if necessary, override behavior or upload changes to the AI program. Damage to that robot would obviously affect its behavior, but that really doesn’t say anything about mission control.

That’s how I see this situation. It seems obvious that physical changes to the brain — whether it be a sole basis of mind or not — have to affect how the mind functions.

What I’ve been pondering a lot in the last few years is a different question, and it might be one we’re closer to answering: How much of the brain’s physical and temporal properties are crucial to mind?

Put another way: Is mind strictly software (an algorithm), or does it depend to some extent on the actual hardware (and maybe even the timing of things)?

The brain has two properties that make me wonder about this. Firstly, its physical size and density of interconnections. Secondly, the brain has periodic waveforms (“brain waves”) with characteristic frequencies. Perhaps those things matter. A lot.

I’m sure you’re familiar with Searle’s Chinese Room argument. There’s another version involving the population of China, each person acting as a brain neuron. These are intended to ask “Where’s the Beef?” regarding the experiential nature of consciousness (is there “something it is like” to be the Chinese Room?).

Maybe for these systems there is no beef. Maybe, so to speak, beef only comes from cows.

And mind only comes from brains. (Which is why zombies find them so tasty. Brain beef! XD )

I find I’m more skeptical that mind is algorithmic than I am skeptic mind is brain (alone).

LikeLike

“I’ve never quite understood why various examples of damage or changes to the brain are seen as such strong evidence of non-duality.”

I think the main reason is how pervasive the scope of possible changes can be. Most people are familiar with brain injury causing loss of coordination or speech impediments, but it can also destroy someone’s ability to form and comprehend language, to understand concepts (the specific concept often depends on which part of the brain is injured). It can alter a person’s basic personality, turning a calm amiable person into an aggressive one, cause clinical depression, or social anxiety. It can destroy memories, ingrained habits, and personal inclinations. In some cases, it can cause the person to see parts of their body as being foreign, or to conclude that they’re actually dead, resisting all reason to the contrary.

Of course, many people will insist that the patient’s mind is still there somewhere, but that its access to the physical world is what is damaged. The problem with that theory is that most of us have had the experience of being intoxicated, high, or stoned at one time or another. On those occasions, I don’t recall my rational mind sitting back being frustrated while my physical self made bad decisions. I either didn’t know or didn’t care that they were bad decisions until after I had sobered up.

With all that, if there is a non-physical aspect to the mind, you have to wonder what part of our perceived self exactly resides in it. As I mentioned above, we can always make assumptions beyond observation to craft a narrative for a non-physical aspect of the mind. Those assumptions, if carefully crafted, can’t be disproven; they may never be disprovable, which puts them in the realm of metaphysics.

On mind and algorithms, I think we’ve discussed this before. Broadly speaking, I tend to think minds are algorithmic-like processes, actually massive collections of algorithms executing in parallel and interacting with each other, with the output of the system being extremely difficult, possibly impossible, to predict. Are they the algorithms of a digital computer? No, since the brain isn’t a digital processor. So, using a narrow definition of algorithm, you could say that my understanding of it isn’t algorithmic. Definitions 😛

LikeLike

“I think the main reason is how pervasive the scope of possible changes can be.”

Understood, but none of which changes my point. If the brain is crucial for mind — which it obviously is — then equally obviously changes to the brain must affect mind.

“The problem with that theory is that most of us have had the experience of being intoxicated, high, or stoned at one time or another.”

All the the above! (I’m an aging hippie, so you can just do the math there.) XD

“On those occasions, I don’t recall my rational mind sitting back being frustrated while my physical self made bad decisions.”

This, at least in my case, way overstates the idea of duality. There is no other, separate, mind that sits back and rationally observes the state of the physical mind.

Even if that were the case, how do you know? Maybe it is. Maybe that’s the source of guilt and shame the next day when you do return to your senses.

“With all that, if there is a non-physical aspect to the mind, you have to wonder what part of our perceived self exactly resides in it.”

Indeed. Perhaps it is just some sort of “spark” that causes us to rise above the other animals.

“Broadly speaking, I tend to think minds are algorithmic-like processes,…”

There’s no such thing as “algorithmic-like.” A process either is algorithmic or it isn’t. Running in parallel doesn’t change that. Interacting with other algorithms doesn’t change that. Being digital or otherwise doesn’t change that. Quantum computing doesn’t change that.

It’s been well-established that any algorithm, of any kind, can be run on a UTM.

The fundamental question, the one being posed in the Chinese Room analogy, is whether consciousness can be run on a UTM.

“Definitions”

No, it’s really not. The definitions in this case are well-established. Is there “something it is like” to be the Chinese Room?

LikeLike

On feelings of shame I feel with my hangover, I perceive there are simpler psychological and sociological explanations for it. Again, it might be different if those feelings arose with the same regularity during intoxication.

Alrighty then, algorithms 🙂

Is the Chinese Room conscious? Setting aside the consciousness of the person in the room, I don’t know. It goes to whether a system can pass the Turing test without consciousness. I think it’s conceivable. If it can do that without the architecture of inner experience, and does so, then it would not be conscious. But I think such as system could be conscious.

That said, I think we have to remember how unrealistic the Chinese Room thought experiment is, and be cautious with any intuitions we might have about it. Given its oversimplification, it seems to me an exercise designed to generate the conclusion its proponents viscerally want, that the mind simply can’t be algorithms in motion. Ultimately, I think it’s an argument from incredulity, which, given the history of science, I usually dismiss summarily.

LikeLike

“[I]t might be different if those feelings arose with the same regularity during intoxication.”

I don’t see how that means anything. Those feelings seem to have far more to do with self-awareness and how evolved ones mind is.

I would question your assertion that those feelings don’t occur with regularity. Humans are brilliant when it comes to ignoring their inner voices. (As a descriptive model, I’ve always thought there was something to Freud’s Id-Ego-Superego model.)

“But I think such as system could be conscious.”

The word “conscious” is such a tricky one, which is why I didn’t use it. You mentioned “the architecture of inner experience,” so I’m reading your answer as accepting the possibility that, yes, there “is something it is like” to be the Chinese Room.

“I think we have to remember how unrealistic the Chinese Room thought experiment is…”

Because?

“…it seems to me an exercise designed to generate the conclusion its proponents viscerally want…”

Unlike your example of getting drunk or stoned? 😀

This amounts to attacking the credibility of the people behind the argument rather than the argument itself. Of course arguments are designed to support the view of the person. So what? What matters is the coherence of the argument.

“I think it’s an argument from incredulity…”

I’m not sure it is. The C.R. analogy isn’t a failure to imagine where the consciousness lies so much as an argument that algorithmic processes don’t result in “something it is like” to be them.

But I think my main point has gotten lost here. There’s not much point in our arguing duality. We know we don’t agree on that question (although I admit to some degree of agnosticism).

As I said originally, a different question intrigues me recently, and keep in mind that this question obtains regardless of duality.

Consider a description of a laser or a microwave emitter. Such description could be “implemented” on paper, carved in stone, or stored digitally. But no description will generate coherent photons or microwaves.

Only very specific physical situations generate laser light or microwaves. A physical resonant cavity is necessary. Note that periodicity is a property of both laser light and microwaves. (And, in fact, that periodicity and the need for a resonant cavity are directly linked.)

If such simple phenomenon as laser light and microwaves supervene on specific physical conditions, it seems not unreasonable to ask whether the phenomenon of mind might supervene on specific physical conditions.

Note that periodicity is associated with the brain. Whether it’s a byproduct or a sign of a crucial foundation is an open (and I think very interesting) question.

No algorithm on its own can generate laser light or microwaves. It seems easily possible to me that mind could be like laser light or microwaves.

LikeLike

“Humans are brilliant when it comes to ignoring their inner voices.”

Sure, and we have evidence for that. But that doesn’t mean the probability of any feelings we care to speculate on occurring in our subconscious is high.

“Because?”

Because no conceivable set of manual instructions could be completed by a person in a time frame that might lead an outside person to conclude there is a conscious Chinese speaker in the room. The instructions would likely take them years, maybe decades or even centuries to complete. (A huge army of people, each serving a very specialized role, in a gigantic room, might be more feasible.)

“Unlike your example of getting drunk or stoned?”

The comparison is between an unrealistic thought experiment and a common experience. The drunk/stoned example’s point is how we experience that common situation. Of course, even if Chinese Rooms were common experiences, whether or not it demonstrated what it purports to demonstrate would still depend on each reader/listener’s intuition, which is of limited value in this area.

On the laser example, I suspect I might be missing the main point you’re trying to make. Are you saying that a mind requires instantiation in a physical substrate? If so, I agree. But I’m probably misinterpreting? (Not that we don’t occasionally agree on things 🙂 )

LikeLike

“But that doesn’t mean the probability of any feelings we care to speculate on occurring in our subconscious is high.”

I’m not sure I understand that sentence. According to psychologists, our sub-conscious is filled with feelings.

If you’re saying those feelings are not the product of some remote, separate, mind, I quite agree (and thought I’d made that clear from the beginning — outside of religious contexts, I don’t think anyone thinks that way about dualism).

“Because no conceivable set of manual instructions could be completed by a person in a time frame that might lead an outside person to conclude there is a conscious Chinese speaker in the room.”

How would it be any different from corresponding with someone in a situation where your letters took weeks to make the trip (such as we true long ago). Would you doubt someone was a Chinese speaker just because they took weeks to reply? (I have friends where sometimes weeks go by between emails.)

I think perhaps you’ve misunderstood the point of the analogy, which is that, while the person inside the room does not understand Chinese, the room appears to. This is no different than a computer programmed do to the same thing (and whose responses could be in real time). Searle is arguing that syntax does not equal semantics.

In granting that a “huge army of people” might work, we still have the same thing. (In the beginning I mentioned a similar analogy in which the entire population of China plays the role of the brain, each citizen acting as neuron.) There’s an even older version of the argument called Leibniz’ Mill.

All of these (and others) seek to refute the premise that consciousness is algorithmic. Given that we know algorithmic processes have definite limits (e.g. Turing Halting problem), these arguments do have some meat on their bones.

The key question is whether “there is something it is like” to be an algorithm or mechanical process.

“The drunk/stoned example’s point is how we experience that common situation. Of course, even if Chinese Rooms were common experiences, whether or not it demonstrated what it purports to demonstrate would still depend on each reader/listener’s intuition, which is of limited value in this area.”

Doesn’t that apply to the drunk/stoned example as well? The algorithmic process examples all present a clear model with a concrete point. I’m still not sure what the point of the drunk/stoned example is.

“On the laser example, I suspect I might be missing the main point you’re trying to make. Are you saying that a mind requires instantiation in a physical substrate? If so, I agree.”

Mind requires instantiation on a physical substrate with specific properties and may supervene on a time component as well. If a mind can be built at all, it may have to be built in a very specific way.

More to the point, mind is not purely algorithmic — it cannot be run on a UTM or any other general computing device lacking the required physical and temporal characteristics.

LikeLike

“I’m not sure I understand that sentence.”

Maybe I should have worded it as: “But that doesn’t mean the probability of any specific feelings we care to speculate on occurring in our subconscious is high.”

“Would you doubt someone was a Chinese speaker just because they took weeks to reply?”

I might if they were supposedly in a room nearby tasked with replying. Make that months or years, and my doubt leans heavily into dismissal.

“Searle is arguing that syntax does not equal semantics.”

That’s my understanding. The problem is that the argument never demonstrates that, unless you already have that intuition. If you come into the thought experiment with that intuition, it is confirmed, but if you don’t, the thought experiment is meaningless.

The point of the intoxication example is made immediately after I give it above. Obviously, given the previous paragraph, I disagree that the Chinese Room makes a concrete point. If it does, I’m afraid I need it spelled out for me more…concretely 🙂

“More to the point, mind is not purely algorithmic — it cannot be run on a UTM or any other general computing device lacking the required physical and temporal characteristics.”

Conceivably, although I’m far from convinced of that. But if true, that doesn’t mean we couldn’t eventually learn to build such a physical system. If it happens in nature, and doesn’t require astronomical energies, I think asserting that we can never ever do it requires justification.

LikeLike

“Maybe I should have worded it as:…”

Yeah, that didn’t help at all. 🙂 Since this seems an important point to you, and given that I don’t get it at all, perhaps it’s worth starting its own discussion in a new thread.

“I might if they were supposedly in a room nearby tasked with replying.”

Suppose you were told that room contained a two-way radio linking you to a Chinese speaking person in the fringes of the solar system (so expect major delays in replies)?

“I disagree that the Chinese Room makes a concrete point. If it does, I’m afraid I need it spelled out for me more…concretely”

It’s considered a focal point in discussions about theories of consciousness, so it is well worth understanding both sides of the argument. It’s an unresolved issue among those who devote their lives to the study of consciousness which is a pretty good indication that both sides have merit. At this point, I think being dismissive of either side is a mistake.

The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy has a very good article that explores both sides of the argument in pretty good detail:

http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/chinese-room/

Given that the experts don’t agree, we’re not going to settle it here, and I only brought it up as a context setter for a possible discussion about the dependence of mind on specific physical and/or temporal requirements.

“I’m far from convinced [that mind is not purely algorithmic].”

Yes, I know that. XD

“But if true, that doesn’t mean we couldn’t eventually learn to build such a physical system.”

Absolutely. My only point is that mind may not be solely algorithmic. The physical nature of the machine on which it runs may be crucial (as it is with lasers and microwaves).

“If it happens in nature, […] I think asserting that we can never ever do it requires justification.”

Absolutely. I’ve made a similar argument many times. We know nature creates brains (and the minds that supervene on them), so it might be just an engineering problem. (OTOH, the jury is still out on whether it might be more than an engineering problem. Until the jury returns, I intend to hope for more.)

I see Asimov’s “Positronic brain” (which Star Trek paid homage to with Cmndr. Data) as much more likely than an algorithm running on a general computing device.

Or it may be that neural nets — which simulate the brain — will work. They also can demonstrate a periodicity very similar to brain waves.

It’s hard to imagine that circuit density would be a factor, but it could turn out to matter. Perhaps all those neurons (biological or otherwise) firing in a confined space gives rise to a sort of highly complex standing wave important for consciousness.

Maybe, if you spread a person’s neurons out over a large area, consciousness would cease. There are projects attempting to simulate the architecture of the human brain, so we might have some answers in a decade or so.

LikeLike

“Suppose you were told that room ”

I think I’ll bail on this Whac-A-Mole 🙂

Yes, lots of serious people take the CR seriously. But lots of other serious people think it’s meaningless. I agree with the latter, and additional reading about it has only strengthened that initial conclusion. I don’t plan to spend more time investigating it unless someone gives me a compelling reason to reconsider.

I either agree or have no objection to the rest. On brain periodicity, I sometimes wonder if it is in any way similar to the memory refresh that is constantly taking place in semiconductor DRAM chips. (No assertion here; just idle speculation.)

LikeLike

“Yes, lots of serious people take the CR seriously. But lots of other serious people think it’s meaningless. I agree with the latter, and additional reading about it has only strengthened that initial conclusion.”

If you have a clear vision of the right answer, that’s great. I find both sides make some pretty good points, so it’s not clear to me at all.

“I either agree or have no objection to the rest.”

Given your belief in the algorithmic nature of mind, I would have thought you might since it argues that mind is not mere software but may supervene on specific physical characteristics.

LikeLiked by 1 person

The higher you go in the layers of abstraction from fundamental reality, the messier theories get. Science is complicated. You can’t take the methods used in one field and expect them to work, unmodified, in another.

Well actually the opposite is found to be true more and more. We are finding that concepts in one field of science can be used in another. Ex:

http://nautil.us/issue/12/feedback/ants-swarm-like-brains-think

http://www.washington.edu/news/2014/04/10/fruit-flies-fighter-jets-use-similar-nimble-tactics-when-under-attack/

http://engineering.stanford.edu/news/stanford-biologist-computer-scientist-discover-anternet

And I would expect that. But yes, many people do think that the theories in Chemistry must totally be different than theories in Psychology. I think, nature could eventually defined by a single set of laws. We just haven’t got there yet. Obviously I am not the only one thinking like this. Otherwise, our efforts towards a Theory of Everything are just useless.

That said, it’s worth noting that general relativity accounted for everything that Newton’s theories did and then handled the special cases it failed at. For this example to hold in the anesthesia case, any alternate theory about something else causing unconsciousness has to account for the same things our current understanding of anesthesia accounts for.

Ofcourse. But Newton also believed in Absolute Space and Absolute Time which were essential for his theory which are no longer considered true. Newton’s was a model about the phenomena called Gravity. And models keep improving. General Relativity was a better model for Gravity than Newton’s Law of Gravitation. Newton also believed that god periodically pulled back Earth from falling into Sun, even though he didn’t incorporate that into his theory. Similarly, we have a phenomena where conscious beings become unconscious which is intervened by a number of events, administering anesthesia into the body being one of them.

I can’t say for sure one way or the other. I’m not a convinced hard determinist, so I’m open to the possibility that we may never be able to have such a theory.

On the one hand you believe in mind-uploading and on the other you are not completely a hard-determinist. Isn’t that contradictory?

We have no choice but to play the game. But playing the game scientifically has produced profound progress in the last four centuries.

I am a hard determinist. So I believe that when we invent or discover, we are still following laws of reality. Otherwise, I would have to believe in supernatural stuff which I don’t.

LikeLike

A Theory of Everything could unify fundamental physics, but it wouldn’t solve all the problems in other fields.

I suspect we may be using different definitions for “hard determinism”. I think the best thing here would be to refer you to my post on this subject. It doesn’t involve anything supernatural, just particle physics and chaos theory.

LikeLike

When I meant “Theory of Everything”, I did really mean Everything! So not just Physics but other fields too. You think we won’t have such a theory?

I went through your post of hard determinism. I don’t want to argue about that but rather what I meant to say was that we are not in control of ourselves otherwise there wouldn’t be things like “mental illness” in this reality. Again, you cannot brush of a mentally ill person because they are ill and hence they are not in control of themselves. Because when they think they regain control back after taking medications, its not that the medication is giving them back freewill is it? I know there are many definitions of freewill but here by freewill I mean “controlling ourselves”. When we suffer pain unintentionally, especially emotional pain, we are certainly not controlling ourselves.

LikeLiked by 1 person

That’s an interesting distinction. Conceptually, as I understand it, a physics theory of everything would be an all encompassing theory of everything, assuming reductionism is accurate. The question is, would we ever have the processing power to apply it to higher level problems such as chemistry, biology, sociology, etc? Theoretical physicist Sean Carroll has pointed out that, despite all the evidence in its favor, we can’t use the Standard Model of particle physics to predict the periodic table of elements. It may be that the limits of computing power will always frustrate an attempt to make higher level predictions with a theory of everything.

Of course, all of the above assumes we can get a theory of everything. Max Tegmark, in his book ‘Our Mathematical Universe’ points out that forming a theory of everything might require data from regions of reality that we can’t access (such as the inside of a black hole). So I could see us maybe never getting it. That said, I don’t think it would be productive to ever assume that.

On free will, I feel we’re on much the same page. I think the mind exists in this universe and is wholly dependent on the laws of nature for its operations. Despite that, I think social responsibility remains a coherent concept, albeit one that should be tempered with mercy given the fact that none of us have full control of our life circumstances. Even if hard determinism is true, responsibility would still be a causal influence for healthy informed minds. Whether to say those healthy informed minds have “free will” seems a matter of definition.

LikeLike

Okay… this drunk/stoned example… It started with:

“Of course, many people will insist that the patient’s mind is still there somewhere [under brain injury], but that its access to the physical world is what is damaged. The problem with that theory is that most of us have had the experience of being intoxicated, high, or stoned at one time or another. On those occasions, I don’t recall my rational mind sitting back being frustrated while my physical self made bad decisions. I either didn’t know or didn’t care that they were bad decisions until after I had sobered up.”

This assumes:

A rational mind distinct and separate from the brain.

That such a mind would be frustrated by inebriation.

That your “brain mind” would be directly aware of its frustration.

That feelings many do have along those lines don’t arise from this other mind.

That all others share the lack of knowing or caring you describe.

All of those are big assumptions. (Considerable personal experience invalidates the last point.)

The picture you’re painting seems somewhat like many religious people think of as a “soul” and in many of those cases, there is no sense the soul is a rational thinking entity.

In the paragraph that follows you ask where the non-physical aspect to the mind might reside, which is a strange question coming from one who believes so much in emergent behaviors.

Later, I wrote: “Humans are brilliant when it comes to ignoring their inner voices.” You replied:

“Sure, and we have evidence for that. But that doesn’t mean the probability of any feelings we care to speculate on occurring in our subconscious is high.”

To which I replied, “Huh?” 🙂

I asked if what you meant was: “[T]hose feelings are not the product of some remote, separate, mind, I quite agree […].” You replied:

“But that doesn’t mean the probability of any specific feelings we care to speculate on occurring in our subconscious is high.”

Which still leaves me going, “Huh?”

I don’t see how this is a response to the basic premise or the questions I posed: Given that the brain is clearly crucial for mind, why is it surprising that changes to the brain result in changes to the mind?

If this is intended to refute the idea of a separate rational mind, then I quite agree, but I also never suggested any such thing.

LikeLike

“The picture you’re painting seems somewhat like many religious people think of as a “soul””

That is pretty much what I was addressing. If it’s not your conception, then no worries. But I don’t think it’s a “big assumption”; it’s the most commonly held conception of dualism. I don’t know many people who hold your sophisticated and nuanced ideas on it.

“Which still leaves me going, “Huh?””

Contrary to what you said above, this point isn’t really important to me. I don’t think it’s worth additional energy. (Unless it’s become important to you?)

“I don’t see how this is a response to the basic premise or the questions I posed: Given that the brain is clearly crucial for mind, why is it surprising that changes to the brain result in changes to the mind?”

That was the premise? If so, then I wouldn’t think it would be surprising. But I started off responding to this one (quoted from your initial comment above):

“I’ve never quite understood why various examples of damage or changes to the brain are seen as such strong evidence of non-duality.”

LikeLike

“If [the religious conception of soul is] not your conception, then no worries.”

In my first reply: “This, at least in my case, way overstates the idea of duality.” And later: “[O]utside of religious contexts, I don’t think anyone thinks that way about dualism.”

Just to be clear, “that way” refers to the idea of a separate, rational mind passing judgements on ones corporeal behavior.

“I don’t know many people who hold your sophisticated and nuanced ideas on it.”

Plenty of people listed here:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dualism_%28philosophy_of_mind%29

You written about forms of dualism in the past:

https://selfawarepatterns.com/2014/05/26/the-dualism-of-mind-uploading/

“Unless it’s become important to you?”

No, I just couldn’t understand your responses, and I wanted to. In productive discussions I think it’s important to be clear what the other person is saying.

One point should be clarified:

“But I don’t think it’s a “big assumption”; it’s the most commonly held conception of dualism.”

That’s not what I said. I listed five bullet points that I claimed were big assumptions. If you thought they aren’t, then you’d demonstrate why not. (Or challenge me to explain why they are.)

“That was the premise? […]”

The sentence you quote was from my initial comment. I think the premise is clearly stated in the first four paragraphs of that comment.

LikeLike

Wyrd, it seems like this discussion has devolved into pettifoggery, for which I accept my share of the blame.

I perceive two differences of opinion here. One is in how likely we regard the possibility of some version of substance dualism. Given my skeptical impulses, I see the probability as pretty low, but I’ll admit the probability is not zero.

The other seems in our attitude toward the mind being algorithmic. I personally see little reason to doubt that it is, but I’ll admit that we’re unlikely to know for quite some time.

This is an area where we have to on guard against our desires. Many people want the mind to transcend the brain so that something of us continues after death. Many singularitarians want the mind to be entirely physical so we have a chance at engineering immortality. My own sense is that humanity has a chance of eventually engineering immortality, but probably not soon enough for anyone alive today; many skeptics who come to the same conclusion then seem to want it to be forever impossible, since no one wants to be the last mortal.

If you haven’t already, I do hope you’ll read that post on the dualism of mind uploading.

LikeLike

I wouldn’t call asking someone to clarify their words — or to engage with I actually said — “pettifoggery” and I find the idea vaguely insulting. That we have well-known areas of disagreement ought to make a debate more interesting, but maybe that’s just me.

What I thought would be interesting is talking about how the mind might supervene on specific physical characteristics of the brain. (And I wanted to understand why you think being drunk is a data point, ’cause I’m just not seeing it.)

“This is an area where we have to on guard against our desires.”

I’ve begun to recognize this as a favorite card you like to play. It doesn’t have the trump value for me that it seems to with you. The whole point of the dialectic — and of science — is to nullify that bias.

Chalk it up to one more thing we just see very differently.

LikeLike

Here’s a very interesting TEDx talk you might enjoy. The brain scan images are especially cool, and what a striking thought: Psychiatrists are the only doctors who frequently (as in almost never) actually look at the organ they’re treating!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Wyrd! That was interesting.

Although, I was a bit uneasy with his dispersions against psychiatry. When someone disses an entire field, I’ve learned to see it as something of a red flag. So I googled him. You might find this write up on him at the Washington Post interesting.

https://www.washingtonpost.com/lifestyle/magazine/daniel-amen-is-the-most-popular-psychiatrist-in-america-to-most-researchers-and-scientists-thats-a-very-bad-thing/2012/08/07/467ed52c-c540-11e1-8c16-5080b717c13e_story.html

Turns out the field doesn’t think well of him and that he’s got a major financial interest in what he’s selling in the talk.

From what I’ve read elsewhere, psychiatry is moving toward a brain centric paradigm, but whether we know enough yet for it to be useful in clinical settings is fiercely controversial.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yeah, I didn’t want to prejudice your viewing with my own opinion. There is also that he gets a little “Evangelical” towards the end of his talk. That’s often a red-flag for me.

That said I don’t place much weight on linking financial success or establishment resistance with the validity of claims. It’s all about proof and actual value provided. It would be interesting to know what kind of success rate he’s had (he, of course, touts his notable ones).

Psychiatry is still sort in the leeches and witch doctor era, plus “Big Pharma” sees a billion dollar industry in pills and potions. So there’s seriously vested interest on both sides. Don’t show me the money; show me the proof!

He does say some things I thought were very interesting, and the brain scans were really cool. If they do correlate well with reality, seems like they could be useful.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I totally agree that financial success doesn’t, by itself, invalidate what he’s claiming. But it does give him a vested interest in a certain outcome. Coupled with his purported unwillingness to submit his findings to peer review, my suspicion is pretty high.

I agree that evidence is the key distinction. Do the scans correlate with reality? Not being an expert in brain scanning, I can’t evaluate it. But some of the other articles I found on him, written or endorsed by people I’ve found to be fairly knowledgeable on neuroscience topics in the past, aren’t encouraging. http://neurocritic.blogspot.com/2012/08/the-dark-side-of-diagnosis-by-brain-scan.html

LikeLike

Yeah. As you frequently point out, both sides have vested interests — both money and reputation in this case — so I tend to discount all opinions (including, foremost, my own). It’s all about what can be shown to be true.

The thing about iconoclasts is some of them, maybe even the bulk fraction, are kooks (or worse), but every once in a while you do get a Copernicus or Einstein. (And it’s usually bloody hard to tell the difference at first.)

About all I can say about this guy is that it’s interesting. Psychiatry is certainly a field that has room for growth and improvement!

LikeLiked by 1 person