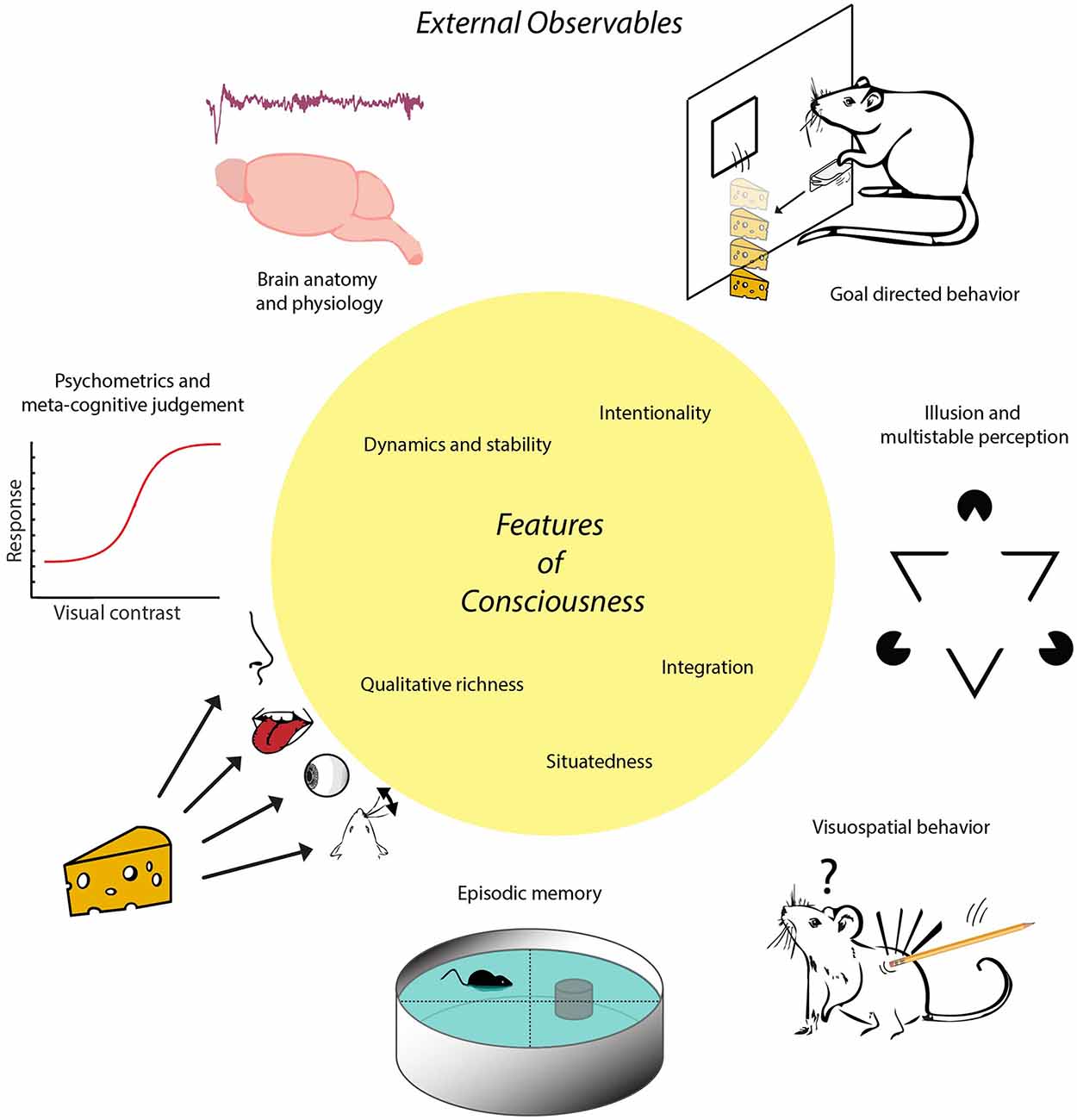

An interesting paper came up in my feeds this weekend: Indicators and Criteria of Consciousness in Animals and Intelligent Machines: An Inside-Out Approach. The authors put forth a definition of consciousness, and then criteria to test for it, although they emphasize that these can’t be “hard” criteria, just indicators. None of them individually definitely establish consciousness. Nor does any one absent indicator rule it out. But cumulatively their presence or absence can make consciousness more likely or unlikely.

Admitting that defining consciousness is fraught with lots of issues, they focus on key features:

- Qualitative Richness: Conscious content is multimodal, involving multiple senses.

- Situatedness: The contents of consciousness are related to the system’s physical circumstances. In other words, we aren’t talking about encyclopedic type knowledge, but knowledge of the immediate surroundings and situation.

- Intentionality: Conscious experience is about something, which unavoidably involves interpretation and categorization of sensory inputs.

- Integration: The information from the multiple senses are integrated into a unified experience.

- Dynamics and stability: Despite things like head and eye movements, the perception of objects are stabilized in the short term. We don’t perceive the world as a shifting moving mess. Yet we can detect actual dynamics in the environment. The machinery involved in this are prone to generating sensory illusions.

In discussing the biological function of consciousness, the authors focus on the need of an organism to make complex decisions involving many variables, decisions that can’t be adequately handled by reflex or habitual impulses. They don’t equate consciousness with this complex decision making, but with the “multimodal, situational survey of one’s environment and body” that supports it.

This point seems crucial, because the authors at one point assert that the frontal lobes are not critical for consciousness. Of course, many others assert the opposite. A big factor is whether frontal lesions impair consciousness. There seems to be widespread disagreement in the field about this, but at least some of it may hinge on the exact definition of consciousness under consideration.

The authors then identify key indicators:

- Goal directed behavior and model based learning: Crucially, the goal must be formulated and envisioned by the system. People like sex because it leads to reproduction, but reproduction is a “goal” of natural selection, not necessarily of the individuals involved, who often take measures to enjoy sex while frustrating the evolutionary “purpose”. On the other hand, formulating a novel strategy to woo a mate would qualify.

- Brain anatomy and physiology: In mammals, conscious experience is associated with thalamo-cortical systems, or in other vertebrates with their functional analogs, such as the nidopallium in birds. But this criteria largely breaks down with simpler vertebrates, not to mention invertebrates or artificial intelligence.

- Psychometrics and metacognitive judgments: The ability of a system to detect and discriminate objects is measurable and, if present, the organism’s ability to assess its own knowledge.

- Episodic Memory: Autobiographical memory of events experienced at particular places and times.

- Illusion and multistable perception: Susceptible to sensory illusions (such as visual illusions) due to intentionality, the building of perceptual models.

- Visuospatial behavior: Having a stable situational survey despite body movements.

I’m not a fan of relying too much on 2, specific anatomy, at least other than in cases of assessing whether someone is still conscious after brain injuries. As I noted in the post on plant consciousness, I think focusing on capabilities keeps us grounded but still open minded.

I don’t recall the authors making this connection, but it’s worth noting that the same neural machinery is involved in both 1, goal planning, and 4, episodic memory. We don’t retrieve memories from a recording, but imagine, simulate, reproduce past events, which is why memory can be so unreliable, but also why we can fit a lifetime of memories in our brain.

I was initially skeptical of the illusion criteria in 5, but on reflection it makes sense. Experiencing a visual or other sensory illusion means you are accessing a representation, even if not a correct one, so a system showing signs of that experience does indicate intentionality, the aboutness of experience.

The authors spend some space assessing IIT (Integration Information Theory) in relation to “the problem of panpsychism”. They view panpsychism as cheapening the concept of consciousness to the point where the word loses its usefulness, and see IIT as “underconstrained” in a manner that leads to it. (I saw a comment the other day that IIT gets cited as much in neuroscience papers as other theories like GWT, but at least in my own personal survey, most of the citations of IIT seem to be criticisms.)

Finally, the authors look at modern machine learning neural networks and conclude that they currently show no signs of consciousness. They note that machines may have alternate strategies for accomplishing the same thing as consciousness, which raises the question of how malleable we want the word “consciousness” to be.

There’s a lot here that resonates with the work surveyed by Feinberg and Mallatt, which I’ve reported on before, although these indicators seem a bit less concrete that F&M’s. They might better be viewed as criteria for the development of more specific experimental criteria.

Of course, if you don’t buy their definition of consciousness, they you may not buy their criteria for indicators. But this is always the problem with scientific studies of ambiguous concepts.

So the question is, do you buy their description? Or the resulting indicators?

h/t Neuroskeptic

Looks to me that they just took what human beings associate with consciousness and created a list of its characteristics. So the animals (mainly mammals) that seem to have sensory apparatus and some complexity in their behavior like us make the cut and nothing else. This really doesn’t tell us much new.

LikeLike

On starting with humans, I think that’s what everyone has to do. Healthy developed humans are the only category that everyone incontrovertibly accepts as conscious. The question then is always, what in the way humans process information is necessary and sufficient for the label “consciousness”?

The authors don’t rule out non-mammalian consciousness (or machine consciousness). They do make clear the limitations of the anatomical criteria. I think it’s an interesting question for pre-mammalian species like reptiles, amphibians, and fish. They are missing considerable capabilities that mammals and birds possess. Is what they do have still sufficient? I’m not sure there’s a fact of the matter.

It is a fair point that what’s new here is a bit limited. But the illusion criteria is a new one for me.

LikeLike

I think consciousness needs to be derived from principles that are not just lists of what we think human consciousness is. Then it could be shown how humans or the characteristics humans have meet the criteria by the items in the list. There has to be something new or unexpected in the criteria.

I don’t have any idea what the principles would be but I expect it would answer, for example, whether Boltzmann brains are conscious. It should be able to do this as a theoretical exercise even if you think Boltzmann brain can’t exist. Or, if we took a brain from a body disconnected it from its sense organs and put it in a vat could it report experiences, assuming we had some way of capturing it. If it reported experiences, would it be conscious? This would be similar to the Matrix scenario where the entire experience is a simulation. Was Neo conscious before he took the red pill?

It seems to me that experience itself or having experience is the main criteria and the sense criteria are just an indirect way of determining that there is experience happening. But using experience as a criteria may be no more than just using a different term for consciousness and so accomplishes nothing.

LikeLike

By the way, Hoffman would be enthusiastic probably about the illusion criteria.

His book Visual Intelligence spends a lot of time on visual illusions and I think when he began focusing on that is when he came to the conclusion that all of our representations of the world are illusions and that is very nature of consciousness. The book is good even if you don’t want to buy into the larger implications.

LikeLike

On deriving consciousness from a list of principles without reference to human consciousness, how would we go about establishing such a list? How would we validate it? If we remove the information from human consciousness, how do we even know consciousness exists?

On Hoffman, I wasn’t aware that he had that book. Pity it’s not available electronically. As I’ve noted before, I do think he’s right that a naive interpretation of senses does not give us the world as it is. (Among science oriented people, I don’t think that’s controversial.) It’s possible that not even a sophisticated interpretation does either, but it’s all we get. We can only judge our models by how well they predict future experiences.

You’re probably aware of this, but Hoffman has a new book coming out Tuesday, which appears thoroughly oriented toward his large selling point, that reality is an illusion.

LikeLike

“On deriving consciousness from a list of principles without reference to human consciousness, how would we go about establishing such a list? How would we validate it?”

If you are trying to find consciousness in something not human, how can you use a list that is only derived from humans? Fundamentally a human oriented list is only going to find organisms substantially similar to humans to be conscious.

There’s a similar problem either way you go.

Any human-oriented list could miss alien forms of consciousness, either ones on other planets or ones even on this planet, that don’t conform to the human norms.

It seems to me that consciousness involves a representation of reality and perhaps a sense of self experiencing the representation. I don’t see how you can demonstrate that by external characteristics or traits. A Boltzmann brain or a brain in a vat likely would be conscious by this criteria even though they had no actual sensual input and could take no action in the world, although they could believe they are receiving sensual input and are taking actions. This might also be compared to a dreaming brain.

I’m aware of the new Hoffman book and am expecting it from Amazon. Visual Intelligence is available new for $14 or so and used for around $4. It’s not like one of those $110 text books.

“It’s possible that not even a sophisticated interpretation does either, but it’s all we get. ”

Careful. You’re getting dangerously close to idealism with that. 🙂

LikeLike

Given the constraints you’re imposing, I don’t see how a scientific study of non-human consciousness would be possible. The only consciousness we ever have access to is our own. We never have access to any other, except by what we can infer from behavior. If we can’t start there, then I can’t see how we can start anywhere else.

Due to our anatomical similarities, It seems reasonable to accept that other healthy mature humans are conscious. We can find the correlations between their self report of experience and exercising of specific capabilities. We can then find those same or similar capabilities in non-human animals and infer some similar degree of experience. Which brings us to frameworks like the one in the paper, or others like the ones Feinberg and Mallatt discuss.

“Careful. You’re getting dangerously close to idealism with that.”

I’ve never understood how idealism doesn’t collapse into solipsism. If we doubt the external world, then why don’t we doubt the existence of other minds? Maybe I’m the only mind and you’re all an illusion, or maybe you’re the only mind and the rest of us aren’t here.

In the end, all we have are conscious experiences and theories. We can only assess the theories by how well they predict future experiences. The existence of a mind independent world seems to make accurate predictions. What testable predictions do we get from assuming it’s all an illusion?

LikeLike

Both Hoffman and Kastrup believe there is an objective world. Hoffman calls it his approach conscious realism. Your “mind independent world” is an unnecessary assumption since it is not required to make predictions, especially since predictions are made by the mind.

LikeLike

What do they mean by “objective world” if it’s not independent of minds? And if mind independence is an unnecessary assumption, how do we explain hurricanes, earthquakes, or disease? How does medicine work if we dispose of mind independent things like viruses and bacteria?

LikeLike

Their argument is that there is a mind outside your mind and my mind. The objective world is mind too. Effectively it comes into existence relative to us as we measure and perceive it.

Their argument.

LikeLike

Thanks for clarifying it. Sounds like Berkeley idealism, which is inherently theistic.

LikeLike

Yes. Very similar. But I wouldn’t bring a deity into the picture. Substitute quantum reality and you would be closer to Kastrup’s view anyway.

LikeLike

Once we start talking about the reality outside of us all being a mind, it’s pretty hard to avoid theology.

But even if it’s true, that mind appears to operate according to pretty consistent regularities. We’re back to Einstein’s “understanding the mind of God”, with science and all the rest. If we stay compatible with scientific observations, at some point the differences are in danger of collapsing into language preferences.

LikeLike

The mind at large in Kastrup’s version is not like a designer or planner of the universe even though those are attributes we might associate with mind. It is more like units of raw experience. There is no overall understanding. It provides order as an outgrowth of its nature not as part of a master plan.

His argument is that it more parsimonious to posit the underlying reality is mind than anything else since inevitably mind must come into the picture at some point.

LikeLike

What would you say distinguishes Kastrup’s view from naturalistic (monistic) panpsychism?

The thing to remember about parsimony is that we still need to be able to make predictions with the same accuracy as the more complex theory. If we can’t do that, then we’ve crossed from parsimonious to simplistic.

LikeLike

Frankly I am not inclined to spend a lot of time trying to scope out all of the nuances of each variation of ontology.

The number one prediction that any idealism makes that is a “hard” problem for anything else is that consciousness exists. The days when idealism could be refuted by kicking a stone have gone by the wayside since the stone itself has dissolved into a quantum haze.

LikeLike

Fair enough. But I do wonder how much difference there really is between an actual rigorous idealism and physicalism. They’re both monism.

LikeLike

There is an important point you touched upon Mike which underwrites Bernardo’s “strategy” for his version of idealism, and that is solipsism. According to Bernardo, without his extravagantly complex ontology, with all of its unique and sophisticated analogues, idealism ultimately collapses into solipsism.

LikeLike

I’m curious what specific aspects of his ontology inoculates against the collapse into solipsism. I’ve never seen how arguments for idealism don’t lead to it.

LikeLike

“The days when idealism could be refuted by kicking a stone have gone by the wayside since the stone itself has dissolved into a quantum haze.”

So true James. In light of the intrinsic paradoxes underwriting both materialism and idealism, I really don’t get why highly intelligent, sophisticated human beings are still content debating the same old arguments. I mean, how long can one whip a dead horse before the stench of its rotting carcass becomes offensive? From what I’ve witnessed, the answer is indefinitely… same shit, different day.

LikeLiked by 1 person

“I really don’t get why highly intelligent, sophisticated human beings are still content debating the same old arguments.”

Because it’s fun. 🙂

LikeLike

“I’m curious what specific aspects of his ontology inoculates against the collapse into solipsism.”

That’s just it Mike, there aren’t any. His entire architecture is built upon analogies and analogues. The most famous or infamous analogy (dependent upon one’s own perspective of course) that Bernardo uses to support his thesis is a mental disease known as “multiple personality disorder” or “dissociative identity disorder” (DID). But hey; whatever flies one’s kite because there’s something for everyone, just keep shopping.

LikeLike

Oh, this is that guy. Thanks Lee!

LikeLike

Buying their scheme is not necessary. It is a reasonable place to start, however. By implementing this scheme, we will get data we can critique and analyze. It is always better to do … and think, than just think alone.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Definitely. And an argument can be made that, in any case, we can still establish whether specific cognitive abilities are present, regardless of whether we can agree if those abilities are necessary for consciousness.

LikeLike

That fifth feature is an interesting one. It’s a good trick to build an internal model of reality that differentiates the agent’s movements within that model from movement of non-agent parts of the model. You can kinda see why it might be prone to being fooled. (Machine vision, equally, is a trick that’s hard to pull off and therefore subject to interesting failures.)

In general, the criteria seem to pick out how consciousness creates a dynamic internal model, which seems like a good approach.

LikeLiked by 1 person

It also makes me think about HOT (higher order theories). If the model we hold in our mind is separate from the raw sensory one, then that seems to point to a separate model behind that initial “first order” sensory one, a secondary or “higher order” one. Although it says nothing about where that higher order model is, or even if it’s necessarily completely distinct from the first order one.

LikeLiked by 1 person

“On starting with humans, I think that’s what everyone has to do.”

I do not necessarily disagree with this statement Mike. However, one must be willing to propose the correct question, and so far, neither functionalists nor instrumentalists are asking the appropriate question. Like it or not, that conclusive question is grounded in metaphysics and is as follows: What is the one “proprietary” feature of human consciousness that is the difference which makes all the difference when contrasted against other forms of consciousness?

With this question, one can now garner the data to be critiqued and analyzed.

LikeLike

Lee,

So you’re asking not what the one proprietary feature of consciousness is, but what the one proprietary feature of human consciousness is? The history of people declaring what that is, is a pretty dismal one, with the answers not standing the test of time. Many things asserted to be unique to humans have shown up in non-human animals, such as tool use, planning, theory of mind, metacognition, and many others, although humans do these things with a sophistication far in excess of our animal cousins.

My current answer, at least until someone finds them in another animal, is symbolic thought, built on top of recursive metacognition. (Note: according to the definition the paper authors use, my answer might be outside of consciousness.)

LikeLike

“…is symbolic thought, built on top of recursive metacognition.”

Clearly, your current answer itself is open to rigorous critique and in the end will not stand up under the scrutiny of analysis. Symbolic thought, built on top of recursive metacognition is not unique to homo sapiens. The only thing that is unique are the biological features which allow homo sapiens to express symbolic thought, built on top of recursive metacognition.

According to Thomas Metzinger, what is unique about human consciousness, and the difference that makes all the difference is that for the first time in the entire evolutionary process of the universe as we know it, “consciousness; as a phenomenon is aware of itself”. That spooky, outstanding and significant distinction should be thoroughly critiqued and analyzed.

LikeLike

I think it is important to recognize the unique capabilities of humans. Part of it is the recursive metacognition and symbolic thought we seem to agree on. And I do think it enable us to have a much more thorough self model than any other species on Earth. (Although the accuracy of that model is a different matter.)

But anytime we manage to reason ourselves into thinking we’re somehow special in some cosmological manner, we have to be on guard. History shows how easy it is for us to fool ourselves. Human consciousness knowing consciousness is undoubtedly special…to human consciousness.

It’s also worth mentioning another important thing humans have that most species don’t, one that is just as important for our ability to spread into all the niches we have: hands. When thinking about how important the intellect is, don’t forget about the hand.

LikeLike

Hey, can I have a go?

I suggest the difference that makes a difference is the ability to generate large numbers of arbitrary concepts. I think that’s what we got from all that extra neocortex. Among those arbitrary concepts would include arbitrary goals, plans, and associations. It’s the associations of sounds (and later images) with other concepts that give us language. It’s the association of our goals and plans with other animals (robots?) (especially other people) that gives us Theory of mind. Other species have some of these abilities, but it is the new scale at which we have it that allows for language and complex culture.

*

LikeLike

I think this paper does a service in recognizing that consciousness is ill-defined and that there are multiple indicators. I think it does a disservice in its presentation of 5 features of consciousness in that (I think) not all of those features are requisite for consciousness. As others have said, they just seem to be features of human consciousness. So …

“1. Qualitative Richness: Conscious content is multimodal, involving multiple senses.”

Clearly multimodality can’t be requisite for consciousness, if for no other reason than we could take away each modality one by one without losing consciousness (until you take out the last one).

“2. Situatedness: The contents of consciousness are related to the system’s physical circumstances.”

Not all contents of consciousness are related to the system’s physical circumstances. I can consciously contemplate a mathematical problem, say 232 x 14, and work out a solution without ever involving my physical circumstances.

“3. Intentionality: Conscious experience is about something, which unavoidably involves interpretation and categorization of sensory inputs.”

This is the linchpin. Intentionality is the one thing necessarily part of every act of consciousness. And never mind the sensory inputs part, unless you want to categorize your awareness of the number 232 as “sensory”.

“4. Integration: The information from the multiple senses are integrated into a unified experience.”

First, I think this concept of a “unified experience” is flawed, almost certainly illusory, and generally unhelpful. Second, I agree that integration of information, in the form of conceptualization, which I take to be the combination of multiple intentional inputs into a single combined intentional input, is ubiquitous in conscious experience not by definition but by the fact that it is the most and possibly only useful thing you can do with primary intentional content.

“5. Dynamics and stability: Despite things like head and eye movements, the perception of objects are stabilized in the short term. […] The machinery involved in this are prone to generating sensory illusions.”

Understanding of dynamics and stability of objects in the environment are simply an example of the useful things you can do with proper integration of information as described immediately above.

So again, I say that the common denominator of consciousness is intentional content, and all the various indicators described in the paper are indicators of various ways intentional content is used by a system.

*

[now I have to dive into all of those old posts about F&M, apparently. 🙂 ]

LikeLiked by 1 person

“I think it does a disservice in its presentation of 5 features of consciousness in that (I think) not all of those features are requisite for consciousness.”

Remember that the authors don’t intend for the criteria to be “hard”, that is, all necessary or by themselves sufficient. They’re only suggested indicators. It’s fully recognized that all of them will have exceptions and caveats. (They actually write a page or two on each one, far too much detail for me to cover in a brief post.)

“Not all contents of consciousness are related to the system’s physical circumstances.”

They don’t have to be, but arguably most of them are. Even the ones that aren’t tend to be within metaphors of those immediate sensory impressions. And it’s worth noting that while machines can easily use encyclopedic knowledge, their ability to take in knowledge from their immediate environment and use it is still lacking in major ways. Self driving cars can use navigational knowledge to get through city road systems, until, reportedly, they come to a construction site.

“And never mind the sensory inputs part, unless you want to categorize your awareness of the number 232 as “sensory”.”

Can you conceive of the number 232 without an image of some type coming up? I either see the Arabic numerals, or a point on a number line, a ratio of some type, or something similar. In other words, every way I can think of it, involves a sensory metaphor of some type.

“First, I think this concept of a “unified experience” is flawed, almost certainly illusory, and generally unhelpful.”

I actually considered making a comment about the unified experience aspect in the post. I agree it may largely be illusory, something we perceive because we’re not conscious of the gaps in our consciousness. I held off because, well, we do perceive it.

But I agree the integration aspect is actually more important for functionality, which, unlike unified experience, can be observed or tested for.

“Understanding of dynamics and stability of objects in the environment are simply an example of the useful things you can do with proper integration of information as described immediately above.”

I think that’s too reductive. Certainly it’s built on integration, but if we get greedily eliminative in our reduction, we’ll eventually be left talking about quantum fields. And as I indicated to Wyrd, it might be giving us clues to the representational architecture of the mind. So I wouldn’t dismiss this one.

I do agree that intentionality is the major component of conscious experience. There’s just a lot involved in producing it.

“[now I have to dive into all of those old posts about F&M, apparently. 🙂 ]”

If you do, go easy on me on the old posts. I’ve learned a lot since then. 🙂

LikeLike

Mike, given that our entire mental apparatus evolved to interact with the physical world I’m not going to argue or expect that a significant number of experiences are unrelateable to some sensory modality. For every abstraction for which we have a word, like “justice”, or “suspicion”, or “infinity”, there is a visual, and usually auditory “image” which often pops up, but not necessarily. Also, (I am saying) these are correlations unrelated to causation, specifically the causation of the experience. It is facts like these, correlations like these, which make it difficult for people to understand the ontological nature of experience.

For example, I assume you were giving the self-driving car story assuming said car is not conscious. I would challenge you to explain why the car is not conscious, but a rat heading to a place in a maze where it remembers finding food is conscious.

“but if we get greedily eliminative in our reduction, we’ll eventually be left talking about quantum fields.”

We only need to reduce down to the point where we’re explaining intentionality, representations. We get there long before we get down to quantum fields, and once we have gotten there, there is no point in going lower. To paraphrase I’m not sure whom, you should be as reductive as possible, but not more reductive than that.

*

.

LikeLike

“Also, (I am saying) these are correlations unrelated to causation, specifically the causation of the experience.”

So, are you saying the imagery is epiphenomenal (in a weak spandrel like sense)? If so, given I can’t catch myself thinking of 232 without imagery, am I actually conscious of holding the “real” 232 concept?

“I would challenge you to explain why the car is not conscious, but a rat heading to a place in a maze where it remembers finding food is conscious.”

Well, I would start off by saying there’s no fact of the matter on which is conscious. Neither processes information exactly the way we do, although the rat is a lot closer than the car.

But let’s compare them. Both have reflexive reactions to certain stimuli. (The rat’s evolved, the car’s programmed.) Both build models of the environment, although the rat’s are built from photons striking its retina, vibrations shaking its Cochlea, chemicals stimulating its olfactory sensors, as well as the somatosensory feel of the terrain. The car’s are built using radar, lidar, and GPS.

The rat has an interoceptive network of sensors throughout its body, including very sensitive whiskers. It has the ability to detect any impingement on, or damage to, its physical body. Many of its reflexive reactions also generate changes in its bodily state, which it receives information on. In other words, it feels many of its reflexive reactions. From what I know, if the car has anything like interoception, it’s far more limited.

The rat appears to have the ability to imagine future scenarios, remember episodic events, and respond dynamically to changes in its environment, such as the arrival of a predator. It’s situational survey is much more comprehensive and its ability to use it is far superior. In other words, the rat has imagination.

I haven’t read anything to give me the impression the car has that yet. Its map of the environment seems much more tied to fixed action patterns than the rat’s. The car does have an ability to learn, but that ability is far more limited and fragmentary.

Finally the rat has its own selfish genes. It’s primarily concerned about its survival and reproduction, as well as the survival of its pups and perhaps other kin. It strives to maintain its own homeostasis. A car doesn’t care whether it exists or is replaced by next year’s model. It might react reflexively in some ways that serve to protect its passengers, but it doesn’t actually know those passengers exist.

So, we could say that the car has a limited form of exteroceptive consciousness, although at a far lower resolution than the rat’s, but no interoceptive or affective consciousness. I’m not sure if exteroception plus reflexes rises yet to most people’s intuition of consciousness.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Heh. I didn’t (mean to) say compare the consciousness of a car in general to the consciousness of a rat in general. The rat was clearly designed to be long-term self sufficient in its environment. I was just referring to the consciousness involved in navigating to an imagined place. But let’s look at your comparisons.

“Both have reflexive reactions to certain stimuli. (The rat’s evolved, the car’s programmed.)”

I don’t know for a fact, but I’m guessing much of a car’s reactions are based on neural networks, and so, learned in a way that is similar to evolution.

“The car’s [models] are built using radar, lidar, and GPS.”

Tesla’s also use cameras.

“From what I know, if the car has anything like interoception, it’s far more limited.”

Cars have temperature sensors, tire pressure sensors, gas and/or charge sensors, gear shift sensors, gas/brake pedal sensors, passenger weight sensors, various engine sensors. ‘Nuff said.

Here I will impute the entire functionality of a GPS system to the car. The GPS not only gives a suggested route, it provides alternative routes. Presumably an automated car will follow the suggested route, but that route can change in the middle if incoming data suggests that a new route is faster. A passenger may be given the option to choose one of the alternatives. The car also responds dynamically to changes in its environment, such as the car in front of it slowing to a stop, or a pedestrian entering the street. A rat has a wider range of behaviors, but so what? The car still has imagination.

Do you think a rat cares about whether it exists? The rat just acts the ways it was “programmed” to. Just like the car. The car avoids contact with things, thus maintaining homeostasis. The car warns you when it’s running out of juice, thus maintaining homeostasis. In what sense does a rat “know” its pups exist? Do they contemplate their futures? Do they reminisce about the last batch of pups? They know they (the pups) are things out there in space, and they know what actions to take under what circumstances. How is that different from knowing that a passenger exists at a certain address and knowing what actions to take to move to that address?

Um, no interoceptive consciousness? [points to line above ending in “Nuff said”]

Affective consciousness? Not yet maybe, but it would be pretty easy to implement. (If it’s raining, decrease standard speeds by 5%, turning speeds by 20%, adjust fans on windshield to de-fog, etc.)

*

LikeLike

“I don’t know for a fact, but I’m guessing much of a car’s reactions are based on neural networks, and so, learned in a way that is similar to evolution.”

I obviously don’t have access to the source code of these systems, but from what I’ve read, the core of the system is rule based. Machine learning is used for fine tuning. It might be equivalent to fragmented local operant conditioning, but not global operant conditioning. A car can’t learn how to navigate through a construction zone on its own.

“‘Nuff said”

That’s just random sensors with isolated monitoring systems. I’ve seen nothing to indicate that it’s all integrated into a body image map the way it is in animals. That’s not to say someone couldn’t take a shot at it, but having it all integrated in that fashion, while it might eventually be productive, probably isn’t a priority right now for those engineers. (At least I haven’t read anything about them doing it yet.) And it would be at a far lower resolution than what the rat has.

On the GPS and autobraking, you’re taking very narrow optimized tasks, ones involving no actual imagery, and calling it “imagination.” I think that requires such a deflated conception of imagination that the term loses its meaning. Again on the construction zone, the car has no ability to think through how to navigate through it, or to deal with many other novel complexities.

“Do you think a rat cares about whether it exists? The rat just acts the ways it was “programmed” to. Just like the car. ”

Again, I think you’re excessively deflating terms like “care” and “homeostasis”. By that line of reasoning, humans are just responding the way they are programmed. From a certain point of view, that might be true, but it’s hand waving away enormous complexity.

“Affective consciousness? Not yet maybe, but it would be pretty easy to implement. (If it’s raining, decrease standard speeds by 5%, turning speeds by 20%, adjust fans on windshield to de-fog, etc.)”

What you’re describing as pretty easy would be reflexes, not affective consciousness. An affect is not the reflex, but the representation of the possible reflex for input into imaginative simulations or for use in assessing them. Affects require imagination, and vice versa.

Imagination, including affects, is hard. If we knew how to do them, we’d have much more intelligent robots than currently exist.

LikeLike

Regarding interoception: “no interoception” is different from “some interoception, but organized differently for obvious reasons”. You had said “no interoception”.

Also, you refer to integration into a body map. In what sense do you see integration into a body map, as opposed to finding locations in neocortex in which relative locations correspond to relative skin locations. I’m not sure what you mean by Integration here.

Regarding affective consciousness, I think I have know idea what you mean by that phrase, especially as it applies to imagination. Need a li’l help.

*

LikeLike

[also, no idea]

LikeLike

“I’m not sure what you mean by Integration here.”

Just that all the interoceptive information is brought together into a body image. Mammalian brains have that in their brainstem, elaborated in their insula and somatosensory cortices.

“Regarding affective consciousness, I think I have know idea what you mean by that phrase, especially as it applies to imagination. Need a li’l help.”

Consider the stipulation you made above about intentionality being the core component of consciousness. There is the reflex, then there is a model, a representation of that reflex, which we call the affect. Initially that representation forms in the cortex from a signal from the sub-cortical reflex that it is about to fire. The frontal lobes can allow or inhibit that reflex. To decide whether it will, it runs scenario-action simulations, each of which in turn have a low level affective reaction, which in turn either allow or inhibit that scenario. Eventually one of the scenarios comes out on top, whereupon any reflex in conflict with it is inhibited and any compatible with it allowed.

Imagination can’t work without valuation, the valence provided by the affects. And affects only exist to feed the imagination engine. They are two sides of the same coin.

“[also, no idea]”

Not sure what you’re referring to here.

LikeLike

I’m still not happy with how you are using integration. In what sense is this “body image” treated as one thing?

Regarding affect, I still have know idea (also, no idea, 🙂 ) what you mean. You suggest an affect is a representation of a reflex, said representation formed in the cortex. What exactly is represented, i.e., what is the intentional object? The input stimulus? The entire event, including output, which may or may not be suppressed?

It’s possible my hang-up is that I have a very particular notion of affect and it’s effect on consciousness. To me, affect refers to emotions, and emotions are essentially states which have systemic physiological effects, usually due to something like the level of a specific hormone in the blood. Certain perceptions can induce a change (Tiger!) to the levels of various hormones, and these changes can then change our perceptions (Shh, I think I heard a tiger.). We can also detect these changes via interoceptive perceptions. We, being humans with the ability to create arbitrary concepts, can conceptualize a particular suite of such interoceptive perceptions and give a name to that conceptualization, such as “fear”. I can see how that conceptualization can be represented, or modeled, by a particular module in cortex. (I suspect cortical column = module).

So is this in any way compatible with how you are using affect?

*

LikeLike

“In what sense is this “body image” treated as one thing?”

It allows the system to respond collectively to multiple signals. For example, I wish my car could look at the outside temperature when deciding whether a change in tire pressure is something to be concerned about. It has both sensors, but there’s no integration. Of course, a rat’s integration if far more comprehensive.

On affects, the interoceptive resonance you describe is definitely part of it. The idea that it’s based only on interoception is James-Lange theory, but I think that theory was formed before we had all the spinal cord injury survivors we have today. People whose spinal cord has been severed around the neck reportedly have reduced emotional feelings, but still have them, indicating that the interoceptive loop isn’t the sole source, although the vagus nerve is intact so it’s always possible something’s coming in there.

Affects certainly are emotions, but they also include more primal feelings usually not labeled as emotions (although I have seen it) such as hunger, pain, etc. Emotions are usually more complex and probably involve a lot more cortical real estate.

What do the representations include? Good question. Honestly, I’m not sure. It might be better to describe them as association clusters. All I can say is that based on what I’ve read, they seem to be clustered in the ventromedial prefrontal cortex and the anterior cingulate cortex, although I’m sure they’re also in other regions. The lobotomies in the mid-20th century typically severed connections with the vmPFC.

LikeLike

So are you saying

1. you require this kind of integration for consciousness? (Basing tire pressure directions on external temperature and current tire pressure)

2. Choosing the shortest route among several would not qualify as integration?

*

LikeLike

I do think integration is a crucial aspect of consciousness, but it’s not the only one. And I don’t think the capabilities that trigger our intuition of consciousness can be reduced to one factor. (Which is why you usually see me present a hierarchy.)

I don’t think the GPS function of choosing the shortest route qualifies as imagination, at least not in the sense of performing sensory-action simulations. Certainly the overall GPS system does integrate information, and I guess you could regard that as a sort of consciousness, but it’s very different from the immediate environment awareness and homeostasis concerns of creature consciousness. I don’t think it will trigger most people’s intuition of a conscious entity, not that those intuitions are necessarily consistent or rational.

LikeLike

There’s nothing intuitive about the relation between water and hydrogen and oxygen, but the knowledge is necessary to understand all of the wonderful forms of water, and why water works as it does. And that’s not enough knowledge by itself to explain snowflakes, but it’s a start.

And when someone says an self-driving car is not conscious, because they don’t see anything they intuit as part of consciousness, I see it as some person from a tropical climate who has never heard of snow or ice being shown a pile of snow, and being told that it’s just water. I don’t think they will believe you, at least not until they see it melt.

*

LikeLike

You’re assuming there’s a fact of the matter of whether a self-driving car is conscious. As I indicated above, I don’t think there is. Only its specific capabilities, or lack thereof, are objective facts. You can say those capabilities amount to consciousness. Someone else can insist they’re not close enough to animal or human capabilities. How can you say they’re wrong? Or how can they say you’re wrong? What evidence or logical necessity can either of you marshal to prove what amounts to a definitional preference?

LikeLike

For what it’s worth, I do find Metzinger’s synthetic a priori judgements regarding consciousness intriguing to say the least. Because when it comes to the scientifically verified phenomenon of quantum entanglement, it appears that spooky action at a distance could be the prevailing underlying architecture. And if that scenario is correct, the only condition that would accommodate non-locality and quantum entanglement would be a linear, continuous system of some kind, one that is not subordinate to either time or space, a system in itself which would actually be responsible for the very phenomenon of both space and time. The only linear, continuous system which has the potential to satisfy that criteria would be consciousness.

So, maybe what we really need to do is rethink the entire framework of this thing we refer to as “consciousness” by distancing ourselves from our own first person experience of it. Surely, the experience itself prejudices our ability to objectively analysis it, does it not? Corresponding to the reality/appearance distinction and in contrast to idealism, consciousness would not be analogous to mind, but merely a linear, continuous system which the discrete systems of appearances run on. This model, with its underlying architecture of consciousness would supersede the necessity for the prevailing model which relies upon the notion of physical laws.

From my perspective, the notion of laws is much more absurd than the notion of consciousness, a condition which entails meaningful relationships predicated upon reciprocating correspondence between discrete systems as they engage in the choreography of mutual creation and destruction in an endless dance. Is this not what actually occurs between two consenting adults, or is there a physical law of some kind which governs that relationship?

LikeLike

That gets into the free will debate. Myself, I don’t think we have contra-causal free will, although I’m on board with various compatiblist conceptions. So to answer your question directly, I think what occurs between consenting adults ultimately is governed by physical laws, although attempting to use those laws to in any way predict what might happen is silly.

Although attempting to use psychological knowledge, essentially those laws at a much higher abstraction, to make probabilistic predictions is not only practical, we do it all the time in our social interactions.

LikeLike

“I think what occurs between consenting adults ultimately is governed by physical laws, although attempting to use those laws to in any way predict what might happen is silly.”

You painted yourself into a corner big time with your comments Mike, so I’m going to let you off the hook by not pressing the issue. One final anecdote: The notion of physical laws apply across the board to any and all discrete systems without exception, or they apply to none. Human beings are not special. The notion of law is a fairy tale and the most deeply entrenched delusion that our own creative, vivid imaginations have ever concocted. If there is an intellectual construction which stands as a monument of obstruction and suppression, it is the notion of law.

LikeLike

“You painted yourself into a corner big time with your comments Mike, so I’m going to let you off the hook by not pressing the issue.”

If I made an error, I’d prefer you point it out to me. One of the reasons I blog and discuss this stuff is to see if there are holes in my reasoning.

LikeLike

In order to paint yourself out of the corner Mike, you first have to identify which physical laws “govern” successful relationships between two consenting adults and second, if that relationship ultimately breaks down and is unsuccessful, is that the result of one or both of the individuals violating or breaking those physical laws? And if that is the case, do other discrete systems also possess the capacity to break the physical laws which govern their relationships with other discrete systems; say, the earth orbiting around the sun for example? Or are homo sapiens an exception to the law of physics and therefore special?

In addition to that conundrum; as an antecedent to the notion of law, is not the objective of identifying physical laws the ability to make accurate predictions? So in that context, predicting what might happen between two consenting adults would “not” be silly if the entire relationship was predicated upon something a simple as physical laws.

LikeLike

Lee,

You’re asking me to hop over numerous layers of abstraction. The fact that I can’t do so only points to the complexity James discussed in his comment.

Instead, I think I’ll just wait for the paint to dry. 🙂

LikeLike

Lee, are you familiar with Wolfram’s book: A New Kind of Science? I’m not a mathematician, and so I just trust that he shows what he says he shows, because math. But my take home is this: you can have a system that follows a very small set of rules. Wolfram uses cellular automata, so just a simple grid. (Actually, I think he uses a one dimensional grid, so just a line of cells.). He looks at different sets of rules which determine whether any given cell is on or off, depending on the current state of its neighbors. What he found was that there are some sets of rules (laws) which make it essentially impossible to predict far in to the future whether any given cell will be on or off. The predictions could be done, but the resources needed to make that prediction would be greater than the resources needed to just run the system that far and see.

If our universe runs on a small(ish) set of rules that behave in a similar way, it would require more resources than exists in the universe to predict any outcome sufficiently far into the future. Thus, a smallish set of laws can be compatible with a relation between consenting adults, and said relationship may have been inevitable since the Big Bang, but it would be practically impossible to determine in advance whether there there would be a break up in that relationship or not, and there would not need be any violation of the smallish set of laws in either case.

*

LikeLiked by 1 person

In fact, materialism is essentially the belief that reality is a cellular automata operating according to a set of rules (the standard model + gravity + some stuff that still puzzles us, like dark matter and dark energy).

LikeLike

“Instead, I think I’ll just wait for the paint to dry.”

I would not have expected any other response Mike.

“What he found was that there are some sets of rules (laws) which make it essentially impossible to predict far in to the future whether any given cell will be on or off. The predictions could be done, but the resources needed to make that prediction would be greater than the resources needed to just run the system that far and see.”

Cellular automata with its own unique set of rules (law) is a brilliant deflective strategy to employ when one does not have the answers to fundamentally simple questions. Like: “Yeah, let’s make it so difficult so that nobody can understand, then people will have to rely upon the priesthood for the answers.” It’s an effective strategy employed by the hierarchy of every church for thousands of years, and that tradition is alive and well within the church of science today. “God works in mysterious ways, please send money.”

I think I’ll lay the cellular automata head trip on my six year old nephew next time I have to break up a fight between the two siblings.

LikeLike

Hey, Mike: Did you know this post doesn’t show up in the WP Reader? Your older posts do, but not this one. Anyone else notice this, or is it just me? (It’s true on all my devices.)

LikeLike

Hey Wyrd. Thanks for letting me know. When I go and look, I’m seeing it. Of course, I’m me, so maybe I’m seeing some privileged version?

In general, I find the WP reader to be temperamental. Sometimes stuff I post doesn’t show up for hours, and I’ve had a few posts over the years that I’m not sure ever showed up. Lately I’ve even had some stuff take a long time to show up on the blog home page, which always makes me wonder if I’ve done something wrong.

Sometimes if I make a minor edit and hit Update, things shake out, but not always.

I know there’s a tag limit. But unless it’s using some weird way to count, I rarely get anywhere near it. I’ve also heard tampering with your post timestamp can cause issues, but I never touch that.

LikeLike

Same with me it doesn’t show up in the followed sites part of the reader, although if I go to conversations in the reader I can see it. And your site is followed so that’s not the problem.

But this has happened with other posts by you too. I thought maybe it was something controlled in the publishing options.

LikeLike

Thanks James. Just got with WordPress support. They cleared a caching issue on my feed, so it should show up now. I did point out the ongoing issues and they said they’d investigate. Let me know if it still isn’t showing up.

LikeLike

Now it shows up!

LikeLike

Good deal. Thanks!

Hopefully if I’m doing something wrong they’ll set me straight.

LikeLike

Your most recent post showed up, so I think you’re good. (I suppose I should follow myself and make sure the same thing hasn’t happened to me.)

I have noticed there’s a delay between posting and when that post shows up in the RSS feed. I’ve always wondered why.

LikeLike

Thanks!

Although I follow you in the Reader, the straight RSS feed is usually how I see your posts. I do notice sometimes that the feed takes a while. Sometimes your post doesn’t show up in my feed reader until several hours after it’s been out, although that might be more InoReader’s cadence in checking it. It seems to vary with each blog. Some show up instantly. One (not yours) often takes days to show up unless I explicitly refresh it.

LikeLike

Yep, I’ve noticed all the same things. (And it is the RSS feed that’s delayed. I’ve probed the URL directly.)

LikeLike

Shows up now also.

LikeLike

Thanks James!

LikeLike