Philosopher Wilfrid Sellars had a term for the world as it appears, the “manifest image.” This is the world as we perceive it. In it, an apple is an apple, something red or green with a certain shape, a range of sizes, a thing that we can eat, or throw.

The manifest image can be contrasted with the scientific image of the world. Where the manifest image has colors, the scientific one has electromagnetic radiation of certain wavelengths. Where the manifest image has solid objects, like apples, the scientific image has mostly empty space, with clusters of elementary particles, held together in configurations due to a small number of fundamental interactions.

The scientific image is often radically different from the manifest image, although how different it is depends on what level of organization is being examined. For many purposes, including scientific ones, the manifest image, which is itself a predictive theory of the world at a certain level or organization, works just fine. For example, an ethologist, someone who studies animal behavior, can generally do so without having to concern themselves about quantum fields and their interactions.

But if the manifest image of the world is how it appears to us, how do we develop the scientific ones? After all, we only ever have access to our own subjective experience. We never get direct access to anything else.

The answer is that we start with those conscious experiences, sensory experiences of the world, and we work to develop models, theories, of how those experiences relate to each other. (We sometimes forget that “empiricism” is just another word for “experience.” One comes from Greek, the other Latin.) We judge these theories by how accurately they’re able to predict future experiences. It’s the only real measure of a theory, or any kind of knowledge, we ever get.

But often developing these theories, these models, requires that we posit aspects of reality that we can’t perceive. For example, no one has ever seen an electron. We take electrons to exist because they’re crucial to many theories. But they’re most definitely not part of the manifest image.

So the theories give us a radically different picture of the world from what we perceive. Often those theories force us to conclude that our senses, our actual conscious experience, isn’t showing us reality. The only reason we take such theories seriously, and give them precedence over our direct sensory experience, is because they accurately predict future conscious experiences.

Of course, there are serious issues with many of these theories. Two of the most successful, quantum mechanics and general relativity, aren’t compatible with each other. And there’s the measurement problem in quantum mechanics, the fact that everything we observe tells us that there is a quantum wave, until we measure it, then everything tells us there’s just a localized particle.

These are truly hard problems, and solving them is forcing scientists to consider theories that posit a reality even more removed from the manifest image. It’s why we get things like brane theory, the many worlds interpretation of quantum physics, or the mathematical universe hypothesis. If any of these models are true, than the ultimate nature of reality is utterly different from the manifest image.

But as stark as the distinctions between the manifest and scientific images are or could be, it’s not enough for some. Donald Hoffman is a psychologist and philosopher whose views I’ve discussed before. Hoffman has a new book that he’s promoting, and it’s putting his views back into the public square. This week I listened to a podcast interview he did with Michael Shermer.

Hoffman’s main point is that evolution doesn’t prepare us to accurately perceive reality. That reality therefore can be very different than what our perceptions tell us. But Hoffman is going much further than the typical manifest / scientific image distinction. He contends that there isn’t even a physical reality out there. There are only minds. Our perception of reality is a “user interface” that enables access to something utterly alien in nature. Even the various scientific images don’t reflect reality. These are just more user interfaces.

What then is the ultimate reality? Hoffman appears to believe it’s consciousness all the way down. In my last post on Hoffman, I labeled him an idealist, in the sense of thinking that the primary reality is mental rather than physical, and I still think that’s the right description.

Although in the Shermer interview, he says he does think there is an objective reality. Based on what I’ve heard, he sees this objective reality existing because there’s a universal mind of some sort outside of our minds thinking about it, a view that seems similar to the subjective idealism (and theology) of George Berkeley, where objective things exist because God is thinking about them.

How does Hoffman reach this conclusion? He starts with the fact that natural selection doesn’t seem to favor an accurate perception of reality, just an effectively adaptive one. He tests this using mathematical simulations which reportedly tell him that there’s zero probability of natural selection selecting for accuracy.

Here we come to my issues with this idea. Hoffman is using an empirical theory (natural selection) along with empirically observed results of simulations, to conclude that empirical observations aren’t telling us about reality. But if all of reality is an illusion, then how can he trust his own observations? In the interview, he assures Shermer that he avoids this undercutting trap, but if so, it doesn’t seem evident to me.

The second issue is that Hoffman is taking this insight and apparently making a major logical leap to conclude that it leads to much more than the manifest vs scientific image distinction. The established scientific images exist because they’re part of predictive models. Extending these images to another level requires additional models and evidence, and those models must explain the successes of the previous ones. Hoffman owns up to this requirement, but admits it hasn’t been met yet.

My third issue is that Hoffman’s stated motivation for positing this idealism is to solve the hard problem of consciousness. Per the hard problem, there’s no way to relate physics to consciousness, so maybe the solution is to do away with all physics.

But there is an easier solution to the hard problem, one that doesn’t require radically overturning our view of reality. That solution is to recognize what many psychological studies tell us, that introspection is unreliable, including our introspection of experience.

This too is a sharp distinction between the manifest image and the scientific view. The problem, of course, it’s that this version isn’t emotionally comforting. Like Copernicanism, natural selection, relativity, and quantum physics, it takes us ever further from any central role in reality.

Which brings me to my fourth issue with Hoffman’s view. It’s a radical view that’s emotionally comforting, seemingly positing that it’s all about us after all. Of course, just because it’s comforting doesn’t mean it’s wrong, but it does mean we need to be more on guard than usual against fooling ourselves.

I’m a scientific instrumentalist. While I generally think our scientific theories are telling us about reality, I think to “tell us about reality” is to be a useful prediction instrument. They are one and the same. There is no understanding of reality which is not such an instrument.

We can’t rule out idealism. We can only note that any feasible version of it has to meet all the predictive successes of physicalism. Once it does, it has to then justify any additional assumptions it makes. It’s not clear to me that we then have anything other than physicalism by another name, or perhaps a type of neutral monism that amounts to the same thing.

But maybe I’m missing something?

Take some drugs and find out how mental you become as a result of a physical substance. Physical inputs determine your mental state; food, water, light, social factors, environment, and even electromagnetic impulses change your mental state. And then there’s the internal physical circumstance of material elements, DNA, proteins, enzymes, polypeptides, etc…

Mental isn’t non-physical, it’s the apex of everything physical

LikeLiked by 3 people

I totally agree. But an idealist would say that drugs, food, water, etc, are just mental constructs. Of course, if the drug is a mental construct, then it’s one with all the same experential qualities of what we took to be the physical version. In other words, we can have the conscious experience of physically manipulating it despite it being a mental construct. Eventually we reach a point where we’re just arguing about terminology.

LikeLike

If I’ve got a plate of food in front of me and eat it then refuse to pay for the meal…I’ll be off to imaginary jail!

I think I’ll take physical reality seriously

LikeLiked by 2 people

Robert, this is such a good argument for physicality

LikeLiked by 1 person

That’s really not of substance. Whether the jail is imaginary or not, it sucks there. To posit that it is a construct of mind does not prevent it from being real in that you must deal with it. The idealist would suppose that the world you experience is the product of mind– holding that it could be some mind other than your own– but it doesn’t dispute that engaging with that world affects it or that engaging with it can influence what happens to you. That is, we know you can’t choose to simply stop imagining jail, so the threat is substantial regardless of the underlying ontology.

I don’t like idealism, but accurately representing it is important regardless of your stance.

LikeLike

If you don’t believe in reality then find the tallest building in your vicinity and jump off! Land on your head for all that that would matter. If you don’t then you believe in reality. Talk is cheap!

LikeLike

[Dang … I wrote a long, scintillating response, which I lost when I when to look up Eric Schwitzgebel’s blog. Here’s the gn;cr (gone now;can’t read)]

The problem with Hoffman’s theory is that it conflates any knowledge with perfect knowledge. Thus, incomplete knowledge of reality is no knowledge of reality.

Kant was right. You can’t get to fundamental knowledge (noumenon), but that doesn’t mean the knowledge you can get isn’t knowledge of reality.

There is an easier solution to the hard problem, but I’m not sure how unreliable introspection is it. Or is that a solution to the meta problem of why we think there is a hard problem. I think representation is a better solution to the hard problem, and Searle’s Phenomenological Illusion is a better solution to the meta problem.

Some (would be) philosophers (like myself) may tend to be dismissive of theories like Hoffman’s, but Eric Schwitzgebel’s recent paper, accessible from his blog post gives good reasons why we should consider such ideas seriously.

*

LikeLiked by 1 person

[Hate it when I lose a long comment. One of my wish list items for WordPress is a draft save for comments.]

Interesting point about Hoffman pursuing certainty. I’m not sure if I see that though. But I agree that absolute certitude will never be attainable and shouldn’t be the measure of knowledge. Knowledge is reduction of uncertainty, not elimination of it.

I do take Hoffman’s theory seriously. It’s why I posted on it, even though I think it’s wrong. The people I don’t take seriously, I rarely bother doing posts on.

Have you seen this Aeon piece on Charles Pierce that came out today? I know you’re interested in semiotics.

https://aeon.co/essays/charles-sanders-peirce-was-americas-greatest-thinker?utm_medium=feed&utm_source=atom-feed

LikeLike

[Go backpacking for two days and all kinds of things show up for my reading list. Unfortunately, I read really slow.]

So I just read the Peirce (pronounced “purse”) article. Have you? Think you are a pragmatist? (Seems close to how you describe an instrumentalist.)

*

LikeLike

[Reading slow usually leads to better comprehension.]

I did read it. I found the distinctions between the different signs: icons, indexes, and symbols, very interesting, particularly in relation to that bee study which asserted that bees understand symbols, but almost certainly just understand indexes. (A better name for “index” might have been “indicator”.)

Instrumentalism and pragmatism are definitely related. Some pragmatists though are a bit too flexible with the “useful” metric, categorizing entities as real when they are useful for things like emotional comfort. For an instrumentalist, it has to be useful epistemically, meaning it has to lead to more accurate predictions.

LikeLike

FWIW, I’m not convinced by the author’s distinction between index and symbol. One of the unfortunate things about Peirce’s work is his penchant for things coming in three’s. I get the feeling that he (and his fans) would bend over backwards to cram things into one of the categories, or else simply leave them out, instead of talking about something that is kinda in between. For example, he talks about interpretation, but only in terms of the outputs, never the mechanism. The mechanism can be abstracted away (multiply realizable, and all that), but it would still be a fourth component of a sign.

*

LikeLike

I do think the distinction is a productive one, but admittedly it’s a matter of degree, how separated is the sign from what it signifies. A relatively simpler index seems like something that can be learned operantly. It doesn’t seem to require the same complex mechanisms that full on symbolic thought requires, something that seems to be limited to a much smaller number of species, and apparently the recursive and hierarchical version that enables language, mathematics, etc,, at least at the moment, is unique to humans.

LikeLike

I think the distinction is more important than just calling what seems to be a symbol an index, and it’s not just a matter of degree. There are step changes. For example, there is the case where the sign vehicle (called the Form in the article) is just a result of a physical process (smoke -> fire), and there is the case where the sign vehicle is an arbitrary physical event (bell -> food), and there is the case where the sign vehicle is an arbitrary arrangement of physical things such that a different arrangement of those same things have a different meaning (“d”,”o”,”o”,”r” -> door, as opposed to odor).

Great, so now I’m not sure what makes a symbol a symbol. [gotta figure that out again. It can’t just be the requirement of “culture”]

BTW, Peirce may have addressed the situations described above. Apparently for every type of sign vehicle (icon, index,symbol) there are exactly three kinds of that sign vehicle. It gets complicated. See here for a quick taste if you’re feeling masochistic.

*

LikeLike

That’s always been my struggle when I tried to read about semiotics. There are so many terms, and their meanings are so ambiguous, that I get hopelessly lost. The Aeon piece says Peirce was much clearer in his definitions than other semioticians, but if so, everything I’ve tried to read describing them is mucking it up.

When you first mentioned semiotics, I tried reading this book, but even in graphical form I found it obfuscated.

Glancing through it, it seems like the distinction between an index and a symbol comes down to the firstness, secondness, and thirdness way of knowing, which the Aeon piece touches on. I’m not sure if I’m understanding, but firstness sounds like phenomenal qualities, secondness appears to be something modeled in the situation: “brute facts”, while thirdness is a universal. So smoke indicating fire is secondness, while the word “door” is thirdness, a universal.

That said, there’s so much about this I don’t understand that anything I say here should be taken with a pound of salt.

LikeLike

Finite beings that emerged from an infinite and eternal totality are never going to comprehend the totality. You’ve got your little cross section of time and space to account for and you can only do it from experience and knowledge. In the end you didn’t ask to be born and so the universe needed you for some reason…and no one has come up for a credible explanation yet 🎯

LikeLiked by 1 person

Well, we generate entropy, something the universe seems to like more of.

LikeLike

Even entropy is not understood, and in fact contradicted; It seems that there is a limit to entropy where order emerges from it in self organizing patterns.

If you take the Aristotelian view of an infinite and eternal universe then at best G-d is the Universe….Pantheism.

Modern physics has determined that the Quantum Vacuum itself is a feedback looping mechanism that informs everything organically; So the Universe is likely also self-aware and conscious.

Here’s my question for you; What is Eternal and Infinite and Conscoius? Could it be G-d? This means that G-d is not non-physical, but physical. It means that mind is not non-physical but physical. It also means that Spirituality is not non-physical but the elevation of the physical!

The Judaic concept of Monotheism is revolutionary but the meaning of the interpretation has been inverted from what is reasonably true. What is it that you know of that exists, but isn’t physical?

LikeLike

“Here’s my question for you; What is Eternal and Infinite and Conscoius?”

My answer is nothing, but I’m not a believer.

“What is it that you know of that exists, but isn’t physical?”

Consider that we only ever have access to our own subjective experience. We never have access to anything else. Ever. So whatever you take to be physical are theoretical objects that it seems predictive to assume are independent of your consciousness, that is, are what we typically label “physical.” Whatever the “ultimate” reality, the fact is that this model works extremely well, but at the end of the day, it is a model.

LikeLike

Your confusing the symbology for the reality; The universe is not in your head, and not a product…the mind is the product.

I have no reason to doubt the food I eat is real. I have reason to doubt the person telling me it’s not real.

LikeLike

I agree with your ontology, although not with your certitude on it.

LikeLike

The source of the confusion as always Western Religion; It submits and autonomous G-d and Semi-Autonomous people where it’s obvious that neither assertion is true. G-d is constrained and so are people.

Eastern Philosophies and Religions worship Nature as G-d and understand the limits within this context.

There are only two academically acceptable forms of argument; Mathematics and Linguistics and both are parallel symbology’s to reality. Computers can handle both symbology’s processing them faster, and remembering them exactly. Does this make computers non physical because they can out think us? There is no non physical, it’s a creation of Western Theism that is non rational and blurts reality from fantasy and provides FAITH as the answer. Faith is playing the game of “ Make Believe!”

LikeLike

“Kant was right. You can’t get to fundamental knowledge (noumena), but that doesn’t mean the knowledge you can get isn’t knowledge of reality.”

I disagree with Kant, and here’s a quote I find useful in Schwitzgebel’s “Kant Meet Cyberpunk”.

“…whatever we know about external things, apart from what is knowable a priori or transcendentally, appears to depend on how those external things affect our senses. But things with very different underlying properties, call them A-type properties versus B-type properties, could conceivably affect our senses in identical ways. If so, we might have no good reason to suppose that they do have A-type properties rather than B-type properties. Maybe if A-type properties are much simpler than B-type properties, and if we have reason to suppose that the underlying reality is relatively simple, then we can infer A-type rather than B-type properties.”

A-type properties would be representative of noumena and B-type properties would be representative of phenomena. Even though Eric wrote the above as an anecdote to his essay, he does not take the idea seriously, which is really too bad; because that idea of and by itself is revolutionary.

LikeLiked by 3 people

Sounds like Eric put out an interesting paper. I’m starting to wish I’d had a chance to read it before composing this post.

LikeLike

As I was driving home last night it struck me how little we actually see, compared with how much we think we see. Anything we can see through (windscreen, air) we can’t see. Anything we can see, we can’t see through, so we don’t see anything beyond it. So what we actually see is the thin shell made up of the surface of the first opaque object our vision falls upon.

Obvious I know, but it does make you realise how much (probably!) exists that we never sense.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Definitely. I think physicalism is a productive model of the world, but ultimately it pays to remember that it’s just a theory (or meta-theory). We can only sense what we can sense, and build whatever models we can based on that.

LikeLike

“This too is a sharp distinction between the manifest image and the scientific view. The problem, of course, it’s that this version isn’t emotionally comforting.”

I think part of what you are missing is that the scientific view is part of the manifest image. It is not separate. Neurons, DNA, evolution, brains, physics, space-time – it’s all part of the human manifest view.

“Per the hard problem, there’s no way to relate physics to consciousness, so maybe the solution is to do away with all physics.”

Not so much to do away with physics but instead derive it from consciousness.

LikeLiked by 2 people

“I think part of what you are missing is that the scientific view is part of the manifest image.”

I did actually note in the post that the manifest image is itself just a theory of reality at a certain level of organization, just the one we evolved to directly perceive.

“Not so much to do away with physics but instead derive it from consciousness.”

Right. But isn’t that what we already do? We only ever have access to our own subjective experience, our own consciousness. Everything else is a model, a theory. As I noted in the post, in the end, we can only judge those theories by how well they predict future subjective experiences. We call the entities in these models “physical” because they conform to predictable patterns.

So the question is, what additional derivation do we think will be available?

LikeLike

There can’t be a sharp distinction between the manifest image and the scientific view if the manifest image contains the scientific view. Your whole post is predicated on the idea these are opposing or contrasting views.

There isn’t anything emotionally comforting about the idea that we live in something like the Matrix.

“We only ever have access to our own subjective experience, our own consciousness. Everything else is a model, a theory.”

Hoffman’s view is that our consciousness itself is a model, a theory. There isn’t a distinction.

Hoffman is trying to derive space-time from interacting conscious agents. In that case, its origin would be in an evolutionary fitness function.

LikeLike

“Your whole post is predicated on the idea these are opposing or contrasting views.”

There’s more nuance than you’re giving me credit for. Strawmanning the position of others doesn’t leave much room for productive philosophical discussion.

“There isn’t anything emotionally comforting about the idea that we live in something like the Matrix.”

The comfort is that we (conscious entities) are back at the center of things, instead of the miniscule role we play in the universe as seen by physics. I suspect many would prefer a Matrix scenario to irrelevance.

“Hoffman’s view is that our consciousness itself is a model, a theory. There isn’t a distinction.”

I agree with him on that. But as a theory it’s just as fallible as any of the others. One of my issues with idealism is that it doubts everything but other minds and our own introspection. I’ve never heard good arguments why those deserve exceptions, but without the first we have solipsism, and without the second we don’t have much left.

“Hoffman is trying to derive space-time from interacting conscious agents. In that case, its origin would be in an evolutionary fitness function.”

It would definitely be something if he succeeded in producing such a theory.

LikeLike

I don’t see a lot of nuance in your post. Here are some selected quotes:

“The manifest image can be contrasted with the scientific image of the world. ”

“The scientific image is often radically different from the manifest image”

“But if the manifest image of the world is how it appears to us, how do we develop the scientific ones? ”

“We take electrons to exist because they’re crucial to many theories. But they’re most definitely not part of the manifest image.”

Yes, electrons are part of the manifest image if you are following Hoffman’s argument. I think you are setting up a straw man position and calling it Hoffman’s.

It seems like you are fine with the idea that our subjective consciousness misrepresents or distorts reality but think you can escape the problem and get at the real reality by testing predictions.

Living in a Matrix doesn’t put us in the center of things. It just makes one type of conscious agent in a world of other conscious agents with different manifest images of the world.

LikeLike

“It seems like you are fine with the idea that our subjective consciousness misrepresents or distorts reality but think you can escape the problem and get at the real reality by testing predictions.”

Actually, my position is that we never escape it. All we ever get are our perceptions and the models we build with them, and the only way we can ever assess them is by seeing how accurate their predictions are. I’m skeptical of anyone who thinks they have any other way to know reality, including the contents of our own minds. That’s why I finished up by saying we can’t rule out idealism, but that any robust version of it is going to be hard to distinguish from physicalism.

LikeLike

You aren’t missing anything.

The reason to reject solipsism or idealism (and let’s face it, these are just the least subtle realist schemes) is that they allow no prediction.

If our situation is one in which we experience shadows on the cave wall, then things must simply look just as they do. Plato’s analogy breaks down when we critically imagine what will happen when we turn around.

We will confront either the flat, blinding light of Reality or more shadow-play.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Good point. One definition of the physical is that it’s predictable. If we cast that aside, then we’re just left with amorphous descriptions that can’t be tested or useful.

LikeLike

i used to tell my students that learning science was training our minds to think in the patterns of nature. Philosophers seem to compound how we perceive the universe with the universe itself. They are only perceptions. They don’t mean anything to the material universe.

When we look in the mirror in the morning what do we see? We might see a son, or a father, or a husband, or an employee. Well, which is it? What we see says a lot about our thoughts and very little about reality.

What we see is a matter of choice and education. When I see the fall colors of the trees in this neck of the woods I see pretty colors. I happen to know what the chemicals and process are behind those colors and the changes that occur at that time of year, so I see those also. (“We see what we want to see and disregard the rest.” Paul Simon Lyric) What does what I see say about Nature? Nothing. It says a lot about me, however.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Good point. A lot of what we perceive are cultural artifacts. And when we work to be more primal in considering what we’re seeing, we see affordances, evolutionary artifacts that we’re programmed to see because seeing them is adaptive.

And it’s not like we can decouple our perception from these things. They are part and parcel of perception. All observation is unavoidably theory laden.

LikeLike

I agree with James Cross that there really isn’t much distinction between the “manifest” view and the “scientific” one. It’s just the distinction between our easily fooled senses and our much less easily fooled instruments. The scientific view is simply more accurate, more precise, that’s all.

Genuine idealism (as you defined it, and I agree) seems wrong to me. If it were true, I’d expect reality to be a lot more malleable than it seems to be. I think the scientific age, and our instruments, pretty much killed idealism as a viable approach.

Idealism requires that we imagine a very consistent, very complex, very large reality (with amazing sub-atomic level detail). Halley’s Comet is always right where we think it is. Electronic circuits always function like they should. Chemistry always works.

I don’t attach much weight to how our senses give us a high-level, sometimes inaccurate, view of reality. I don’t perceive atoms because I have no need to perceive atoms. Doing so would complicate things enormously. Earth’s biology evolved to interact with reality on a useful level, that’s all.

Our crude senses do not imply reality isn’t real. Our instruments have clarified that view, and either reality is really real, or our idealism is so consistent as to amount to the same thing.

That said…

I just finished Greg Egan’s Quarantine, in which human consciousness really does collapse the wave-function (due to specific neural pathways). Everything else exists as a superposition of possibilities. Human minds create reality by selecting which branch to collapse on.

The question about idealism is: What about before human minds? (And what about things far outside our influence?) In Egan’s story, that question is significant to the plot (so I won’t spoil it), but in the real world, if idealism is true, then we’re pretty awesome world-builders. God level!

LikeLiked by 2 people

“Idealism requires that we imagine a very consistent, very complex, very large reality..”

As opposed to an inconsistent, simple, small reality that you would expect?

LikeLike

Pretty much. If humans really brought reality into existence based on their ideas, I’d expect reality to be a lot more like a Max Fleischer cartoon.

LikeLike

(Or George Herriman!)

LikeLike

But it makes perfect sense, I guess, that a very consistent, very complex, very large reality would assemble itself randomly?

Optical illusions provide insight into how much perception creates the world.

LikeLike

“But it makes perfect sense, I guess, that a very consistent, very complex, very large reality would assemble itself randomly?”

Certainly more than that it’s all in our heads. Just consider how, on just about any topic, humans are divided in their perceptions and opinions. If that spread of thought affected reality, it would necessarily be a lot more chaotic and less lawful than it is.

Physical reality (currently) requires the Big Bang and the laws of physics (and abiogenesis) as axioms, and there are some unknowns (like DM and DE), but otherwise everything is consistent and well explained by the laws of physics.

“Optical illusions provide insight into how much perception creates the world.”

So, when I look at an Escher print, I create that reality?

No, optical illusions just show how our sensory equipment can be fooled. The visual processing we do is really quite an amazing trick given what it does, so it’s not surprising it can be fooled.

Consider that most optical illusions require specific engineering, and in many cases require 2D representation, so they are not generally something our visual systems have evolved to handle. (Nor have they needed to handle it, as clearly demonstrated by the success of the human race.)

Thinking something is real doesn’t make it real (except to you) and isn’t what I think of as idealism. My understanding of it is that it contrasts with realism in asserting that the primary grounding of existence comes from our mental states. Realism asserts our mental states are grounded in a reality that is “really out there.”

LikeLike

Who said it’s all in our heads? I didn’t.

LikeLike

Well, then it appears we’re on the same page, so why are you questioning me?

LikeLike

“So, when I look at an Escher print, I create that reality?”

Actually yes. You are seeing it, right?

LikeLike

“So, when I look at an Escher print, I create that reality?”

Even if you take a completely physicalist perspective, if you are seeing anything more than black lines on a white background, it is completely you creating that reality.

LikeLike

That’s not at all what I consider to be idealism. The “reality” in my mind comes from the primary reality of the print.

LikeLike

My point wasn’t about idealism which is why I prefaced it with “Even if you take a completely physicalist perspective”.

It was how your perceptual apparatus forms a reality from something that is actually quite different from it. The print is flat and consisting of black lines on white background. Yet you can “see” an impossible waterfall. It works because the artist is using the same visual tricks to create the image that you use to reconstruct it. The shadings provide a sense of three dimensionality and depth but distorted proportions provide an illusion of seeing something that cannot happen in nature.

This may be fooling your sensory equipment but, if the proportions had been correct and the waterfall were possible, it would still be “fooling” your sensory system. This is how the sensory system works and why we are not likely “seeing” reality.

LikeLike

“It was how your perceptual apparatus forms a reality from something that is actually quite different from it.”

Well, yes. I’ve agreed with that from the start and several times since. Why would it be a point you’re trying to make? We’re discussing idealism (at least I am — I’ve always been quite clear about our internal model of reality).

LikeLike

Keep in mind that our senses and brain routinely assemble a representation of this very consistent, very complex, very large reality. This is what we do every waking moment.

LikeLike

Of course. Consciousness is all about our internal model of reality. Kant was right about that. But that doesn’t, in any way, speak to reality not being real.

LikeLike

Who says reality isn’t real? I didn’t.

LikeLike

The idea of a manifest image, at least as I understand it, isn’t a precise thing. It’s just the world as it naively appears to us. As I noted in the post, it is itself a theory of the world, often a very predictive one. But at other levels of organization it starts to become inadequate. But there isn’t a sharp distinction. As I also noted, a lot of science works within the manifest image.

“Our instruments have clarified that view, and either reality is really real, or our idealism is so consistent as to amount to the same thing.”

I think this is basically right, but it’s worth mentioning that an idealist would likely say there are no instruments, just mental concepts we take to be instruments, and so their clarifications can’t be trusted. This also comes into how much we can trust our own memories. Most classic idealist scenarios leave the mind untouched, but if we start talking about newer ones like simulation hypotheses, all bets are off.

Egan’s story sounds interesting. I didn’t know he’d gone there.

The question of before humans in idealism is interesting. It seems to depend on the specific variant. I suspect the classic versions would say there is no before. The newer ones, that posit consciousness everywhere, blending somewhat with panpsychism, might allow for it, although at some point we get back to it being the same thing, and you really have to wonder what we mean by “physical” and “mental”.

LikeLike

This isn’t really a debate about whether reality is real or illusion. Reality is real in idealism too. It is a issue about the underlying nature of reality. If it turns out to be mind, that doesn’t mean reality is an illusion. An illusion would be a mistaken perception of the world.

I think you can understand Hoffman in two steps.

Step one is related to his evolutionary games and theories of perception. His theory involves three things:

1- The world (assume physical for the moment)

2- An organism’s perception of the world

3- Action on the world arising from decisions based on the perception

He draws this as a triangle with world -> perception -> action -> world

His theory is that our perceptions guide our actions on the world and result in either survival or death. Perceptions that result in actions that enhance survival are favored over veridical perceptions. Of course, perceptions that enhance survival are likely to be more predictive within the range of organism’s niche but that doesn’t mean they are more true to reality. He gives the example of the male jewel beetle that used a particular shade of amber to determine females to mate with. Very predictive for thousands of years but a complete failure when people began tossing beer bottles that happened to be the same shade into the bush.

This is all expressed mathematically and in the simulations.

Step two. You replace the world with other conscious entities that can take actions.

The games work the same. The world of conscious entities works in the equations the same as the physical world.

LikeLike

I think the actual distinction is whether there are things that exist independent of minds. The problem is that we only ever have access to our own consciousness. Everything we think we know are mental models. Still, ignoring those models seems to come with consequences, often painful ones.

I think your final point is the one that I always work my way around to when pondering this. We have our conscious perceptions, we infer and predict entities, predictions which seem to be accurate and useful, at least for our own purposes. If the ultimate reality is something utterly different from that, it doesn’t change our manifest reality, even if the manifest one is caused or emerges from the deeper one.

The question is if this ultimate reality impinges on our perceptions and models in any way. In other words, is there any way to test it? Does it being true or false make a difference in our perceptions? Mathematics and simulations, by themselves, are just more theory.

LikeLike

“I think the actual distinction is whether there are things that exist independent of minds.”

Both Kastrup, Hoffman, and me think there is something independent from our minds. For Kastrup it is a mind at large. For Hoffman it is a network of conscious agents (maybe a mind at large by another name). For me I would rather think of the world outside my mind and my mind as existing in a continuous field with my mind able to control parts of it. We can think of the field as mind or matter, which probably places me more in the category of neutral monism.

Whether this leads to any new science or predictions I’m not sure. Certainly Hoffman’s attempts to derive space-time from a network of conscious agents wouldn’t be in conflict with either idealism or neutral monism. It would certainly suggest that objective world is formed either entirely by consciousness or through significant interaction between consciousness and something else, maybe forever to be unknowable.

LikeLiked by 1 person

“If the ultimate reality is something utterly different from that, it doesn’t change our manifest reality, even if the manifest one is caused or emerges from the deeper one.”

The only thing that changes is the knowledge that both materialism and idealism are false. That in itself is huge, a revelation which could reshape culture as we know it.

“The question is if this ultimate reality impinges on our perceptions and models in any way.”

The ultimate reality does not just impinge on our perceptions, it’s centric to causation, which means it is centric to who and what we are as conscious discrete systems. In other words, it is the driving force of causation which results in the novelty of motion and form, a model which supersedes the need for this notion called law.

“In other words, is there any way to test it?”

Absolutely! It’s called scientific observations reinforced by the empirical evidence of personal experience. We already possess the overwhelming, indisputable evidence, all one has to do is jettison materialism and idealism as the reference point and re-examine the evidence in a new light. Here’s the overwhelming obstacle to the re-examination of that evidence: this new understanding will not result in more control, in fact, it actually highlights how little control we actually have. In a paradigm predicated upon control, neither materialists nor idealists will be happy with the true nature of reality because there is no promise of salvation at the end of that tunnel. That’s the bad news.

Materialism cannot account for mind, and idealism cannot account for the why of materialism. A model grounded in transcendental idealism revision 1.0 can account for both. Materialism is the venue for mind, and mind which is underwritten by materialism is a condition on the possibility of reality. That’s the good news, good luck…

LikeLike

“The only thing that changes is the knowledge that both materialism and idealism are false.”

But what does it mean to say that? What changes about, say, an apple in a neutral monistic view of the world? Or of my mental conception of the apple?

“We already possess the overwhelming, indisputable evidence, all one has to do is jettison materialism and idealism as the reference point and re-examine the evidence in a new light.”

Some examples here might be helpful. Again, what new insights do we get into an apple, a dog, a chair, or a feeling of ennui?

LikeLike

What it means Mike, is that we won’t be debating non-sensical things like: “What changes about, say, an apple in a neutral monistic view of the world? Or of my mental conception of the apple?” Or: “what new insights do we get into an apple, a dog, a chair, or a feeling of ennui?”

That what it means. Examples? For one, we just might, and I use might with trepidation. We just might focus our collective energies and resources into decreasing the prison populations for one, most of which are minorities in prison for drug related charges. We won’t be as engaged in religious, ethical, and ideological tribalism for number two. We might even see each other in the same light and actually have a desire to treat and respect each other with dignity, empathy and compassion. Any other questions?

LikeLike

“As I also noted, a lot of science works within the manifest image.”

It’s like I was saying recently about the QFT-GR problem in the virtual reality hypothesis: Most of the model’s behavior just doesn’t need that low-level quantum calculation. But in a few places it does have to account for small-scale behavior.

“…an idealist would likely say there are no instruments, just mental concepts we take to be instruments…”

The main point still applies, though. The world that is revealed via those is too consistent and too complex — I would say it’s beyond our imagination. How often have you pointed out how reality isn’t intuitive? Every one of those situations argues against idealism.

That we can build predictive models at all speaks to there being a lawful physical reality.

“The newer ones, that posit consciousness everywhere, blending somewhat with panpsychism,…”

I like to keep in mind the assertion that while it’s wise to keep an open mind, it shouldn’t be so open one’s brains fall out. Idealism and panpsychism are a bit too open-minded, in my book. 😀

When I was in high school I had an idealist theory that we shaped reality. Our growing knowledge about things just reflected deeper thought on our part. Or reflected thoughts we’d never bothered to have before.

My canonical example back then was the discovery of the benzene ring though August Kekulé’s dream of a snake eating its own tail. Per my theory, that dream created the benzene ring for Kekulé to then find.

But (A) it’s not certain the snake story is even true, and (B) it ignores the majority of cases where science involves (seemingly) genuine discovery or serendipity. I gave up that hypothesis in college as I got more into science and philosophy.

LikeLike

“I like to keep in mind the assertion that while it’s wise to keep an open mind, it shouldn’t be so open one’s brains fall out.”

I think it is an important habit to periodically put on a different perspective, to inhabit it, try it on, even if only temporarily. It’s why I say if I were troubled by the hard problem I’d probably be attracted to panpsychism, or even that naturalistic panpsychism isn’t necessarily wrong, even if I don’t find it particularly productive.

In the case of idealism vs physicalism, I think once we admit that we only ever have access to our own consciousness, it makes idealism difficult to rule out completely. But as I noted in the post, a rigorous version of it, seems like it would be instrumentally very similar, if not identical, to physicalism.

Maybe once we agree on monism, and to stick to models that are predictive, the only real difference is in which label we prefer.

LikeLike

“I think it is an important habit to periodically put on a different perspective,”

Of course! I’ve no objection to the exploration. I’m just saying I can’t take certain conclusions very seriously. (And, of course, as ever, just my take on it.)

“In the case of idealism vs physicalism, I think once we admit that we only ever have access to our own consciousness, it makes idealism difficult to rule out completely.”

I see that line of thinking as essentially solipsistic.

Very early in the thinking of any new consciousness there is a key decision to be made regarding a theory of other minds. Do you accept them as real, as like you, or not?

It’s not really possible to disprove solipsism, but accepting it leads nowhere (and seems incredibly egocentric, to boot). Accepting the existence of other minds argues against idealism to me. It’s still possible all 7+ billion of us conspire to create reality, but I can’t see it as anything but science fiction.

“Maybe once we agree on monism,…”

In many regards, that has always been the fundamental question.

LikeLike

“I see that line of thinking as essentially solipsistic.”

Of course, solipsism can’t be ruled out, but as you note, it doesn’t lead anywhere. So then we decide there’s something other than our own mind. If we doubt the physical world, then that leaves only other minds. A question that always arises for me with idealism, why doubt physics but not other minds? Why not doubt other minds but keep physics? Maybe all but one of us is a zombie. Or maybe most of us are except for a small number of actually conscious individuals.

It always seems to come back to us having experiences and building models to predict future experiences. For me, it seems reasonable to call the models that make accurate predictions “real”. Although that realness may be emergent on top of other underlying realities.

Is that underlying reality necessarily a collection of minds interacting with each other? Perhaps, but that seems like an infinitesimal slice of the possibilities. In the history of science, our track record of guessing which infinitesimal slice is the right one is very poor. If there is an underlying reality utterly different from our scientific models, it’s more likely to be an alien landscape no one has yet imagined.

LikeLike

“Or maybe most of us are except for a small number of actually conscious individuals.”

I’ve played with that idea, too, but I tend to think of it as more a good science fiction idea. For me accepting the idea of other minds having parity with mine includes accepting realism.

(FWIW, I contrast idealism with realism; the latter including monism, dualism, and any view that sees external reality as primary.)

“For me, it seems reasonable to call the models that make accurate predictions ‘real’. Although that realness may be emergent on top of other underlying realities.”

True. Epicycles, for example, had predictive power. For that matter, so did Newton until we got to the precession of Mercury’s orbit. (And Einstein doesn’t predict what happens in singularities — the search continues!)

LikeLike

“FWIW, I contrast idealism with realism; the latter including monism, dualism, and any view that sees external reality as primary.”

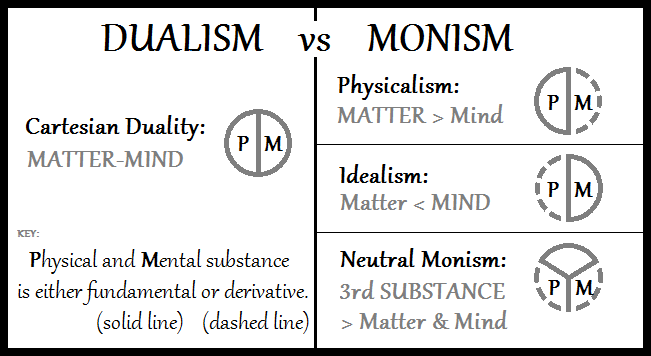

Idealism is usually considered a type of monism, just with everything being mental instead of everything being physical. The Wikipedia on dualism has this chart.

I mentioned neutral monism in the post, but it appears to have ontological commitments, so maybe I should have said “agnostic monism”.

LikeLike

In my hierarchy, I place the idealism-realism divide as higher than those others. To me one of the very first questions involves solipsism. Once one decides that, yes, reality is real, then one can begin to ask questions about its nature.

LikeLike

So you reject any distinction between solipsism and idealism, even in principle? As I noted above, I do have trouble seeing why we should exempt minds if we’re going to be skeptical of the external world, but I accept that people do make the exemption, and that the views are distinct.

LikeLike

I find them equally worth rejecting, but do distinguish that solipsism is solitary while idealism isn’t. Solipsism is thus a type of idealism.

LikeLiked by 1 person

As an ontology, idealism has always been hamstrung by the “why” of physicalism. The how of physicalism was an easy obstacle to overcome, consciousness simply creates it. Hoffman’s interface theory is a notable attempt at trying to account for the why. Hoffman’s answer: There needs to be an interface through which conscious entities can communicate and share ideas. Brilliant!

I do have a question though: If consciousness is the omnipotent ontological primitive that idealists tout it to be, why does consciousness need to resort to the “gadgetry” of a physical world in order to communicate and share ideas with itself? Just thinking out loud here…

LikeLiked by 2 people

“why does consciousness need to resort to the “gadgetry” of a physical world in order to communicate and share ideas with itself? ”

I think that’s an excellent question. If it’s all just conscious minds, why all the complexity in interacting? Why do I have to exert effort (even if just mental effort) when I’m “far away” from someone to “get nearer” to them so we can interact? Am I really just needing to get in the right mood?

And if there is no reason for all this busywork, but it’s consistent and unavoidable, then how are we not just describing physics with different terminology?

LikeLiked by 1 person

On a more serious note, I did isolate a very intuitive insight Hoffman expressed in the Michael Shermer podcast. That would be material reductionist theory itself. Reductionism has run its course and reached an impasse. What is needed now are theories grounded in metaphysics. Quantifiable metaphysical hypotheses which will accommodate all of the science we established so far including but not limited to general relativity itself.

LikeLiked by 1 person

It seems like every scientific theory actually is a metaphysical proposition. Due to the problem of induction, we can never know for sure that a rule or pattern we detect in nature holds in every occurrence. All swans are white, until we see a black one.

LikeLike

The interface isn’t for conscious entities to share and communicate. It is what provides a view of the world to guide actions that enhance survival chances.

LikeLike

I disagree. To quote a famous philosopher, it all adds up to normality.

Brane theory and Everettian QM are promising precisely because they predict our experiences. Most definitely including most of our manifest image. There’s really a difference between solids and gases, and QM can explain it, not explain it away.

Mathematical universe hypothesis doesn’t particularly predict our experience over any other result, so I won’t say it adds up to normality. I regard it the way Freud’s severest critics regard his theory: it can explain anything, so it explains nothing.

LikeLiked by 1 person

The famous philosopher being Greg Egan, in Quarantine. I swear I didn’t read Wyrd Smythe’s comment before posting the above. I didn’t even know that Egan was the original source until I looked it up.

LikeLike

Those theories were just presented as examples of other views of radically different ontology. I didn’t mean to imply anything about their merits.

LikeLike

I didn’t really want to get into their merits, either. But I felt I had to explain why I left off Mathematical Universe from the list of what “adds up to normality”. Sorry for the digression. I need to add more “BTW, in case you wondered…” or whatever type warnings when I do that.

LikeLike

No worries. Discussions evolve and I’m open to that. And I agree that every scientific theory, if it is a scientific theory, eventually has to get back to the world as we perceive it.

I can definitely see the argument that the MUH is just metaphysics. Max Tegmark asserts that it is a scientific theory, but as far as I can tell, the only way it could be tested is if the final theory of everything (if there is such a beast) ends up being a purely mathematical one.

And, of course, a lot of people assert that brane theory and many worlds are metaphysics too, although they seem less further beyond empirical reach.

LikeLike

Actually I think Egan says the book is based on mistaken ideas about QM. It was fiction so I can forgive that but I wouldn’t try to use it as basis for anything else.

LikeLike

You made me curious. At this link, Egan discusses the premise of Quarantine, and you’re right, it’s a deconstruction of it.

http://www.gregegan.net/QUARANTINE/QM/QM.html

LikeLike

Yes, the book dates back to 1992 and Egan mentions: “I’ve often looked back and winced at some scientific flaws in the novel that go beyond the mere implausibility of its central premise.”

But it’s still quite entertaining. I was thinking of doing a post on it, but I’m feeling really lazy today.

LikeLike

I’m looking forward to that post. From what I read, it’s an interesting novel.

LikeLike

I liked it. Working on the post now.

LikeLiked by 1 person

(FWIW, not mistaken ideas about QM itself but about a particular application of its rules.)

LikeLike

Even in fiction, true things are sometimes said. Sometimes profoundly true things. (Not that interpretation of QM, just the line “it all adds up to normality”.)

LikeLiked by 1 person

Maybe it’s just me, but I took that, at least in part, as a reference to how quantum probabilities must always sum to 1.00. But it is quite possible that was just my interpretation of the line (which is repeated many times in the novel). (Which I just read! 🙂 )

LikeLike

Language is the mind. We’re are language essentially. If language is non representational then it suggest all that we say and write does not relate to the physical world but to the linguistic domain. They’re is a a linguistic paradox here.

#itslanguagestupid

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Michael,

I think language is a big part of human mentality. Arguably, it, more specifically symbolic thought, of which language is just the “killer app”, is what separates us from other conscious animals. It’s the distinction between the rational soul and the sensitive soul, between human level consciousness and more primal forms.

That said, a human may suffer injury or pathology to Wernicke’s area in their brain and lose the ability to understand language, but arguably they still have a mind, just a diminished one.

LikeLike