One of the current debates in consciousness research is whether phenomenal consciousness is something separate and apart from access consciousness. Access consciousness (A-consciousness) is generally defined as perceptions being accessible for reasoning, action decisions, and communication. Phenomenal consciousness (P-consciousness) is seen as raw experience, the “something it is like” aspect of consciousness.

Most researchers accept the conceptual distinction between A-consciousness and P-consciousness. But for someone in the cognitive-theories camp (global workspace theory, higher order thought, etc), P-consciousness and A-consciousness are actually the same thing. P-consciousness is a construction of A-consciousness. Put another way, P-consciousness is A-consciousness from the inside.

However, another camp, lead largely by Ned Block, the philosopher who originally made the A-consciousness / P-consciousness distinction, argues that they are separate ontological things or processes. The principle argument for this separate existence is the idea that P-consciousness “overflows” A-consciousness, that is, that we have conscious experiences that we don’t have cognitive access to, perceptions that we can’t report on.

Block cites studies where test subjects are briefly shown a dozen letters in three rows of four, but can usually only remember a few of them (typically four) afterward. However, if the subjects are cued on which row to report on immediately after the image disappears, they can usually report on the four letters of that row successfully.

Block’s interpretation of these results is that the subject is phenomenally conscious of all twelve letters, but can only cognitively access a few for reporting purposes. He admits that other interpretations are possible. The subjects may be retrieving information from nonconscious or preconscious content.

However, he notes that subjects typically have the impression that they were conscious of the full field. Interpretations from other researchers are that the subjects are conscious of either only partial fragments of the field, or are only conscious of the generic existence of the field (the “gist” of it). Block’s response is that the subjects impression is that they are conscious of the full thing, and that in the absence of contradicting evidence, we should accept their conclusion.

Here we come to the subject of a new paper in Mind & Language: Is the phenomenological overflow argument really supported by subjective reports? (Warning: paywall.) The authors set out to test Block’s assertion that subjects do actually think they’re conscious of the whole field in full detail. They start out by following the citation trail for Block’s assertion, and discover that it’s ultimately based on anecdotal reports, intuition, and a little bit of experimental work from the early 20th century, when methodologies weren’t yet as rigorous. (For example, the experimenters in some of these early studies included themselves as test subjects.)

So they decided to actually test the proposition with experiments very similar to the ones Block cited, but with the addition of asking the subjects afterward about their subjective impressions. Some subjects (< 20%) did say they saw all the letters in detail and could identify them, but most didn’t. Some reported (12-14%) believe they saw some of the letters along the lines of the partial fragmentary interpretation. But most believed they saw all the letters but not in detail, or most of the letters, supporting the generic interpretation.

All of which is to say, this study largely contradicts Block’s assertion that most people believe they are conscious of the full field in all detail, and undercuts his chief argument for preferring his interpretation over the others.

In other words, these results are good for cognitive theories of consciousness (global workspace, higher order thought, etc) and not so good for non-cognitive ones (local recurrent theory, etc). Of course, as usual, it’s not a knockout blow against non-cognitive theories. There remains enough interpretation space for them to live on. And I’m sure the proponents of those theories will be examining the methodology of this study to see if there are any flaws.

Myself, I think the idea that P-consciousness is separate from A-consciousness is just a recent manifestation of a longstanding and stubborn point of confusion in consciousness studies, the tendency to view the whole as separate from its components. Another instance is Chalmers himself making a distinction between the “easy problems” of consciousness, which match up to what is currently associated with A-consciousness, and the “hard problem” of consciousness, which is about P-consciousness.

But like any hard problem, the solution is to break it down into manageable chunks. When we do, we find the easy problems. A-consciousness is an objectively reducible description of P-consciousness. P-consciousness is a subjectively irreducible description of A-consciousness. Each easy problem that is solved chips away at the hard problem, but because it’s all blended together in our subjective experience, that’s very hard to see intuitively.

Unless of course I’m missing something?

h/t Richard Brown

I think I’d want to see a highly mature field of neuro-psychology before I’d try to decide whether Ned Block was onto something. It think it depends on the gory details of how self-awareness works. If there is really *one* global workspace where all multi-sensory integration happens, and subjects’ reports are drawn from there, then access and phenomenology are just outside and inside views of the same thing.

LikeLiked by 2 people

It would be interesting if there are multiple workspaces. Would the ones other than the one we report from amount to subterranean consciousnesses? I sometimes think a case could be made for one in the midbrain, although it would be pretty limited.

LikeLike

Much of this, for me, is like math and baseball for you, but I was struck by:

And it certainly seems they are different aspects of the same organism, perhaps a little like how some trees and animals have winter and summer aspects?

Our minds seem to have many modes or levels of cognition. I think what we can access is just rises to the highest levels of that cognition. Focus is a big part of that.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hmmm. This one didn’t have any neuroscience weeds. Or is it the research in general you find eye glazing?

Definitely focus, or attention, is a big part of it. Consciousness and attention can, in principle, be separated in experiments, but in normal circumstances they are closely related. And a lot happens outside of that focus, some of which can unexpectedly show up at times in conscious deliberation.

LikeLike

I think it’s a bunch of things. There’s the “three blind men and an elephant” aspect, which has led to a completing theories aspect I find tiresome. It’s all because we really don’t understand brains, yet. I think with both theoretical physics and with consciousness I’m reacting to what I perceive as being too certain about ideas that are speculation. Too much “is” and not enough “maybe” for my taste.

“And a lot happens outside of that focus,”

Yes, and I don’t find that at all surprising in something as complex and layered as consciousness.

I don’t think anyone will find mechanisms we can label “A” and “P”. I think those are modes — ways a whole brain can act.

LikeLike

I do think substantial progress is being made. This study represents a step in that progress, albeit an incremental one. But I can see how looking at each of these incremental moves in isolation might make the whole thing seem pointless. And I probably didn’t help matters by painting the whole P-consciousness / A-consciousness objective distinction as confusion, but I do think empirical investigation is needed to convince people of it. (Or convince me if I’m wrong.)

I don’t even think A and P are modes. I think they’re two sides of the same coin. But that’s me speaking as a functionalist and cognitivist.

LikeLike

Not pointless, but I think I’m to a point of “Spare me the labor pains, show me a baby.” I’ve been seeing the same points debated for many years now. Decades even. I just don’t find these incremental steps as interesting as someone more focused on the topic.

I’m tired of watching the band jam on this tune; bring it home already! 😀

Two sides of the same coin; I think we’re saying the same thing. One could say the same of winter/summer modes of some living things; two sides of a coin. There’s no localized subsystem responsible for hibernation in a bear or tree. It’s just an aspect of their biochemistry, of how their bodies work.

LikeLike

The problem is I fear bringing it home won’t be one event. I think it’s going to be like understanding biological life. Biologists once thought there would be some one thing or quality out there that separates life from non-life. We now know there’s no fine line separating the two. The “bring home” answer there is a lot of hideously complicated organic chemistry and system level organization.

I think the same will be true for consciousness. There won’t be one final answer. It’s just not that kind of problem. Instead, it will be composed of a lot of tedious details most people won’t want to bother with.

LikeLiked by 1 person

“Never mind the Block-heads, here’s the Sex Pistols”.—Damn, I wish I could find the link to their last show in San Francisco.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Sex does seem better than blocks.

LikeLike

Depends on the blocks. And the sex. 😉

LikeLiked by 1 person

I think the main problem is that people associate consciousness only with the system in our brain that can report it, such that consciousness (as correctly understood, eg., by me, ahem) which is associated with a different system in the brain just doesn’t count as “real” consciousness. For example, when we’re driving “on automatic”, thinking hard about some topic so not paying attention to the road, we say our experience of the road is unconscious, even though the experience has every element we would otherwise associate with consciousness. This still gives you P-consciousness being the first person aspect of A-consciousness. It’s just that there may be a different system that has A(ccess).

*

LikeLiked by 1 person

That’s one of the issues with discussing consciousness, it means different things at different times. It can mean awake and adaptively responsive to the environment, which the driving part of us is doing while we’re daydreaming. Or it can mean our direct first person experience, which includes the aspect we can self report.

The two seem to fuse when a novel situation comes up, one we can’t handle reflexively or habitually, when we’re deliberating while making motor decisions.

Which is to say that consciousness is not just one thing, but a multi-layered melange of functionality. You know. A hierarchy. 🙂 (Although there’s an issue with my hierarchy I might post about sometime soon.)

LikeLike

I’ll need to look at this more closely but my gut feeling has always been that there are not different types of consciousness but just different types of things we are conscious of.

LikeLiked by 1 person

The “types of consciousness” language can be confounding at times. Sometimes it means different processing in different regions of the brain, other times it refers to the same thing from different perspectives. The dispute here is between people who mean the A-consciousness / P-consciousness distinction in the first sense, and those who mean it in the second.

And there are people who use that language in the sense you mentioned, being conscious of different things. This can be further confounded by the fact that being conscious of different types of things involves processing in different parts of the brain, although in your sense, we’d expect a lot of overlap.

LikeLiked by 1 person

When you or others talk about minimal consciousness in, for example, arthropods, what is meant? Are there gradations of consciousness?

Or, is the difference between an insect consciousness and human consciousness not consciousness per se but rather the unconscious neurological capabilities which control the types of things of which an organism might become conscious?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Well, I suspect it depends on who you ask. For me, it’s gradations. I think a creature with minimal consciousness is less conscious than one with episodic imagination, or introspection. I don’t think there’s any magical moment when the lights suddenly come on, no bright line where non-consciousness is on one side and consciousness the other.

Some people will say that once you have mental imagery and affects, you have consciousness, period. But there can be wide variances in the acuity of that imagery, and in the ability to form associations on it, as well as the sophistication of affects, from the four Fs (feeding, fighting, fleeing, mating) to complex social emotions.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Still is the acuity or even the episodic imagination really a function of the unconscious neurological capabilities? I’m inclined to think they are. I would say almost for sure that things have like episodic imagination certainly require a major unconscious neurological underpinning.

LikeLike

It seems like everything that makes it into consciousness is the result of a lot of unconscious processing. I guess the question is, is there a difference in the conscious content between a creature with minimal consciousness vs one with imagination or introspection?

If I ask you to imagine a cat walking in the yard, the image that pops in your mind, adjusted for differences in sensory capabilities, probably isn’t that different from the one a minimally conscious creature has on actually seeing a cat walk in the yard (albeit less vivid), raising the question of whether the imagination functionality is just unconscious framing.

Although if I ask you to imagine a pink bear climbing a giant 80 foot tall brownie, the image that forms in your mind is not one I would expect a minimally conscious creature to ever have.

And then there is the issue of aphantasics, who don’t have the ability to hold imagined images in their mind. Yet, they can still consciously understand the concept of a pink bear climbing a giant brownie. So they have imagination minus the imagery, which to me, implies that there’s still an addition of some type to consciousness.

That, and our “raw” conscious experience has all our various abilities blended in. A lot of the richness of our experience comes from that blend. A creature with far less in their blend is going to have a less rich experience.

LikeLike

“Although if I ask you to imagine a pink bear climbing a giant 80 foot tall brownie, the image that forms in your mind is not one I would expect a minimally conscious creature to ever have.”

I would agree but is the ability to imagine a product of conscious or unconscious activity. Even if a mixture, I would imagine a good bit of unconscious.

Is there a fundamental difference in the consciousness of blind person from birth with someone not blind from birth? The blind person can’t have visual images but is that person’s consciousness lesser than the non-blind person.

LikeLike

My understanding is that blind people still have a visual-like world map. It’s just constructed from other senses. If born that way, a lot of the visual circuitry gets recruited for other purposes, probably adding extra processing capacity for the other senses.

But they never experience the redness of red.

So maybe the way to think about it is their consciousness ends up being lesser in some aspects and greater in others.

Unless their blindness is due to brain damage or pathology, then they may well have aspects of their consciousness missing.

LikeLike

For myself, I want to say what Consciousness is “made of”. I want to say what the minimal conscious-type process is. From there you can ask what various things do with conscious-type processes. Some can be simple, as in simpler arthropods. Some can be complex, as in really complex arthropods like us. So I equate the idea that something has more consciousness with the idea that something is more alive. Are you more alive than a snail? I guess I might be alright with equating the amount of consciousness with the complexity of conscious-type capabilities.

*

LikeLike

I totally understand the desire to understand what consciousness is made of, or composed of. It’s what drives a lot of my reading and posting on it. It’s just that I haven’t found that there’s one definite thing that “consciousness” refers to, but a hazy and shifting collection of processes and capabilities.

Life is a good analogy, because it has its own definitional issues. Are viruses alive? What about viriods? Or prions? It depends on what we consider the minimal attributes necessary for life. Can we get by with just reproduction? Or must it evolve? What about homeostasis? If viruses are alive, are they less alive than we are? What should we make of the fact that they can reproduce and evolve faster than us?

LikeLike

I don’t consider proposing various “this and that” types of consciousness to be a helpful way for theorists to take this either. It seems to me that they should provide specific definitions for the “consciousness” term that they use, and then go about describing their conception of that idea’s functional dynamics. Adding different forms of consciousness, such as “access”, “interoceptive”, “extroceptive”, and so on, should tend to delude the original definition. Furthermore given the many separate ways that people define “consciousness”, Mike has even had to present a diverse hierarchy for this term that makes room on a scale from panpsychists to the most restrictive higher order theory. Effective science tends to need effective reductions however, so the sooner that his tool is able to be retired, the better!

Here’s a quick run through my own psychology based consciousness account:

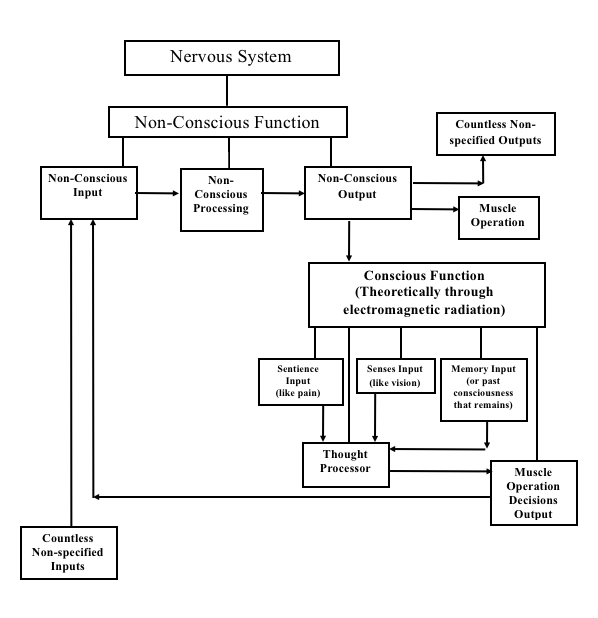

Theoretically we have an entirely non-conscious brain and it produces a separate sentient entity somehow (perhaps through the electromagnetic radiation associated with neuron firing). Thus there is phenomenal consciousness (or just plain “consciousness”), though as such it shouldn’t yet be functional. Apparently evolution tends to add various further elements to the sentient entity which yields a teleological dynamic though. (The following function enhancing elements are where others tend to muddy things up by defining additional varieties of consciousnesses.)

The functional sentient entity tends to also be provided with an informational input that we commonly refer to as “senses”. Note however that a given smell for example will harbor both phenomenal components which feel bad and good, as well as perfectly informative dynamics. Even vision seems mixed given that visual information can provide “beauty” and so on.

The sentient entity also tends to be provided with a dynamic by which past conscious experience is preserved for future use, or “memory”.

From this model an output of the brain produces a second variety of function through a sentience input (or “consciousness” itself), a current information input (or “senses”), and a way to access past consciousness once again (or “memory”). Given its desire to feel good it will interpret these inputs and construct scenarios about what to do (or “think”), and the non-conscious brain will detect actionable decisions and so operate the desired muscles. Here’s my most recent diagram for this model.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Eric,

As I noted to James, I think the idea of “types of consciousness” can mean a variety of things in its own right. It can mean different definitions in a hierarchy (as I present it) but always a unified system of increasing capabilities. Or it can mean being conscious of different things, which is mostly what F&M mean by their exteroceptive, interoceptive, and affective distinctions.

The A-consciousness / P-consciousness debate is actually in terms of what the distinctions between these types actually mean. For a cognitivist, there is just consciousness, with access being the objective account, and phenomenal being the subjective one. But to Block and company, it implies actually different processing in different parts of the brain. This last, I agree, is unproductive.

On definitions of “consciousness”, I fear getting one definition is a forlorn exercise. At best, it might come down to some standards body declaring a definition, such as the IAU defining “planet”, that everyone will then hate and ridicule. One that won’t even eliminate modifiers such as “primary consciousness” or “self consciousness”, just as the IAU couldn’t stamp out “dwarf planet”. Although it might at least standardize language in scientific papers.

(If some body does tackle it, hope they also address words like “feeling”, “affect”, and “emotion”, along with finding some standardized terminology for non-conscious impulses and reactions.)

On your model, my usual question: how does the sentient entity, the conscious function, work? It seems like if your theory of consciousness includes a conscious component, if it doesn’t reduce the conscious to the nonconscious, you’re not done yet. (Although maybe you are for your ethical framework purposes, just not my goal of understanding consciousness itself.)

LikeLiked by 1 person

Mike,

Surely there are few things more trivial to a scientist than how some commission defines the “planet” term. Science will explore massive objects based upon their specific measurements, not based upon what they’re officially called. The “planet” term seems to exist for non scientists to fantasize about as some kind of Wittgensteinian ideal. No harm, no foul.

That’s not the case for every term in science however. Consider how Newton established the usefulness of force as accelerated mass. I’m not suggesting that some commission will proclaim consciousness as such and such. I’m claiming that in order for our mental and behavioral sciences to finally begin hardening up, they’ll need to develop various effective definitions for crucial terms in their domain. It seems to me that the medium through which we experience existence, sometimes known as “consciousness”, will surely be one of these terms. A revolution in science seems needed here, and note that even the original Newton didn’t need to provide his emerging field with effective principles of metaphysics, epistemology, or axiology.

Regarding my conception of how conscious function emerges from non-conscious function, you know I’m not much for neuro speak. I’ll give you the following synopsis anyway though:

Your peripheral nervous system feeds your brain information about your body in general. Sometimes information is received from it which sets up neuron firing that’s able to go “global”. But I don’t consider the associated information in itself to create conscious experiences because that seems to violate my own metaphysics of causality (as displayed by my “thumb pain” thought experiment). A conscious experience will thus require associated mechanisms in a natural world. This global firing does create electromagnetic fields which exist as such mechanisms however. They create something (theoretically “you”, actually) that experiences an itch square in the middle your left foot. (This is represented on my diagram under two input headings. The irritating part of the itch is under “sentience”, while the informative part that tells you where the problem resides is under “senses”.) The irritation motivates you (and still an entity which exists as em fields) to construct scenarios about how to end this irritation, or “thought” in the diagram. A decision is made to take off your shoe for a good scratch, and your non-conscious brain detects these decision patterns in your em fields and thus operates the associated muscles as instructed by you, still a product of these fields.

So that’s my dual computers model of consciousness — the first consists of the brain, while the second consists of em fields produced by the brain.

LikeLike

Eric,

“It seems to me that the medium through which we experience existence, sometimes known as “consciousness”, will surely be one of these terms.”

The more neuroscience I read, the less I agree with this. “Consciousness” seems to refer to an amorphous and hazy collection of capabilities. From a scientific perspective, the thing to do is investigate each of those capabilities, and the manners in which they interact. In other words, the consciousness concept may play a role similar to what you envisaged above for “planet”.

“They create something (theoretically “you”, actually) that experiences an itch square in the middle your left foot.”

This seems to be the point where you cross from a non-conscious system to a conscious one. But “create something” isn’t really explaining what’s happening here. What’s involved in the creation? What is “something”?

You don’t have to answer these questions. But they are the ones I’m going to ask of any theory of consciousness at the moment where it crosses that line.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Here’s my take folks. Conflating the term consciousness with the phenomena of mind is fundamentally flawed and is actually the cause of all of this mass confusion underwriting the debate. Here’s just one example: Mike said, “Some people will say that once you have mental imagery and affects, you have consciousness, period.” If Mike is willing to jettison the term consciousness for the word mind, then his ontology will match that of Philosopher Eric’s if, and only if Eric himself is willing to replace the term consciousness with the word mind also. Eric’s ontology then become a coherent architecture, one that posits the physical phenomena of mind emerging from the physical phenomena of a brain, thereby placing both mind and matter in the same category with no ontological distinction. From a naturalist perspective, I do not see this explication as problematic.

A literal definition of consciousness will require two fundamental aspects in order to be tenable. First, it has to be more closely aligned with Chalmers rendition: an experience of likeness or “what it feels like to be some-thing” and second, consciousness must be a physical form of some kind. Descartes mind already knows what it feels like to be a mind, and so does every other mind. What the mind doesn’t know is what every other physical system in universe feels like. But that epistemic gap takes nothing away from the fact that it feels like something to be a mind, and that physical “some-thing” (mind) emerges from a physical brain.

Peace

LikeLiked by 2 people

I’ve been trying to come up with ways to explain the epistemic gap. Let me know if this works:

There are two kinds of knowledge which I call abstract and hard-wired. Consider this scenario: You have a camera watching a room, and a computer which recognizes cats watching the camera video. When a cat is in the room, the computer turns on a light in a separate room. You’re sitting in that separate room.

So a cat walks into the room and the light goes on (and the cat food door opens). That light being on is a hard-wired, subjective kind of knowledge you cannot share with anyone not in the room with you. Abstract knowledge is about abstract patterns. Different systems can have the same or similar abstract knowledge. But hard-wired knowledge is necessarily subjective, available only to the system in question.

Does that help anything?

*

LikeLike

So the light is subjective experience, a quale, or a collection of qualia? But if so, what about it makes it private and unshareable? The fact that we don’t have a similar line from your room to mine?

Or I completely missing the point? (Very possible.)

LikeLike

The light is a symbolic sign which carries mutual information relative to a “cat” pattern. That “cat” pattern is what we usually think of as the quale, I think. A different light, for example a “dog” light, would be essentially physically the same, yet it carries mutual information relative to a different pattern. If you have not assigned labels, there is no way to differentiate them besides saying “this” one and “that” one.

What makes it private is that it can be hardwired to other stuff, like labels, and memories, and actions. You can’t share that hardwiring, the “response” part of the experience. (And there is no experience without a “response” part.) A third person might be able to see and understand the hardwiring, but they couldn’t “have” it.

*

LikeLike

Ah, okay, I see what you’re driving at. My way of putting this is that only the original system A can have the experience, that is, have it merged into its unique state driven by its unique history. System B might understand A well enough to examine its state and processing to deduce what that experience is, but B can’t have the experience since the same sensory data would have different (albeit possibly very similar) effects on its state.

Sound right?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Lee,

If we talk about consciousness existing aside from a mind in the panpsychist sense, then it seems like we’re talking about some property without mental imagery, volition, imagination, introspection, memory, or affective feeling. I have a hard time seeing how something without those things can have “what it feels like to be some-thing”. Those capabilities seem like the underpinning of that state, how it’s brought about.

Maybe I should ask, what leads you to conclude that they’re separate?

LikeLike

“I have a hard time seeing how something without those things can have “what it feels like to be some-thing”.

Your statement is a subjective response Mike, not an objective one. You are failing to see that the properties of any physical system described by physics “is” the experience of that system. The only systems that are beyond the reach of physical descriptions are the quantum world and mind. Just consider a simple example: a blood cell is some-“thing”, am I right? It’s a physical system just like mind is a physical system. The only thing that makes those two systems different are the properties that underwrite those systems, and those unique properties “are” the experience of the system.

Just because you don’t know what the properties of a blood cell might be and/or how those properties might feel does not limit your ability to be objective. If you and others choose to have tunnel vision, insisting that the terms mind and consciousness are the same thing, then everyone will continue talking past each other.

“…what leads you to conclude that they’re separate?”

Not sure I understand this question????

Peace

LikeLike

Lee,

I don’t see mind and consciousness as equivalent, but I do think consciousness requires a mind. I can reduce the concept of experience enough to find it in a blood cell, but it seems to end up being a version I don’t find interesting. It doesn’t seem to get us closer to understanding our experience and the ones in systems similar to us.

My question was why you’ve concluded that consciousness is separate from mind? What makes that conclusion compelling for you?

LikeLike

I have not concluded that consciousness is separate from mind. I am positing a definition of consciousness that includes all systems, including the system of mind.

Let’s put this into perspective Mike: At a fundamental level, you have no idea what it feels like to be me because that properties that underwrite my unique experience are not the same properties as yours and still; as a physical system yourself, you may not find me interesting either.

Fundamentally, our experience is the same experience as all physical systems, an experience that you just might find interesting. But if you want to limit your inquiry to systems that are similar to ours, you are free to do so.

Peace

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m trying to make a point here Mike: What makes us all similar and yet, exclusively unique as systems of mind are the properties that make up those minds, (the brain); and those properties that make us both similar and unique are the experience, or what “It feels like”. So it is with every physical system in the universe unless one posits an ontology of dualism. From a naturalist perspective, I don’t find this rendition of pragmatic panpsychism problematic….

Does that make any sense to you???

Peace

LikeLike

Lee,

I understand the argument. A lot hinges on exactly what you mean by “experience” and “it feels like”. The word “feel” implies, at least to me, some sort of valenced feeling. It also implies perception, models of the environment, and memory. Those things definitely apply to many animals. We can identify specific physical components that provide those capabilities. Even with the most liberal interpretation of those terms, I can’t see how we can identify that functionality in rocks, protons, or a dead brain.

What would you say I’m missing?

LikeLike

What I would say you are missing is that a rock is a system, and just like any other physical system a rock has properties. Those properties are unique to any given rock and the properties are the experience of the rock. We may not know what it feels like to be a rock, but just like us, the rock does not experience it’s properties in a vacuum, that experience is a give and take relationship with the chemical make up of the rock, the natural world, gravity, pressure, wind, rain, tectonic plates shifting, etc.

I just think it’s absurd to project our own unique experience of mind, with all of the unique properties that make mind onto the natural world and then call that experience consciousness. That anthropocentric rationale irrevocably reduces to dualism. Dualism is a child of the SOM paradigm and dualism is a rabbit hole that even the most fervent panpsychist’s are unable to avoid, including the likes of Chalmers, Coleman and Goff.

Peace

LikeLike

Lee,

This is where I bring up the little hierarchy I use to keep these kinds of concepts straight. I’ve added an extra level 0. (I don’t mean anything by the zero itself, just that I have to use something to put it before the level I usually label “1”.)

0. A system is part of the environment and is affected by it and affects it.

1. Reflexes and fixed action patterns.

2. Perception: models of the environment based on distances senses, expanding the scope of what the reflexes react to.

3. Volition: action selection, choosing which reflexes to allow or inhibit, based on valenced assessment of cause and effect prediction.

4. Imagination: expansion of 3 into action-sensory scenario simulations.

5. Introspection: predictions of the system about itself, enabling symbolic thought.

The higher up in the hierarchy we go, the smaller the number of systems that exhibit it. 0 represents all matter, 1 all living things. 2-4 apply to increasingly smaller number of animals species, and 5 to humans.

I see the rock as at the bottom level. We can call its state changes “experience”, but we have to remember what that experience would be lacking.

I do agree with one aspect of pragmatic panpsychism, that there’s no bright line between conscious and non-conscious systems. But my way of thinking of this is as gradual emergence rather than everything being conscious. In the end, it might amount to how one wants to look at the world and what kind of terminology they want to use.

LikeLike

I hate to keep referencing this, but here’s the conundrum Mike. Even the notion of pragmatic panpsychism is hamstrung by the prism of subject/object metaphysics. SOM is a the prism through which we view the world and that model has divided the world into two parts, mind and matter. Once that division occurs, there is no way to put the world back together again without eschewing SOM and replacing it with something else. That’s the bottom line on the debate surrounding consciousness.

If one is willing to entertain reality/appearance metaphysics or RAM, all of the intractable problems created by SOM are eliminated. Then a definition for consciousness can be developed, one that is all inclusive, accommodating both mind an matter under a single manifold of monism; a manifold where valance then becomes the driving force behind motion and form. According to RAM, value comes first in any hierarchy, a hierarchy that makes value sovereign, a hierarchy where value is longer a relation between a “subject” and an “object”.

I am old enough to know that I cannot convince anyone of any-thing, so keep on blogging Mike…..

Peace

LikeLike

Thanks Lee. I’m old enough too to know that persuasion is an uncertain and long term exercise. All we can do is keep presenting our ideas to each other until maybe one or both of us get it one day. So please, keep on presenting your view…

LikeLike

Lee,

Do you really think a rock has experience?

I think bottom line I am fine with a weak dualism. There are things in the world with experience and things without it. Experience itself may be (probably is) a part of some underlying monistic reality but it is useful to distinguish it from the rest of reality because it is a system with agency of its own.

LikeLike

James,

The prevailing models of panpsychism are intellectually and physically untenable because there is no clear definition of consciousness, a definition that will accommodate the notion of “experience”. From our own anthropocentric perspective, “experience” is associated with all of the attributes and features that make mind, along with all of the coy terms like qualia. As long as the notion of mind, its features and/or attributes are used as a reference point for defining the term consciousness, panpsychist’s will be easy prey for anyone who wants to challenge their position, so will materialist, idealists and those who call themselves naturalists.

My model resolves the “hard problem of consciousness” by asserting that the properties of any physical system are the experience of that physical system; (properties = experience). The inverse asserts that the experience of any physical system is defined by the properties of that physical system, (experience = properties).

So, to answer your question; do I really think that a rock has experience? Does the rock have well defined properties? I don’t have to like the answer, but if I do the math it works. The greater question that should be considered is this: How does one overcome the subjective gap?

Peace

LikeLike

“So a cat walks into a room…” (let’s call it a bar). And the bartender says, “Hey, you’re a walking cat”. The cat replies, “What, you think you humans are the only one’s who can walk on two feet? But, hell, after another whiskey I’ll probably be walking on all fours.” No disrespect JamesOfSeattle.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Jeff, I think I’m detecting a cat pattern here.

Wait. Are you yourself a cat secretly releasing cat propaganda? Or have you just been taken over by them?

LikeLike

Oh, please. I’ve been taken over by cats for years. I’m simply over-run. Damn things won’t stop yammering on and on about consciousness, always insisting that their’s is superior to our’s. , My newest cat, however, a price-less little albino, is much less troublesome—she drinks only beer.

LikeLike

Well, it’s well known that the cats rule the world. They simply tolerate our business, as long as we supply nourishment.

There are few worse things than a beer drinking cat.

LikeLike

How about an alcoholic ferret?

LikeLike

Sounds a little weaselly to me.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Sounds a bit weaselly—but always good stuff. This pandemic has for some reason driven me deep into the weeds of flippancy. Pandemics come and go—cat jokes, however, are forever.

LikeLiked by 1 person