The other day, when discussing Mark Solms’ book, I noted that he is working to create an artificial consciousness, but that he emphasizes that he isn’t aiming for intelligence, just the conscious part, as though consciousness and intelligence are unrelated. This seems to fit with his affect centered theory of consciousness, and it matches a lot of people’s intuition.

But I’ve often wondered why this intuition is so prevalent. I suspect it comes from the impressions we have have about our own experience. Subjective phenomenal experience seems like something that just happens to us. We don’t appear to have to work for it. On the other hand, doing things that are typically considered intelligent, such as working with mathematical equations, handling complex navigation, or dealing with complex social situations, typically require effort, notably conscious effort, at least until we learn them well enough for it to “be natural”.

From this, it seems easy to reach the conclusion that these are very different things. It doesn’t help that the definitions for both concepts are controversial. I’ve talked about the definitional issues for consciousness many times. Intelligence faces similar issues, although its definitions don’t seem to vary across nearly as wide a range as the consciousness ones. It’s worth noting that some of the definitions in its Wikipedia article overlap with particular definitions of consciousness. But intelligence is usually regarded as something that can exist to highly varying degrees, including far below human level intelligence.

The problem is that the impression of separate phenomena is based on introspection. And as I’ve discussed before, introspection, while adaptive and effective enough for many day-to-day purposes, isn’t a reliable source of information about the architecture of the mind. There is extensive psychological evidence showing that our knowledge of our own mind is limited.

We don’t have access to a vast amount of unconsciousness and preconscious processing that happens in the brain. For example, the firing patterns in the early visual cortex are topographically mapped from the retina. The retina has a small central area of high visual acuity (resolution), the fovea, but that acuity falls off dramatically toward the periphery of the retina, as does the number of color receptors. And we have a hole in the center of the fovea where the optic nerve is. That and the eyes are constantly moving reflexively.

But we don’t perceive the world through a constantly shifting acuity tunnel with color only at the center. Our visual system does an extensive amount of work to produce the experience of a stable colorful field of vision. And that’s before we get into detecting things in motion as well as object categorization and discrimination. When we recognize something like a red apple, it seems like something that happens effortlessly to us. In reality, our nervous system has extensive layers of functionality, functionality hidden from introspective awareness. A lot of processing has to take place for us to recognize that apple.

This is also true for the initial quick evaluations the nervous system makes about the results of all that perceptual processing, the initial evaluations we usually call “affects” or “emotional feelings.” Again, all leading to an impression that sentience simply happens to us, rather than something our brain puts in a lot of work to produce.

Artificial neural networks that recognize images or make evaluations are considered artificial intelligence, which implies that the natural versions are also a form of intelligence. In other words, conscious experience is built on intelligence. Most of it is unconsciousness intelligence, but intelligence just the same.

That doesn’t mean that consciousness and intelligence are equivalent. There are plenty of systems that meet many definitions of intelligence but show no signs of meeting typical definitions of consciousness. Often intelligent technological systems involve encyclopedic information, not the world or self models more likely to trigger our intuition of a conscious being. And plants and simple organisms like slime mold often exhibit intelligent behavior that few regard as conscious.

But it does imply that consciousness is a type of intelligence, that’s built on lower levels of intelligence and enables more complex forms of it. As most commonly understood, it seems to be a form of intelligence involving the use of predictive models of the environment, the self, and the relationship between the two.

This is a conclusion many seem loathe to accept. Insisting that consciousness is something separate and apart from functional intelligence inevitably makes it more mysterious, more difficult to explain. It’s notable that in his 1995 paper in which he coined “the hard problem of consciousness”, David Chalmers explicitly noted the functional areas of intelligent processing, labeling them “the easy problems”, but then declared that wasn’t what he was talking about, in essence excluding them as possible answers to the problem he was identifying.

The result is a phenomenon many seem to think science can’t solve. It’s some of the factors that I think lead to outlooks like panpsychism, biopsychism, or property dualism, as well as appeals to theories involving quantum physics, electrical fields, or other highly speculative notions. But if consciousness is just a type of intelligence, then studying its mechanisms is possible, and everything we need should be in the mainstream cognitive sciences, including cognitive neuroscience.

What do you think? Are there reasons I’m overlooking to regard consciousness and intelligence as separate phenomena? If so, what distinguishes them from each other? What properties does consciousness possess that intelligence lacks, or vice-versa?

Yes, I see consciousness and intelligence as related. But the relation isn’t all that obvious.

Intelligence has been misunderstood, since forever. It is still misunderstood.

Somebody solves a problem using logic. And people decide to equate intelligence with logic. That’s a huge mistake. Logic itself is just mechanical rule following, as we see with our logic machines. There really isn’t anything intelligent about that. It is just mechanics.

Somebody sees a problem. So he comes up with a logical model for the problem, and then solves that with logic. But the intelligence is not in the logic. The intelligence is in the ability to construct useful models.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Interesting point about intelligence. Although I wonder if it’s actually a distinction between a narrow and more general intelligence.

If intelligence is the ability to construct useful models, what is happening during that construction? What’s needed beyond value and logic? Creativity? But what is creativity other than the use of unexpected logical models? (“Unexpected” meaning it’s not in the observer’s current model of solutions.)

Consider when I use Google Maps on my phone. I’m essentially giving it my destination and letting it figure out the optimal path to that destination, taking into account known construction, traffic issues, etc. Often, when I use it for a destination I already know how to get to, I’m surprised by the shortcuts it comes up with. (Although sometimes I’m also underwhelmed by its blind spots.)

The question is, when I figure out a path to a destination, am I doing something substantially different than Google Maps? Certainly I make take into account additional factors (and my own blind spots), but beyond that, what am I bringing that the navigation system lacks?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Perception, experience, pragmatics.

Our models are derived from our understanding of the world around us. Computer based attempts at perception are quite poor, and computers don’t really do pragmatics though they may attempt to emulate it.

Your Google Maps example is interesting. My wife recently printed out the map to a destination a few miles away. The suggested route required turning at a difficult to find intersection. So I just went by my more normal driving instincts instead. In retrospect, the google route would have been shorter, but probably slower.

Yes, I think you are doing something different from google. Presumably, google is using metrics. Perhaps you are too, but your metrics are likely biased toward what is familiar to you.

LikeLiked by 1 person

The question is what’s involved in perception, experience, and pragmatics aside from value and logic.

The story you describe resembles my experience in the early days of navigation systems. I remember my Garmin doing things like that to me. But in recent years, I’ve found those kinds of occurrences increasingly rare, although they definitely still happen. Of course, I sometimes make a mess of things when I just do it myself

LikeLiked by 1 person

What’s mostly involved in perception, is information. And I’ll get back to that shortly.

Yes, pragmatics depends on value. Our biology gives us a natural value system, which we call “emotion” and we often decry it. That’s a mistake. My current assumption is that emotions are biological, and are the way that our biology tells us about the state of our life support systems — but, of course, that’s surely an oversimplification. In any case, emotions provide us with feedback from our biology.

Back to information. We make a huge mistake by assuming that information is a natural kind. It is all human constructed. And sure, other biological organisms are constructing information too. If you want to understand consciousness, then start by trying to understand perception. And if you want to understand perception, then look to how we construct information.

To construct information, we categorize the world (divide it into categories). Information amounts to information about categories. And the more finely we categorize the world, the more detailed the information that we can have.

Newton’s laws worked so well because of the way that he reconceptualized motion. With the Newtonian conception, we could now have friction as a force, air resistance as a force. These are new categories which weren’t available to Aristotle. And those new categories gave us access to new information and better predictions.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I agree that information is a crucial part of all this. But I think it is a natural kind. Talk to any physicist and you’ll hear a story about physical information, which is everywhere. (The black hole information paradox is meaningless without it.) The key thing is, any physical information has the potential to become conscious or useful information, which is what I think you’re using “information” to refer to. But the physical information exists before we make it useful info and can continue to exist after we cease using it.

Emotions are biological, but they’re also something our brain constructs based on what it senses in that biology, an automatic evaluation based on what is being sensed about the system’s homeostatic state, which we only know as conscious feelings. It’s all information processing, although it doesn’t seem like that from the inside.

LikeLiked by 1 person

What physicists mean by “information” is not the same as what most people mean. Physicists are typically talking about the transmission of signals. Most people are concerned with semantics rather than with raw signals.

LikeLiked by 1 person

While reading your explanation and the examples you presented, I was struck by the ambiguity of the word intelligence.

Much of what appears to be ascribed to intelligence might be more akin to the label “awareness”. AI, currently is not intelligent. Perhaps we should be calling it AA, artificial awareness. Linking awareness to behavioral response might look like intelligence, but it’s not, right? Slime mold might react given some biological awareness it possesses, but it’s not “smart”. I would think that to apply the word intelligent, that some intentional decision making would be involved. Choices to be made.

Maybe there’s a hierarchy here:

• Awareness

• Sentience

• Intelligence

• Consciousness

and an overlapping spectrum within each level, each one blending into the next?

LikeLiked by 1 person

There is definitely a lot of ambiguity attached to “intelligence”. When we use the word, it’s often context specific. Is a bee intelligent? The question only makes sense in comparison to something else. Compared to a dog? No. But compared to an ant it’s a super mind. On the other hand, “intelligence” seems less ambiguous than “consciousness”; I don’t see anyone claiming a rock or proton has intelligence.

I like the way you’re thinking with the hierarchy! Unfortunately the other terms are all pretty ambiguous themselves. It makes having productive conversations challenging. We always have to be on guard that we’re not talking past each other with different definitions. (I’m convinced most philosophical disputes are definition disputes.)

For example, does it make sense to say a self driving car that brakes because of a pedestrian in the road is “aware” of that pedestrian? Or to say in that Tesla crash that killed a driver that the car was “not aware” of the truck it slammed into?

Sentience we could at say is awareness of an initial primal evaluation. But many people would say that’s also consciousness. And quite a few would insist it’s more primal than awareness. 😛

LikeLike

Perhaps you saw this recent article? https://aeon.co/essays/does-consciousness-come-from-the-brains-electromagnetic-field

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, I have. And a number of people have pointed it out to me. There are some fans of EM theories here, but I’m not enthusiastic. Strictly speaking they’re not impossible, but they’re just disconnected from where most of the data in neuroscience is pointing.

Anil Seth did a brief Twitter thread on them a while back.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hey Anonymole, it sounds like you may be interested in McFadden’s proposal! I certainly am. Note that his is falsifiable while the standard sort of theory favored by prominent people like Anil Seth (which you might notice to always depend upon certain information that’s processed into other information), is not falsifiable. So while these people must stomach all sorts of funky thought experiments from the likes of Searle, Block, Schwitzgebel, and I, the fate of McFadden’s theory will instead depend upon scientific experimentation.

What sort of experiment would support or refute his theory? I emailed McFadden a proposal on Saturday, and now that it’s Monday I’m hoping that he’ll get back to me. But who knows since he’s a prominent person while I’m just a fan. Anyway here’s what I sent:

LikeLiked by 1 person

Two thoughts, 1) running interference on a signal source should be doable from outside the brain. If true, then one might believe we could “turn off” consciousness this way.

2) As I lay in bed, my internal monologue running rampant, I thought, is there an EM field being generated that’s allowing me to have these thoughts?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Actually Anonymole, one of the major charges against McFadden’s cemi is that if true then consciousness should be altered by all sorts of exogenous EM fields, though this isn’t observed. When the associated physics happens to be calculated out however, this rebuttal may be dismissed. He addresses his in his 2002 paper entitled “Synchronous Firing and It’s Influence on the Brain’s Electromagnetic Field”:

My take is that the brain seems to be relatively insulated from standard EM radiation, whereas the static nature of the MRI variety leaves that potential relatively benign, and then the non static nature associated with Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation will of course have physiological effects, since here electric current becomes inducted in specific parts of the brain. I guess it’s used therapeutically to stimulate neuron firing, though must be used carefully given its neural effects. My embedded transmitter proposal seems to get around all this by doing the same sorts of things that groups of neurons do right in the head, though unlike neurons which are wired up parts of the brain, this transmitter would only produce EM radiation to see if this could alter a theorized EM wave that exists as consciousness. If this isn’t a good way to test his theory, then I’d love to know why.

Regarding your curiosity that perhaps there’s an EM field which allows you to think, technically the theory is that there’s an amazingly complex EM field which actually constitutes all of your thoughts, memories, perceptions, and qualia in general. So theoretically as this wave changes, your consciousness changes in associated ways.

I’m certainly here for more if you (or others) have questions or comments, though the following is a spot on McFadden’s homepage where he gives a general overview, offers his two 2002 papers on the subject, a book chapter he wrote for a 2006 consciousness book, two 2013 papers, and most recently his 2020 paper, all accessible from PhilPapers. https://johnjoemcfadden.co.uk/popular-science/consciousness/

LikeLiked by 1 person

My two cents.

I wonder if anybody tried to look at similarities and differences between consciousness and intelligence ONLY from a definition perspective, without diving into his understanding of what those things are? That could be a different option for how to view the problem.

How the most accepted definitions evolve? Are they going to be more strict or broader? Do they overlap more or less? Do we have more clarity or more ambiguity with more recent definitions? The list of questions goes on and on. How this approach relates to our typical discussions on the topic? Is it helpful, neutral, or misleading?

I don’t have data, but I feel that nobody tried to apply such an approach to any subject.

On a cheerful note – AI could probably, use this approach much better than us.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I don’t know if there have been many studies along those lines. I actually googled around yesterday to see if anyone had addressed it. I came across a page or two which had fairly mystical takes on consciousness. There were a few philosophical papers, but not as much as you might expect, and nothing from neuroscience that immediately jumped out. It seems like something that should be explicitly studied.

I suspect most people who see access consciousness as consciousness would have a take similar to mine. On the other hand, people who see phenomenal consciousness as something separate and apart from access consciousness I tend to think would see them as very different.

LikeLike

It depends rather strictly on how one defines those terms.

With regard to Chalmers, the functions of the mind — it’s intelligence, so to speak — is a task that does seem within sight (“easy”). That aspect of mental function seems clearly to fall within the rules of physics. But why there is “something it is like” to be conscious has no physical explanation that we know of. Which why some resort to some form of panpsychism; it provides an explanation where there is none. Others (yourself, I believe) feel a complex enough function just has an aspect of there being something it is like to be that mechanism. You may turn out to be right, but there are currently no physics that explains it.

(BTW: second paragraph, first two sentences. “…why people this intuition…” and “… impressions we have have about…” Looks like a “have” did a runner!)

LikeLiked by 1 person

I definitely agree it depends on the definitions. Unfortunately, this is an area where ambiguities are pervasive.

Along those lines, the question I would have is, what does that very common phrase, “something it is like”, mean? (Other than its synonyms: subjective experience or phenomenal consciousness.) Until that can be clarified, it feels like saying there’s no physics to explain it is equivalent to saying there’s no physics to explain the color of 5.

If we mean having a point of view, a perspective from a certain physical location, a certain way of processing information, or due to a particular history, then it doesn’t seem like anything a robot couldn’t have and so nothing particularly mysterious.

(Thanks for the catch! Last minute edits always bite me. Updated!)

LikeLike

Yep, and those ambiguities make the discussion rather fruitless. FWIW, my own definition of “intelligence” — the ability to intentionally figure out a problem — makes it quite different from consciousness — for which I do think Nagel’s famous phrase makes a good litmus test.

With regard to that, comparing it to “the color of 5” says more about your disdain than anything else. I see it as quite simple and clear-cut. For humans it’s the sum total of everything it means to be human — something that is well recorded in our stories and our art. For a dog, it’s something different and, to us, so far quite as elusive as it is for Nagel’s bat.

To return to the overall point, the “hard problem”, it’s something that no physics we know would account for in any robot we’re capable of constructing. As far as we know, there is nothing “it is like” to be any kind of machine.

LikeLike

It’s true that I don’t have much regard for the phrase. But I’m open to the possibility that’s a hasty judgment. I could see it as a possible tag for something more complex, similar to terms like “natural selection” or “supply and demand”. But if I ask what those mean, answers that allow a deeper dive are readily available, with each successive explanation being in ever more basic terms.

What is it about the sum total of what it means to be human that implies no possible physical explanation? Certainly there remain plenty of gaps in knowledge, but I can’t see anything that can’t at least plausibly be explained in terms of psychology, neurology, biology, chemistry, or physics.

I know we won’t settle this here, but this failure to be able to drill down to exactly what is unexplainable is why I don’t see the hard problem as a real problem (other than as the sum total of the “easy” problems).

LikeLike

What physics accounts for phenomenal experience? Can you drill down on what physics, what mathematical equation, accounts for it?

What you’re missing here is that terms such as “natural selection” and “supply and demand” represent well-understood and well-defined concepts. There is no debate over their meanings. But consciousness is currently so opaque we don’t have an agreed upon definition, let alone an understanding of it. That alone speaks to it being a “hard” problem.

Nagel’s phrase, as I said, makes a pretty good litmus test in my eyes. Is there something it is like to be a rock? How about an insect? How about our laptops? Is there something it is like to be a laptop?

What about a fish? My fishing buddy and I have often discussed whether fish have mind. Does the apparent distress and terror of a landed fish mean what it seems to mean, or is that just reflexes trying to return to the water? A telling point, I think, is that one could program a robot fish to act indistinguishably.

But what about a dog? Can anyone who has looked into the eyes of their dog doubt there is something it is like to be that dog? Can a robot dog come anywhere close to the real thing?

When we finally achieve some real understanding of consciousness, then we’ll be able to drill down on the something it is like to be a conscious entity, but until then it remains a challenging mystery.

LikeLike

The problem with asking what physics accounts for phenomenal experience is that’s just another way of asking what physics applies to “something it is like”. We’re just going in circles. Getting more specific might give us a chance of addressing it.

For example, do we mean being able to discriminate between a red flower and a green leaf? Or telling between hot and cold surfaces? Or what emotions the red flower triggers? There are cognitive neuroscience insights on these more specific questions. It’s far from complete, but there’s nothing in principle indicating the answers aren’t available.

The problem I see with Nagel’s phrase is it seems like just a front for our intuitions and biases, just another way to say we think X is conscious but not Y. As I’ve noted before, you could just say you think a dog is like us but a fish or a laptop isn’t, and you’d be expressing pretty much the same sentiment. But there’s no obvious metaphysical mystery in degrees of similarity or difference.

LikeLike

The interesting thing about intuitions and biases is that everyone has them. (It’s part of the something it is like to be human.) The real question is how well they’re grounded and what informs them.

I quite agree asking what physics accounts for the something it is like and for phenomenal experience is the same question. It’s the question I’m asking; there’s nothing circular about it; it’s a direct question. (I used the latter phrase because you earlier mentioned it was a synonym, and I completely agree.)

Red flowers and green leaves, along with hot and cold surfaces, have myriad distinguishing features, but what has that to do with what it is like for humans to experience them? The question about the emotions a red flower triggers is closer to the mark, but only repeats my question.

You keep saying it isn’t mysterious, but it does seem currently a big mystery.

I’ve said twice that I see Nagel’s phrase at a litmus test, so, yes, it is a way to get at whether X or Y is consciousness (with the proviso that we equate consciousness with there being something it is like — a proviso I’m comfortable with).

I did not say a dog is like us; I said there is something it is like to be a dog. I’m not sure there is something it is like to be a fish — there might be, but I’m inclined to doubt it. I’m quite certain there isn’t anything it is like to be a laptop or rock. (A big point Nagel was making is that the something it is like for a bat is beyond our ability to understand. I suspect that’s true of dogs as well.)

LikeLiked by 1 person

I would say recognizing a red flower or a green leaf is an example of an experience. Of course, the evidence is that any perception in the brain that can be conscious can also be unconscious, so it’s only a conscious experience if the system is focused on it at that point. In the case of the emotions they might trigger, we know that evaluative circuits running from the brainstem to the amygdala, nucleus accumbens, ventral medial PFC, and other regions are involved. All indications are it’s all neural processing (supported by glia).

LikeLike

Well, as you said above “there remain plenty of gaps in knowledge” and our understanding is “far from complete” but I have always agreed that “there’s nothing in principle indicating the answers aren’t available.”

To take this back to my original comment, Nagel’s notion that there is something it is like to be a brain — be it human, dog, or bat — speaks to an important distinction in science: It’s a notion that only applies to brains. Further, it may only apply to sufficiently advanced brains. It may not apply to fish or bugs, for instance. (Or it may; we don’t really know.)

Unless one ascribes to panpsychism, there isn’t any question whether there is something it is like to be an atom, a tectonic plate, a thunderstorm, or a clock. The question only arises with regard to brains… and putative systems we might create to emulate them.

To me the value of Nagel’s phrase is in, firstly, pointing out the differences between those two distinct classes of system, and secondly, in pointing out the differences between different kinds of brains. (I’ve spent considerable time wondering about the something it is like to be a dog, but to quote W.G. Sebald: “Men and animals regard each other across a gulf of mutual incomprehension.” Nagel’s main point was that it’s just not possible.

And I think this divide between systems for which there is something it is like to be that system, and those for which there isn’t, is what Chalmers’s “hard problem” is getting at. As I’ve said before, that there is currently no consensus on what “consciousness” even means speaks to the difficulty of the problem.

In neither case is anything mystical meant. Only that brains have an important distinction between them and all other systems we study, and that the something it is like offers a challenge unlike most challenges in science. I think that, in such light, they are simple and clear-cut and that your disdain for them is indeed misguided.

LikeLiked by 2 people

“Along those lines, the question I would have is, what does that very common phrase, “something it is like”, mean? (Other than its synonyms: subjective experience or phenomenal consciousness.)”

I’ll try to clarify it on example of seeing colors. “What does it like to see red color?” means “How does color red look?”. When robot detect color with camera, this color haven’t got any look to it. For people colors look. By the same token, for you it is like to feel pain and so on. The whole of these things constitute what does it like to be you. It is your internal movie.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Hi Konrad,

I appreciate the effort at clarification. You’re basically talking about qualia. The thing about qualia is that they’re composed of both sensory processing and affective reactions. When a color is “a look” to us, it’s the visual discrimination coupled with all the associations triggered by that discrimination. So when you see red, your brain is processing a pattern of firing patterns from your retina, which in turn trigger a vast galaxy of concepts and feelings associated with that pattern. This is our experience of “the look”. It’s why the experience of redness feels rich.

On qualia and the movie, I’ve done some posts on these.

For qualia: https://selfawarepatterns.com/2020/02/11/do-qualia-exist-depends-on-what-we-mean-by-exist/

For the movie: https://selfawarepatterns.com/2020/11/28/the-problem-with-the-theater-of-the-mind-metaphor/

The TL;DR is that the movie metaphor is problematic.

LikeLike

“When a color is “a look” to us, it’s the visual discrimination coupled with all the associations triggered by that discrimination.”

It is albo something else. There is also non-functional property of your color experience (how this color looks for you). This thing is knowed by Mary when she sees the red color at the first time. I can’t convince me that this is illusory. Event it is conceivable that external world does not exist but non-existence of non-functional property of color experience is equally inconceivable as my experience not occuring.

Even if qualia are illusory, there is internal perception of himself. It is difficult to speak about self-consciousness without this internal perception.Mere functional organisation does not cause that somebody realizes that himself exist.

LikeLiked by 1 person

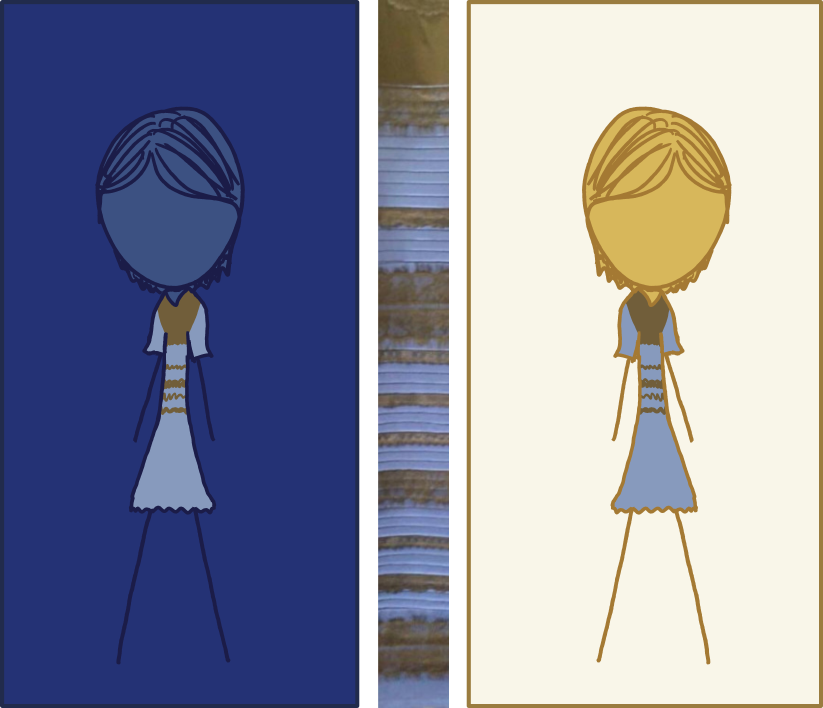

I would say the look of a color is functional, in the sense that the look of red distinguishes it from green, or any other color. Colors are an evaluation our brain makes based on the pattern of signaling from opponency cells in the retina, which in turn are stimulated by the pattern of Long, Medium, and Short wavelength receptor cones. (These are often described as red, green, and blue cones, but the matches are much less precise than that implies.)

Each color is essentially a categorization, the triggering of which is extremely complex. Which colors we see are often the result of an enormous range of factors. It very much is an evaluation of our nervous system, one that different brains don’t always reach the same conclusions on, or even the same brain at different times.

For a particularly famous example, see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_dress

For another example, the two circles at this url are the same color: https://www.sciencealert.com/here-s-why-you-re-fooled-by-this-classic-visual-illusion

Introspection is definitely real. It’s also been shown through extensive psychological research to be unreliable. This is powerfully counter-intuitive, but I think understanding that unreliability, and coming to terms with it, is the first step in understanding consciousness.

LikeLike

Yes, exactly. The personal lifetime autobiographical movie starring you!

LikeLike

“I would say the look of a color is functional, in the sense that the look of red distinguishes it from green, or any other color”

The look of red is not merely functional in the sense that look is not reduced to the causal role of color.

“Introspection is definitely real. It’s also been shown through extensive psychological research to be unreliable. This is powerfully counter-intuitive, but I think understanding that unreliability, and coming to terms with it, is the first step in understanding consciousness.”

Introspection is not reliable in every situation but some things are not possible. It is not possible that introspection indicate feeling of pain when I don’t feel antything. It is not possible that introspection indicates that I see red when I see green. Optical illusions are not introspection errors. In the case that you see green object as red, you have quale of red color. Introspection unreliably indicates this red quale.

LikeLike

What about color would you say is outside of its functional role?

LikeLike

I think I can make a reasonable case that Solms at least has a roughly correct perspective here Mike, as well as that the argument you’ve provided may be considered a bit anthropocentric.

Consider the following hypothetical situation: A human baby is born, immediately immobilized, and then hooked up to a machine which keeps it alive in isolation. Furthermore this being is also caused to feel horrible pain perpetually, though possibly permitted to sleep from time to time before it’s woken up for more such treatment. Holly shit!

The question for you here is, because it’s at least biologically a normal human, would you say that it could display any intelligence? If so then as such a non lingual and paralyzed experiencer of pain, what might an example of this intelligence be?

I’d say that this being would merely be a receptacle of suffering rather than anything intelligent. From this perspective affect exists as an input from which to potentially drive intelligence, though intelligence will not be inherent.

Theoretically before functional subjectivity existed there were simply non-conscious brains. At some point however certain brains should have done some things which caused epiphenomenal experiencers of affect, probably in the form of the right kinds of neuron produced electromagnetic fields. Furthermore at some point such experiencers must have been given the opportunity to affect organism function given their inherent desire to feel good rather than bad. Thus the evolution of a second form of computer which could display “intelligence” as we know it, and so effectively deal with more “open” circumstances that it didn’t need to specifically be programmed for. This is the serial mode of function by which existence is experienced by us, unlike the parallel mode of brain function which harbors no subjectivity.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Eric,

I would say whether the baby could display intelligence is no more relevant than whether it could display its suffering. Given that its nervous system would be receiving sensory input of some kind and performing an evaluation of that input, its system would still be doing a lot work, work we’d consider “intelligent” if it were in an ANN. It has to do that work in order for it to be aware of that evaluation, that is, to feel pain. It would be incapable of making use of that information, but only due to artificial constraints.

But I think your description of the scenario, and what you try to derive from it, is a demonstration of the intuition I discussed in the post. You’re taking the introspective impression that pain is something that happens to us, rather than a conclusion our nervous system reaches. At best it’s something that happens to the conscious us. But only after an enormous amount of preconscious processing.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I guess that’s one issue here Mike. Even if one attempts to clarify that they’re referring to “subjective intelligence”, standard watered down usage of the term may open it up to a non subjective idea.

What I’ve done here is demonstrate that affect consciousness should exist before the sort of “intelligence” that you and I display subjectively. Yes that baby’s non-conscious brain will be what creates affective states, which you might thus want to call “intelligence”, though this should be considered quite different from the “subjective intelligence” which it’s prevented from displaying in my scenario.

So maybe a compromise is possible? Here we could say that there is non-subjective intelligence associated with ANNs and so on, as well as a subjective kind which may or may not occur by means of affective states of existence as I explained above, and so what I presume Mark Solms was referring to? And note that I didn’t even exclude the possibility for subjectivity to exist when certain information is processed into other information. As you know I consider instantiation mechanism required for all events in a natural world, including subjectivity.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Eric,

I actually alluded to what you’re calling “subjective intelligence” and “non-subjective intelligence” in the post.

I’m not wild with the adjective “subjective”. It implies maybe the intelligence isn’t real. But I think we can agree that consciously enabled intelligence depends on non-conscious intelligence. It’s the non-conscious intelligence that even the unfortunate baby in your scenario would have. Although remember that I see consciousness itself as a type of intelligence. So it would still have at least glimmers of that type of intelligence, just be unable to do anything with it.

LikeLike

Which of these things is not like the others? Which of these things just doesn’t belong? (H/t: Sesame Street) Actually it’s not quite Sesame Street, as there isn’t just one answer; three of them don’t belong: biopsychism, quantum physics, and electrical fields.

Consciousness requires intelligence (of the sort that some AI researchers have worked very hard to develop for visual information processing, for example). Ok, sure, but the brain is chock full of biology, quantum fields, and electrical fields. The jury is out on the latter two doing serious intelligence heavy lifting, and definitely in on biology: it’s absolutely involved in everything the brain does. So if you grant that intelligence is vital to consciousness, then all three of these things have to be in the running. And if you don’t grant that intelligence is vital to consciousness, then that doesn’t make these three ideas more attractive.

LikeLiked by 1 person

It seems like maybe you’re replying to the literal meanings of the labels rather than the theories they refer to. There’s no doubt that biology is involved in animal consciousness, since all animals are biological. Likewise, there’s also no doubt that quantum physics is involved, because it’s involved in everything. And of course an electrical field is involved in moving ions across the neural membrane in an action potential.

But those aren’t what the referred theories are asserting. They’re asserting either than all life is conscious, or that only life, in principle, can ever be conscious. Or that quantum effects are involved in a way they’re not involved in every other physical process (and in a manner that requires new physics). Or that neurons communicate with each other through EM fields (other than through electrical synapses). Any of these could conceivably be true, but they’re not propositions driven by the data, just speculative guessing people try to fit into the current gaps in the data.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Take the idea that all life is conscious. Well, all life does a fair amount of computing, in some fairly straightforward sense of the term. Proteins, enzymes, RNA strands are directed where they need to go. So this kind of biopsychic could take your discussion here as evidence in favor of their hypothesis.

Quantum entanglement could serve computational functions, at least in some broader definition of computing than the Church-Turing one, and probably in that narrow sense as well. And electrical fields on a many-neuron scale, likewise. Indeed, advocates of the larger-scale electrical fields claim as much.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Okay, here’s my take:

“But it does imply that consciousness is a type of intelligence”

This is backwards, cart before horse. I say consciousness is information processing (specifically defined), and intelligence is a measure of sophistication of information processing. Thus, intelligence is a measure of the sophistication (phi?) of consciousness.

I appreciate that you, Mike, will invoke “the eye of the beholder”, and that you require a level of sophisticated information processing of which humans are certainly capable and other entities might be capable. But then your project becomes determining the specific features of that information processing which is necessary and sufficient, and then deciding what other entities may have that. I suggest that this project is like trying to figure out what a “computer” is by starting with Watson, and then trying to decide if my old Apple IIc is a “computer”, allowing the conclusion that the IIc is not a computer because it has no means to connect to the internet and thus cannot consult Wikipedia. Whether something is a “computer” is in the eye of the beholder.

*

[so there]

LikeLiked by 1 person

Well, we could substitute “information processing” everywhere I used “intelligence” in my statement about the relationship between the two. I’m not sure we’re doing much other than semantic chair rearranging though.

Identifying intelligence with phi is interesting. But I think Christof Koch would strongly disagree. He’d point out that a computer system can show considerable intelligence while having zero (or very low) phi. I think he’s a strong advocate for consciousness being separate from intelligence.

It is worth noting that the visual cortices that perform all the work that eventually results in our visual awareness do have a substantial phi associated with them. But the actual IIT has its exclusion postulate that requires we focus on phi-max. (There’s a new paper exploring problems with phi, which I haven’t had a chance to read. Don’t know if I will. I’m not sure if IIT is worth the time anymore.)

On your “computer” analogy, I take it you think I’m saddling consciousness with too many requirements. Maybe I am. It depends on our definitions. When someone proposes a very liberal definition of consciousness, all I can do is point out what’s missing and what it includes in club consciousness. When they propose a very sophisticated version, all I can do is point out what gets excluded. We all have to decide where on that spectrum our intuition of a conscious system is satisfied. (“Eye of the beholder” indeed!)

[so there back 😉 ]

LikeLike

Hmmm. To clarify:

First, referring to phi was being a bit flippant. In no way do I think phi is identified with intelligence. Although I will say that higher intelligence implies higher phi, but not vice versa. [While writing the previous post, I was this close to talking about intelligence as more soPHIsticated info. proc.]

Second, I don’t really mean to equate consciousness with information processing except as to say that information processing is the basic unit of consciousness. When people ascribe some small amount of consciousness to bacteria, they are more or less referring to information processing. When people refer to the “what it’s like-ness” of human consciousness, they’re basically referring to results of certain very sophisticated information processing. Ditto for predictive processing, higher order thought, global workspace, what have you.

*

[still trying to figure out exactly how info. processing can be done via electronic brain waves]

[and while I have your attention, don’t know if you’re interested in the neurolink stuff, but here is a good (~ 30 min.) video explaining where it’s at now: https://www.youtube.com/embed/rzNOuJIzk2E%5D

LikeLike

Ah, thanks for the clarification. I guess I took it much too seriously.

I agree that information processing is the meat and potatoes of consciousness. (I think the same thing of intelligence.) And that a lot of what inclines people to say that a bacteria is conscious is its information processing.

The “what it’s like-ness” point is interesting. I’m not sure too many people who use that phrase would necessarily agree with you, at least not without elaboration. For example, Chalmers might agree, but he’d likely stipulate what he sees as the dual aspect nature of information, implying that information has inherent experential qualities. But I think that’s different from what cognitive theories (GWT, HOTT, etc) propose, that experential qualities are composed of information.

Thanks for the neuralink video! I’ll try to watch it. I did see the news release and a shorter video about the monkey playing pong with its mind.

LikeLike

Just so ya know, the “what it’s like” explanation involves unitrackers, aka, pattern recognition units. I’m still trying to work up the best way to ‘splain it, but I keep wanting to start with “Okay, you’re in the Chinese room …” and then I think better of it.

Real short version: If you have a system with X unitrackers, to that system, everything is “like” one or some combination of those unitrackers turning “on”, or it’s not like anything. When Mary sees red, she learns which unitracker she has for red, but can only reference it by saying “the unitracker that turns on when I see red.” [That is, until we put in the neurolinks and track down the specific one. :). ]

*

LikeLike

Yes, please just walk away from the Chinese room temptation. 🙂

I just finished discussing redness with someone. I think red has to be far more than just one unitracker. It seems much more likely to be a vast galaxy of unitrackers, all triggered by certain patterns of activation coming in from the retina.

LikeLike

I didn’t mean to suggest that unitrackers were independent, and I didn’t mean to suggest you have only one for red, except you probably do have one for red which is connected to fire-engine red and cherry red and rose red. I expect there is feed forward and feedback among them. And you repurpose them when you learn. You can go from having one for the taste of “red wine” to having ones for “smoky tannins”, “grassy finish”, etc. And you can repurpose the ones for colors to get more nuance from sounds (if the color ones aren’t being used).

I’m really getting convinced that cortical minicolumn = unitracker. Keeping my eyes out for evidence one way or another.

*

LikeLiked by 1 person

I tend to think minicolumns are more of a ontogeny thing rather than a functional one. It seems like there might be numerous unitrackers within a column, and that some might have “territory” in multiple columns. But maybe the physical topology imposes a functional topology.

Looking for evidence (or counter-evidence) is the way to do it!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’ve always felt the two terms to be different but somewhat related. However, that much discussion goes on with both terms without precise definitions. I’ve noted elsewhere that it is difficult, for example, to find a definition of “intelligence” in Nick Bostrom’s book on SuperIntelligence :).

I’ve considered (probably in contrast to many people) that intelligence can arise in nature without consciousness. I don’t consider slime molds conscious, but I do think they are intelligent. I think evolution itself is somewhat of an “intelligent” process. The intuitions of intelligent design believers are right. I think they are just wrong about the need for a Designer. Darwinism itself produces quasi-optimal solutions and complexity through evolutionary processes. A foot in a mammal evolving to live in the water gradually becomes webbed and eventually a fin. Slime molds though means not totally understood can form themselves to “solve” mazes and find shortest paths to nutrients.

Consciousness is extension of evolutionary intelligence. To create quasi-optimal solutions and complexity in living organisms in real time, complex learning is required. Hence, consciousness is highly associated with the learning process as posited by Simona Ginsburg and Eva Jablonka and others.

LikeLiked by 1 person

James, I agree with everything you write here. (Well, I’ve never read Bostrom’s book, but based on his presentations, I can see him never actually defining intelligence.)

I’ve always been struck by the seeming creativity that evolution displays in solving adaptation problems. Biologists often talk about species “coming up with innovations” when referring to capabilities they evolved. It’s a natural way of describing things, although I’ve encountered creationists and IDers who misunderstood what they were saying, so it requires understanding natural selection and the level that the innovations are taking place at. But avoiding that kind of language takes so much pedantic work that it’s better to just periodically clarify.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Animals have the capacity to assess a posteriori evidence or they would not survive as a species. This skill set could be considered intelligence which it is, but that intelligence is restrained and limited by the five senses. I would say that meaningful intelligence is twofold: First, it has the capacity to overcome the self-imposed limitations of our own confirmational biases and secondly, it is intelligence that transcends empirical limitations, an intelligence that would be a measure of one’s ability to draw “correct conclusions” based solely upon a priori and synthetic a priori analysis.

A priori and synthetic a priori judgements are almost like “spooky action at a distance”. They are long range skill sets, capabilities that are acute; and those skill sets are much more reliable that a posteriori judgements. They are skill sets that go beyond the necessity of mere survival alone and open the door to the underlying nature of reality and ourselves. As a species, homo sapiens have not evolved to the point to where this type of intelligence is the norm. It does exist within the species, but it is very rare indeed.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I think I understand what you’re saying here about animals Lee. I would just note that I think animals do have limited reasoning abilities, so some limited non-symbolic a priori reasoning. It’s just that human do have symbolic thought, allowing our reasoning to go much further. Michio Kaku, in a recent interview, remarked that we can’t teach our pets the meaning of tomorrow, while humans often live in our tomorrows.

On being able to see the underlying nature of reality and it being very rare, maybe. The problem is that many people have concluded they are the ones that have that. But others have also reached a similar conclusion, but with different answers. How do we figure out who is right and who is wrong? Ultimately, our a priori explanations need to predict empirical observation. In other words, the a priori must reconcile with the a posteriori. The ones whose models do that, may be closer to the truth, or at least less wrong.

LikeLike

“How do we figure out who is right and who is wrong?”

There is no “we” in that assessment Mike, there is only the one who knows and that a priori state of “knowing” is not transferable from one person to another. So you can rest assured that any and all of the new age gurus the likes of Rupert Spira and Deepak Chopra are just modern day snake oil salesmen.

LikeLiked by 1 person

My god, I can certainly relate to that: “[Rupert Spira and] Deepak Chopra are just modern day snake oil salesmen.”

LikeLike

I’m with you on Chopra. I don’t know enough about Spira to say one way or another. Googling him gets a lot of New Agey stuff, which is not my cup of tea, but it wasn’t immediately clear he’s the shyster Chopra is, but I’ll admit I didn’t spend much effort on it.

LikeLike

“Ultimately, our a priori explanations need to predict empirical observation. In other words, the a priori must reconcile with the a posteriori.”

Ultimately is the right context to frame your compelling assessment Mike. But we seem to forget, simply do not understand or conveniently choose to dismiss that “ultimately”, only a priori knowledge can lead to the type of understanding that will resolve the hard problem of matter and the hard problem of consciousness. And that “ultimate criteria” is “intelligent” logical consistency where a predictive model based solely upon a priori intuition is developed, one that can be intellectually verified through thought experiments alone to be 100% inclusive, one that has no exceptions or contradictions for any and all systems throughout all of time.

A posteriori analysis does not have that capability nor does it have the reach to accomplish that goal because it is limited to the five senses; and due to that constraint alone, there will always be a possibility that an exception or contradiction will be found in any scientifically developed empirical model. A further evolutionary advancement of the species is necessary to achieve this capability. And when that species arrives on the world stage it will encounter the same restraints that exist between species in general; and that restraint is communication. This species will be able to effectively communicate with each other but they will not be able to convey what they “know” with the Cartesian Me species any more than a Cartesian Me can convey the idea of tomorrow with a dog.

Maybe the Cartesian Me species are all philosophical zombies??????? 😟

LikeLike

Lee, this seems like the old rationalism vs empiricism debate. History seems to show that we need both. Any attempt to only use empirical data (which gets us close to logical positivism) or armchair rationalism, is too narrow, giving up too many tools. It seems like a circle, making observations, theorizing about those observations, testing the theories with new observations, adjusting theories, new observations, etc. We have to look at the world to learn about it, but all observation is theory laden.

The possibility that we’re all philosophical zombies that compute we’re something more, is one that doesn’t get discussed often enough. 🙂

LikeLike

“The possibility that we’re all philosophical zombies that compute we’re something more, is one that doesn’t get discussed often enough.”

It is somewhat amusing to think about it that way. I mean after all, we are all just ” dead men walking”. I can’t help but think of Jordan Peterson who views our existential existence as a tragedy. Jordan is a relatively recent inspirational speaker to arrive the world stage. His views catch a lot of flack from the more trendy new agers.

LikeLike

Peterson is another one I’m not that familiar with. Most of what I’ve heard is from liberals unhappy with something he said. Although someone did comment a while back about his theory of truth, which sounded pragmatic, along the lines of William James.

LikeLike

Jordan Peterson is very pragmatic, I’m sure you would like him. His book “12 Rules for Life” has rule number one (1) as: “stand up straight with your shoulders back.”

LikeLiked by 1 person

Lee,

I’m a little dubious of this :”based solely upon a priori and synthetic a priori analysis.”

That is to say, I am not convinced that it actually exists.

What is the evolutionary origin of this? Isn’t it just something else acquired bottom-up and possibly subject to different but similar limitations?

I’m not an expert on Kant but I’m guessing this is coming from him.

LikeLike

James,

You’ve spent enough time on Kastrup’s blog site to know that idealism is a dead horse that continues to be flagellated. So if you are looking for an evolutionary origin for a priori and synthetic a priori representations, one must be compelled to consider what matter is in and of itself. Not only what it is in and of itself, but its origin; fair enough…..

You are right, it does come from Kant. Kant was a genius in his own time but his ontology is incomplete. What is not incomplete is his fundamental assumption that; “although we are denied complete understanding of the ‘thing-in-itself’ we can look to it as the ’cause’ beyond ourselves for the representations that occur within us”, regardless of whether those representations are empirically acquired through the five senses or a priori representations that are acquired through intuitional insights. So if you are dubious that a priori and synthetic a priori representations exist you must be equally dubious that a empirical representations exists. That is of course, unless you think Kant was full of shit.😎

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m not why you brought the Kastrup blog into the discussion.

I’m okay with the idea that our sensory representations are just that -representations. They have arisen for their ease of use and their utility for survival and acting in the world, not for their fidelity to some out there reality. But why would the a priori representations be different? They might be if they really were a priori but that is precisely what I am doubting. I’m suggesting they arose as second order abstractions for the same evolutionary utilitarian reasons that sensory representations have arisen. In other words, they really are a posteriori . Nothing is acquired independently from experience, although by experience we need to the entire evolutionary history of organism.

Where that puts in regard to Kant I don’t know. 🙂

LikeLike

“They have arisen for their ease of use and their utility for survival and acting in the world, not for their fidelity to some out there reality.”

Absolutely…..

“I’m suggesting they arose as second order abstractions for the same evolutionary utilitarian reasons that sensory representations have arisen.”

I do not dispute that aspect either. Nevertheless, are we as the top predatory species on the planet arrogant enough to believe that the evolutionary process has reached the apex of its capability? And if not, what would the next evolutionary level of experience look like? Would it be that the new species is now equipped with the intelligence, an intelligence that enhances the utility of logic to explore that underlying reality which drives the species? Now you personally may not be interested in that quest, and that position is perfectly acceptable.

“Nothing is acquired independently from experience,”

That’s the point I tried to express in my original reply to Mike; a priori representations are themselves experiences, very personal and private experiences, experiences that convey meaning beyond the scope of the five senses. It is the meaning of those experiences that are not transferable. The utility of meaning obtained through a priori representations can only be shared when another individual has the exact same experience.

I am in agreement with Kant that a priori representations and a posteriori representations are not different versions of the same thing. One can reach out and touch, see, hear, smell and taste a posteriori representations and one can equally weigh, measure, test and place in a haldron collider a posteriori representations. A priori representations only exist in the quantum system we call mind. In that light, one is now once again compelled to consider: Is the fundamental nature of reality matter, or is it mind?

LikeLiked by 1 person

“Nevertheless, are we as the top predatory species on the planet arrogant enough to believe that the evolutionary process has reached the apex of its capability? And if not, what would the next evolutionary level of experience look like? Would it be that the new species is now equipped with the intelligence, an intelligence that enhances the utility of logic to explore that underlying reality which drives the species? Now you personally may not be interested in that quest, and that position is perfectly acceptable”.

Definitely interested in that question.

LikeLike

Although I am not a property dualist (I think I’d rather be a full epistemological or metaphysical idealist), Chalmers was not wrong in separating p-consciousness from the “easy problems,” which are related to a-consciousness.

This distinction was made by Ned Block when he stated that a-consciousness is the functional aspect of the mind while p-consciousness is its experiential or phenomenal aspect. One can conceive of a completely functional mind lacking phenomenality the same way one observes an ANN as being completely functional without having phenomenal experiences.

Whatever the answer might be to the HPOC, I think it might probably require abandoning metaphysical functionalism.

As long as talk of minds is done in terms of functions, states, and events, disregarding its phenomenal aspect, we will probably never get rid of this problem.

LikeLiked by 2 people

You could be right, but obviously I disagree. I think Block’s move, treating phenomenal consciousness as something separate and apart from access consciousness, actually turns a complex galaxy of scientific problems into an intractable metaphysical mystery.

For me, it’s like trying to understand how a car works, but ruling out any discussion of engines, fuel lines, axles, transmissions, break pads, etc. If we insist none of that has anything to do with how the car allows the driver to get to places, then its function becomes a deep, perhaps intractable mystery. But it’s a mystery we’ve manufactured.

I think it’s much more productive to accept that phenomenal consciousness is access consciousness. They are one and the same, just viewed from different perspectives, one from the inside, the other from the outside. The access mechanics are the internal mechanisms of phenomenality. The only reason we have the impression they’re different is due to the unreliable nature of introspection.

But maybe I’m wrong. If so, then we might be looking at panpsychism or idealism to explain phenomenal consciousness, because the science doesn’t currently indicate there’s anything exotic about the physics in the brain.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I have a horrible and uncomfortable suspicion that you might be right. That consciousness is an illusion generated from bodily processes and that we are prediction machines with memory. Partly that seems to be what even the dear old Buddhists have told us for 2,500 years.

I don’t know whether you have ever read, watched or listened to Robert Sapolski – the biologist and neuroscientist from Stanford. I find him fascinating, convincing and immensely likeable. Partly because I agree with his view on society and our shocking capitalist economy.

In any event he is a pure determinist and admits to finding his conclusions depressing. I believe he also suffers from depression, reading between the lines.

The lack of free will makes it difficult in a way to understand change in society and human behaviour. And animal behaviour in general. Nevertheless I can appreciate the argument.

I think, therefor I am. Or perhaps not. Who or what is writing this response to you? A jumble of atoms and subatomic particles it seems.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m not on board with saying consciousness is an illusion. I prefer to describe it as emergent. It’s really the same ontology, but “illusion” is too eliminativist, and makes too many people view the proposition with the same horror you do. Regarding it as emergent seems less cold and spartan in our ontology.

I’m a fan of Sapolski. I actually started to read his book a while back, but got distracted. At some point I need to swing back around to it. He’s a pretty hard core, particularly in being a free will skeptic. I agree he manages to convey it in a likable manner. Thanks for reminding me!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Just a few thoughts Mike.

“The definitions for both concepts are controversial.”

We can’t say clearly what the word consciousness means and we can’t clearly say what the word intelligence means, so the two are surely related. Which reminds me that consciousness and quantum physics are both mysterious so consciousness must be produced by quantum effects. Impressive logics, yes?

If IQ tests are measuring what we call intelligence then intelligence must be “pattern recognition and pattern matching.” Higher intelligence would be more skillful pattern recognition/matching across multiple domains. By the way, that pattern matching is done unconsciously and we have no conscious access to it.

You ask, “… what distinguishes [consciousness and intelligence] from each other?”

I’d say that intelligence as pattern recognition/matching contributes mightily to the contents of consciousness but since consciousness is a simulation in feelings of an organism centered in a world, consciousness is not a type of intelligence.

BTW, I don’t know why biopsychism appears in your sentence with panpsychism and dualism. The first Google hit for a biopsychism article explains that:

“In 1892 Ernst Haeckel coined the term ‘biopsychism’ to refer to the position that feeling is ‘a vital activity of all organisms.’ … In contemporary terms, biopsychism can be described as the thesis that all and only living systems are sentient.”

Wikipedia’s Sentience article says:

“Sentience is the capacity to be aware of feelings and sensations. The word was first coined by philosophers in the 1630s for the concept of an ability to feel, derived from Latin sentientem (a feeling) … .”

While I disagree with the ‘all’ in Haeckel’s “all organisms” it seems obvious that feelings are a biological phenomenon and biopsychism is a reasonable position, unlike panpsychism and the like.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Stephen,

That’s not the logic I use in the post. If you think it is, I hope you’ll consider looking at it again.

Interesting idea on consciousness being pattern recognition. I think that’s part of it, particularly for the preconscious portions of perception. But I’m not sure it fits for simulating action scenarios, or figuring out a complex navigation. I guess you could stretch it to fit those cases, but it feels too simple.

I know we’ve discussed this before, but I’m still not clear what “simulation in feelings” means.

I listed biopsychism because it asserts either that 1) all life is conscious, or 2) only life can ever be conscious. 1) only seems true only if we take a very liberal conception of consciousness. It’s not as liberal as panpsychism, but it’s still extremely liberal. 2) strikes me as a very strong statement, one I think isn’t warranted, unless we make it true by definition.

LikeLike

I realize that’s not the logic you used. I was trying to draw attention to the great amount of theorizing that takes place in the absence of shared precise definitions of the terminology being discussed. It’s no wonder that confusion reigns.

I didn’t claim that consciousness is pattern recognition but that intelligence is fundamentally rooted in pattern recognition/matching. That’s also what underlies the ‘prediction’ (I prefer ‘expectation’) you talk about. Incoming sensory information is continuously processed as a story and an ongoing comparison with remembered stories results in the formulation of expectations. We generally experience what we expect to experience based on this mechanism. All of this, of course, is strictly unconscious processing—we do not consciously simulate action scenarios or resolve complex navigation as you sometimes seem to imply.

As regards biopsychism, I also disagreed with the ‘all’ in Haeckel’s “all organisms.” I believe he would agree that biological feelings are the only kind of feelings that exist. That’s consistent with all of our observations, which is why I believe that biological is definitional. A single counterinstance would be sufficient to establish that feelings are not necessarily biological, but no single counterinstance has ever been confidently observed. We can only properly define both sensory and emotional feelings by example so I’m curious how those who want them to be non-biological would define a single non-biological feeling. Would you (or Eric if he reads this) care to propose a definition of a single non-biological feeling?

“I’m still not clear what ‘simulation in feelings’ means.”

You’re referring to my definition of consciousness as a streaming biological simulation in feelings of an organism centered in a world. To explain, I’ll start with saying that a simulation is a representation. A simulation of weather, for instance, is a computerized mathematical representation of weather but no one would confuse it with the weather itself.

The contents of consciousness are feelings which are representations of sensory events (physical feelings) and neurobiological states (emotional feelings). The two easiest to understand are sight and sound. From my “The Consequences of Eternalism”:

“The external world contains an ocean of energetic photons, some of which enter our eyeballs and are absorbed by molecules which then change in shape and ultimately create signals transmitted to the brain by neurons. But we don’t see photons or differing wavelengths of light—photons and wavelengths don’t look like anything. Instead, the brain’s processing creates and ‘displays’ the familiar colorful visual world. Sound, too, doesn’t exist in the world. The external world contains waves of pressure propagating through gases, liquids and solids, some of which enter the ear, vibrating the eardrum and other structures that ultimately create neuron-transmitted signals sent to the brain. But, as with vision and photons, we don’t hear sound waves. The external world, including that room you believe is pulsating with the sound of your favorite music, is completely silent.”

So, what we see and what we hear are representations of photons and differing wavelengths and representations of compression waves. These representations are feelings—you know the feeling of seeing the color green and you know the feeling of hearing a singing voice. “Representation in feelings” and “simulation in feelings” are the same.

But, unlike a simulation of weather, which no one would confuse it with weather itself, the simulation in feelings of our experience is completely and literally taken as the actuality of ourselves centered in the world. We externalize it all, from believing that a rose is actually red and the world is a noisy place. We further externalize the streaming nature of consciousness itself as a flowing time in the world—a flowing time that doesn’t exist.

Have I cleared up what I mean by “simulation in feelings”?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Stephen. I had forgotten about the way you use “feeling”.

In terms of your question about examples of non-biological feelings, in the sense you use the word, what would you say distinguishes the sensory representation in a brain from the representations in a self driving car that it builds from its various sensory apparatus (lidar, cameras, etc) and uses for navigating the road?

https://www.businessinsider.com/how-googles-self-driving-cars-see-the-world-2015-10

LikeLike

Sensory | ˈsensərē |

adjective

relating to sensation or the physical senses; transmitted or perceived by the senses: sensory input.

Mike,

I’m not sure how Stephen will respond to your post, but the use and application of the word sensory in your self-driving car example is misplaced and therefore should not be used….😎

LikeLike

How so Lee?

LikeLiked by 1 person

I guess it is whether you consider that physical senses and sensations can be non-biological. I wouldn’t engage in a semantic argument about it but acknowledge that various electromechanical devices can act like senses. That still leaves open whether there is anything remotely like phenomenal consciousness is happening somewhere in the car.

LikeLiked by 1 person

That’s why I quoted the dictionary Mike. Now, do you really believe that the New Oxford American Dictionary was referring to anything thing other then the five senses of human experience in its definition of “sensory”? If these word games concerning consciousness are all about moving the goal post every time somebody is expressing a point, then it’s just a game. You keep claiming that consciousness is in the “eye of the beholder” and unfortunately this is a tactic of the game. But if one is genuinely interested in establishing base line definitions for genuine edification, then we should resort the kiss principle: “keep it simple stupid”. For example:

Consciousness: noun

Together to know us; a state of being. Consciousness is derived from the Latin root words Con, (together); Scio, (to know); Us, (us) and Ness, ( a state of being). Conscious means; together to know us; Ness means; a state of being;

Notes:

The meaning of consciousness is derived from its Greek origin, a philosophy based upon the anthropocentric principle of Protagoras of Abdera; a manifesto which declares that “Man is the measure of all things.” Since the time of the Greeks, man and man’s experience of consciousness has become the standard by which everything else is adjudicated to be conscious or not. ThIs discrete definition of consciousness is limited and restrained therefore, the term cannot be used for anything other than a comparison to the human experience. If the human experience itself is the standard by which all other systems are judged to be conscious, then those systems will be limited and few.

Nothing wrong with discussing what that experience entails and Stephen’s point is narrowly focused on that experience.

LikeLike

James,

Since consciousness by definition is limited to the system of mind then no, there is not anything remotely happening like phenomenal consciousness in the car.

If you read my previous post you should be able to extrapolate that the only thing happening in the car are the valences of the nuclear force both strong and weak, electromagnetism, and the attraction of gravity, all of which are non-conceptual “representations” of value, representations that do not require any form of awareness or cognitive function in order to be felt.

Grab a magnet and an iron nail and play with them on your kitchen table, then you can decide if the reason the nail moves to the magnet is because of valences. The nail is not aware of the feeling that causes it to move toward the magnet because it has no cognitive function or awareness, but the feeling of this thing called electromagnetism exists nevertheless, and that feeling is a valence, which is a non-conceptual “representation” of value. It’s all about “representations” James.

LikeLike

I have no idea what the lexicographer who wrote that entry had in mind Lee, but I do know a lot of technology fits what they did write. “Keep it simple stupid” has its uses, but not when it’s used in an attempt to shut down any challenges to our biases.

My question was, given the description of consciousness provided involving representations used in simulations, what is missing in the car? (I definitely think there is a difference. See my hierarchy posts. But this isn’t about my view.)

LikeLike

Lee,

I think you are being a little too pedantic in your point.

We all know that sensors

sensor

noun

a device which detects or measures a physical property and records, indicates, or otherwise responds

sensor (n.)

1947, from an adjective (1865), a shortened form of sensory (q.v.).

has the same derivation as sensory but are not the same as biological eyes and ears.

LikeLike

Mike,

My reference to “kiss” is not intended to shut down any challenges to your biases or anyone else. Kiss is simply a technique intended to be more “pedantic” as James would say. I think being concise in the use of our definitions is necessary so when I state to a fellow Cartesian Me that I “sense” the impending doom of American culture I will not get a response such as: “Dude, are you talking about a device which detects or measures a physical property and records, indicates, or otherwise responds…..

Seriously guys????????????

LikeLike

Mike, it’s certainly possible for a device to compute itself centered in a world but that’s completely different from an organism feeling itself centered in a world.

Consider Commander Data of Start Trek fame. It continuously computes itself centered in a world but repeats several times in the series that it cannot feel anything. The writers of the show demonstrated their bias in understanding feelings as emotional feelings only, neglecting physical feelings (like touch for instance). Note that when Data acquires the ‘feeling’ upgrade chip it always goes off the wall emotionally and never comments about physical feelings at all, unless I missed an episode.

It’s interesting to contemplate whether we would have a moral relationship with a device that computes itself centered in a world since damage to itself would be computed rather than felt as pain. Another topic … another day.

LikeLike

Stephen, Star Trek is something of a mess when it comes to the mind, implying that a purely logical being is a coherent concept. But if we pay attention to Data’s behavior, he has preferences and is motivated to do things all the time. He springs into action when one of his crewmates is threatened. He takes care of his pet cat, Spot. And he clearly prefers survival when an AI specialist wants to dissemble him to figure out how he works. (The AI specialist also refers to him as “it” in the episode: “The Measure of a Man”. It’s worth noting that Data apparently has male equipment, having sexual relations with at least a couple of female crew members.)