I usually have to wait for the audio version of these Mind Chat podcasts, but this one seemed a reasonable length and I had some time this weekend. Keith Frankish, an illusionist, and Philip Goff, a panpsychist, interviewed Noam Chomsky for his views on consciousness. (The video is about 72 minutes. You don’t necessarily need to watch it to follow the rest of the post.)

I posted a while back on a document that Noam Chomsky has on his website which discusses his views on mysterianism, the idea that some things are beyond human comprehension. Chomsky touches on consciousness a bit in that document. At the time, I came away with the vague impression that he was an idealist of some kind, someone who takes reality to be primarily mental.

However, in this interview he seems to question the existence of the hard problem of consciousness, a common conclusion for reductive physicalists, but also to endorse Russellian monism, often seen as a variant of panpsychism (as David Chalmers, with some puzzlement, noted in a tweet.) During the interview, Goff gives Chomsky a sales pitch for panpsychism (24 minute mark) and Frankish for illusionism (42 minute mark). Afterward, Chomsky seems to imply (56 minute mark) that both views could be reframed and reconciled.

I’ve noted many times that most philosophical debates are definitional in nature, and wondered on numerous occasions if this isn’t the case between illusionists and panpsychists. Maybe the distinctions amount to a verbal dispute. A certain type of naturalistic panpsychism can be seen as essentially a poetic way of describing physicalism. But most panpsychists I know draw a strong distinction between their view and physicalism.

However since what Chomsky actually talked about was Russellian monism, and because I’d never read much about it, I decided to check into it specifically. My primary source here is Derk Pereboom’s SEP article.

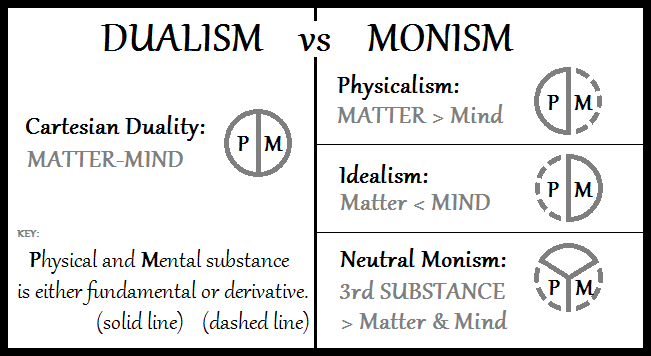

First, a quick review. Dualism is the view that there is both a mental and physical reality. Physicalism is the view that it’s all physical, including the mental. Idealism is the view that it’s all mental, including the outside world. “Neutral monism” is a term coined by Bertrand Russell for a view that reality is either a third substance, or that the distinction between mental and physical is artificial. (Russell didn’t invent the view. It’s reportedly a variant of William James’ radical empiricism.)

Apparently there are different variants of Russellian monism. Russell seems to have worked his way through multiple versions over his career, and of course there are many interpretations of those views. But Pereboom identifies three crucial theses which seem to be common throughout.

- Structuralism about physics

- Realism about quiddities

- Quidditism about consciousness

The first thesis simply says that what physics describes are the extrinsic properties of matter and energy, essentially what it does, its structure and relations, rather than what it is. It says nothing about what matter is, about what it’s intrinsic properties, its quiddities, might be. We’ve discussed this distinction before when talking about structural realism. As a structural realist, I’m on board with this one.

The second thesis says that quiddities, intrinsic properties, are real. As an epistemic rather than ontic structural realist, I’m open to the possibility that they could be real. However, if they are real, they seem like things we can never know anything about, since knowing would require interactions, extrinsic relations of some sort. Which doesn’t seem to give us much to figure out their putative nature.

So I’m leery of the third thesis, that consciousness is composed of quiddities. But I can see the line of reasoning. If someone is convinced of the hard problem, that consciousness cannot be explained by standard physics with its structure and relations, then quiddities might seem like a necessity. And maybe these quiddities would interact with each other in a completely separate framework from the standard physical one.

This view seems more like panprotopsychism rather than panpsychism. Ironically, panprotopsychism is reductive in nature, but the reduction only happens on the mental side. If I understand the Russellian view, the phenomenal properties of consciousness are composed of paraphenomenal or protophenomenal properties, which are quiddities.

But if someone has ruled out the hard problem, as Chomsky appears to do, then the motivation for thinking that consciousness is composed of quiddities seems to disappear. The quiddities become an unmotivated assumption.

Although Chomsky’s specific reason for ruling out the hard problem, that the questions being asked are meaningless, might matter here. It may mean that he actually retains some version of the hard problem, which would fit with his previous discussion of mysterianism. (Chomsky actually refers to the “hard question” in the video, which may be intentional.)

So his motivation for that dismissal and its scope may be less than an illusionist’s. Illusionists reason that introspection is no more reliable than outward facing perception, meaning what it tells us is probably wrong in some cases, including impressions leading us to think that conscious experience can’t be reconciled with standard physics. Chomsky’s concern about meaningful questions resonates with this, but I could see a line of reasoning where it could exist without the illusionist’s more comprehensive dismissal.

Alternatively, we might fully dismiss the hard problem, but regard the quiddities as components of the illusion, maybe as useful fictions. But I’m not sure that’s compatible with the second thesis above. It might come down to how loose we want to be with the term “real”. Maybe “useful fictions” should be regarded as real in some pragmatic sense. But then the question is, how is the quiddity concept useful? It also implies that something might be real for some purposes but not others.

What do you think? Can these outlooks really be reconciled? Or is Chomsky holding some view that isn’t really either of them? Or am I missing something else here?

“If I understand the Russellian view, the phenomenal properties of consciousness are composed of paraphenomenal or protophenomenal properties, which are quiddities.”

Russelian monist can be panpsychist and think that consciousness of macroscopic beings is composed from consciousness of microscopic beings.

LikeLiked by 2 people

I think that’s a common interpretation. But as I understand it, the standard Russellian view avoids the combination problem by seeing the composition as coming from those protoconscious components, rather than microscopic consciousnesses. Of course, these could be seen as definitional variations.

That said, I’m talking about a view I don’t hold, so may well be missing ingredients.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hey Mike,

I don’t think RM solves the combination problem, where did you happen to read that if I may ask? And I understand RM the same as Konrad, as compatible with either proto-phenomenal micro-components or regular phenomenal components. The combination problem is really just pointing out that we seem to have phenomenal evidence that we exist as subjects (meaning that certain phenomenal states, like my visual and auditory states go together, but others, like my visual and your auditory states, aren’t unified in the same way), and yet this fact of phenomenal subject unification is not accounted for in panpsychism as a weakly emergent phenomenon. You can spell out all the micro-facts about proto-phenomenal micro-consciousness, but you still won’t have told us what types of consciousness will be unified/composed together. RM, either proto-phenomenal, or phenomenal, just tells us what certain physical states are (what their phenomenal character is like).

Of course, there are physical/relational facts that explain the existence of physical subjects, like my body and brain, but under RM, such facts only explain how the intrinsic states are related, and not how they are composed. In other words, it seems like we could have a bunch of micro-subjects each experiencing a small part of what the current Alex experiences (but which still share some physical relation), instead of there being one macro-subject (me) experiencing the entire thing. Either scenario seems compatible with RM, so RM can’t be said to solve the combination problem.

To solve the issue, we could always add in extra rules (if certain phenomenal states y are in physical relations x, then they will combine into phenomenal states z), but the problem is that it unfortunately negates the entire point of RM and panpsychism, which was to explain our conscious reality without the need to invoke strongly emergent rules like the traditional dualists do.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Hey Alex,

You’re right. RM doesn’t solve the combination problem. My bad. I was going off the fact that its response to the combination problem is different than stand panpsychism (at least according to the Wikipedia on neutral monism). But I should have gone back and refreshed my memory before making the reply above.

I’ll defer to your knowledge on all the strengths and weaknesses of the various options. I can’t say I’m well read on panpsychist or Russellian monism literature.

LikeLiked by 1 person

No worries, it’s a very easy and understandable mistake to think. The main point of proto-phenomenal RM is actually to limit consciousness to certain structures, like animals and humans, for those more chauvinistic (shall we say) persons who don’t prefer things like rocks to have some forms of consciousness. It’s very easy to interpret this attempt to limit consciousness as a way to constrain the combination problem, but they are not actually the same thing. The former still has to introduce some rules that govern the transition from proto-phenomenal to phenomenal states, hence the combination problem. Indeed in some ways therefore, the problem is worse for proto-phenomenal RM.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks. Yeah, the distinction between proto-phenomenal properties vs phenomenal properties of smaller entities seems exceedingly academic and theoretical. And as someone is pushing me somewhere else in this thread, at some point you have to wonder what exactly this framework is providing over just plain old reductive physicalism.

LikeLike

That Russellian monism is either panpsychism or panprotopsychism fits with what I’ve heard. But interestingly, I think even the most hardcore physicalist can count themselves as panprotopsychists. After all, human beings are composed of quantum fields, according to our best physics. And so is the most inert thing you can think of, e.g. a rock. Take enough rocks, rearrange the quantum fields, and you can compose some human beings.

I’m going to wait for the audio version before I listen to this Mindchat. But on another occasion I heard Chomsky say something like: the mind-matter problem is a pseudoproblem because “matter”, as traditionally conceived, doesn’t exist.

LikeLiked by 2 people

As I understand it, a key thesis of panprotopsychism is that the reduction isn’t to standard physics, but only in terms of more primitive experiential properties. Those properties are supposed to exist alongside the physical ones at each level of organization.

Of course, as I noted in the post, we could simply say that those experiential properties are useful fictions, or perhaps pragmatic conceptions, capabilities instantiated by the lower level physics, and that our mental capabilities are constructed from them. But then there’s no real distinction between that view and physicalism, just a more poetic way of talking.

Yeah, Chomsky has definitely given me the impression in the past that he’s an idealist, but I suppose it could have come from a position of neutral monism. In general, I’m not impressed when it’s this hard to understand someone’s position.

LikeLike

“key thesis of panprotopsychism is that the reduction isn’t to standard physics, but only in terms of more primitive experiential properties.”

No. Protophenomenal properties are not experienced but constitutes experienced (phenomenal) properties.

LikeLiked by 2 people

See, the fact that you have to insert a tautological “panprotopsychism’s reduction *isn’t* to standard physics”, in order to avoid reconciling the views, is itself an interesting point.

LikeLike

It is, but I think it’s the point that separates the two views. Remove it, and I think we have just different ways of talking about reductive physicalism.

LikeLike

I think I communicated Chomsky’s earlier statement poorly. With proper emphasis: the mind-matter problem is a pseudoproblem because “matter”, as traditionally conceived, doesn’t exist. The tradition in question goes back to Descartes if not further, and makes some very specific assumptions about matter.

LikeLike

One plausible interpretation of neutral monism is that the distinction between matter and mental substance is artificial and ill conceived. I think it’s a better interpretation than the one that talks about a third kind of substance, but I might be putting words in the mouths of the Russellian’s. (In any case, they seem to be making their own assumptions. Devil, details, etc.) And I’m sure plenty of assumptions about matter from the 1600s are now false. It might be someone from Descartes’ time wouldn’t recognize the current scientific version of the concept.

LikeLike

Right, but think about ordinary citizens today and their views of matter, versus modern scientists. I suspect that today’s philosophers are on average closer to the average citizen.

LikeLike

It depends on the philosopher, but in many cases you’re probably not wrong.

I would note that Russell himself was pretty familiar with quantum mechanics, writing about its implications as early as the 1920s. Although his neutral monism predated it.

LikeLike

I think I’m gonna become an Ismismist. Essentially, my coffeeism, in tandem with my danishism and baconism, consumed over the life of my lifeism, results in a failed coronaryism, followed quickly by a transition to post-existenceism.

LikeLiked by 3 people

So I hear you saying you want more -isms to go with your coffeeisms, etc. Roger, will do. 😉

LikeLiked by 1 person

Sock it to me.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I never was much concerned about Chomsky’s opinions because I took him as a linguist and not having much to say about consciousness or metaphysics. But then, I never read any of his stuff. I have to say that after this podcast my respect for him has gone up several notches, if only because what he says is compatible with my priors.

I’m still trying to figure out what I officially “am”. Currently I think I’m all of these: materialist, physicalist, functionalist, dualist, panprotopsychist, epistemic structural realist, informational realist (see here: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3839564). To the extent any of these are contradictory, my explanation is likely to come down to my definitions of “real” and “exist”. I generally say abstractions(like patterns) are real, stuff exists. Based on your discussion I might rephrase this as relations are real, quiddities exist. (Aren’t quiddities Kant’s neumena?) I would have assumed being a dualist is incompatible with being a monist, but given my terms I have to double check that. (Have to look at the SEP you linked).

I think I like Chomsky’s saying the hard problem is really just a hard question, i.e., a meaningless question. I agree that the question “what is it like?” does not have an answer for an individual experience, but I think it has an explanation. The word “like” requires a comparison, so applying it to a single entity doesn’t make sense.

*

[oh, and consciousness is definitely real as a relation, as opposed to any involvement with quiddities]

LikeLiked by 2 people

Okay, I didn’t get past this early paragraph:

“ Russellian monism can be seen as combining three core theses: structuralism about physics, which states that physics describes the world only in terms of its spatiotemporal structure and dynamics; realism about quiddities, which states that there are quiddities, that is, properties that underlie the structure and dynamics physics describes; and quidditism about consciousness, which states that quiddities are relevant to consciousness.”

Given this description (which is worded slightly differently in the OP) , I think I count as a Russellian monist. The key phrase is the last: “ quiddities are relevant to consciousness.” I say that quiddities are *relevant* in that they generate the relations that we call consciousness.

*

[let me know if I should go read more]

LikeLiked by 2 people

I can’t say I was super interested in Chomsky’s views myself. I just found his assertion that the views could be reconciled interesting. Since I view reductive materialism, functionalism, and illusionism as all reconcilable, the idea of more in is appealing.

But I can’t say Russellian monism is working for me. As I noted in the post, I’m struggling to see quiddities as a productive concept. If I simply deny or ignore them, what are the costs?

Information realism, just based on that abstract, seems very plausible to me. But since I view information as 100% physical, it’s really my default position. Although the idea of reconciling ESR and OSR is interesting. I might have to dig deeper.

You listing all those views reminds me of Pi in Life of Pi, the guy who wanted to be an adherent of several religions, despite their conflicting claims. In the end, the whole story ends up being a romantic interpretation of a much starker version we only learn about at the end. I’m not opposed to poetic narratives, but only if they’re not misleading.

I think before I’d call myself a Russellian monist, I’d finish the first section and peruse the ones on objections and issues. If you do find it reconcilable with physicalism and functionalism, I’d be very interested in seeing your reasoning laid out.

LikeLike

Hmm. I read the whole thing and it did not change anything for me. I think metaphysically I’m a dualistic Russellian monist(RM), being a realist about quiddities and a structuralist about physics. I think consciousness derives from the structures/relations of physics, so if RM requires quiddities to have properties beyond those needed for known physics, then maybe I’m not an RM. But my impression was that Russell was good w/ quiddities and structure, and newcomers are trying to squeeze consciousness into the former.

I’ll try to explain my physicalism and functionalism and dualism.

Physicalism says everything we know about stuff (quiddities) is structures and their relations. We identify things (quiddities) by the patterns of their interactions. Because these patterns are reliably repeatable, we call them structures and assign names to sets of them, like “electron”. I think this is epistemic structural realism, yes?

There are two separate concepts of “function”. The mathematical concept says if a given set of inputs always produce the same output, that’s a function. Quiddities are functional in this sense. Their structures describe their “functionality”. They are thus, also, multi-realizable.

The other concept of function is as a synonym for “purpose”, as in “the function of the heart is to pump blood”. Purpose derives from things with goals. (Will explain this statement further upon request.) This concept of function becomes relevant when considering consciousness, and so explanation of consciousness will be “functional”. Consciousness involves functions (in the first sense) with a function (in the second sense).

My dualism comes from consideration of “physical properties”. For me, at least, a physical property is one that can be measured. Something is a physical property if it’s value can be determined by interacting with a quiddity. Any other property is a non-physical property. I think all non-physical properties that we care about will be relational properties, i.e, properties which can be determined only by referencing other quiddities (or possible quiddities). The two significant (for consciousness) examples are correlation (information) and purpose. Theoretically, there could be properties of a quiddity in itself, but if we can’t determine it by interaction (measurement), then why should we care?

Okay, so what clubs can I get into?

*

LikeLike

Thanks for your thoughts!

I have to admit I haven’t read much of the source material from Russell on his neutral monism. It tends to be very long winded and my time these days is limited. But unless Pereboom is completely misrepresenting his views, the three theses do largely identify quiddities as something in addition to the structures and relations of mainstream physics, and phenomenal consciousness as composed of those additions. (As has been pointed out in this thread, some see the quiddities themselves as phenomenal, which gets into panpsychism territory.)

Of course if we redefine “quiddities” as some (discoverable) part of those structures and relations, as part of the functionality, then everything is “reconciled”, but it doesn’t seem like we’re being true to the actual neutral monist view anymore.

On clubs, I still think you’re a physicalist and a functionalist, but not holding a view that most dualists or Russellian monists would own up to. Maybe I’m being too stringent, but it seems like you’re working so much to steelman the other views that you’re not really accepting them as conventionally understood.

But it’s always possible I’m confused and just not seeing the equivalences between the different views. It wouldn’t be the first time.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hey Mike,

As usual, it’s a pleasure to read a new post of yours. I see that I also have a lot to catch up on, including your article about Ockham’s razor, which I will try to get to if I have the time.

Back on the topic of this thread: One thing that I would say is that I think you go a bit too far in in your assessment that “The second thesis says that quiddities, intrinsic properties, are real. As an epistemic rather than ontic structural realist, I’m open to the possibility that they could be real. However, if they are real, they seem like things we can never know anything about, since knowing would require interactions, extrinsic relations of some sort.”

I say you go too far because to accept that “we cannot know about intrinsic states” is by definition to accept that there accepts an explanatory/epistemic gap. Basically, it’s to accept the hard physicalist stance that some soft physicalists and panpsychists don’t agree with. Nothing wrong with that of course! Although I would just be careful in undergoing your assessment of Chomsky’s attempted reconciliation between panpsychism and illusionism on the basis of this starting point.

One thing I think most people (including you and me) can agree on is that it certainly seems like there exist epistemic primitives when we contemplate the nature of our phenomenal states. It seems to me the existence of these epistemic primitive states, which we all seem to experience, can have multiple explanations. It can be because these are real ontological primitive intrinsic states (as in panpsychism), or because the ontological physical basis (which is itself structural) for these epistemic primitive states is constructed in such a way that the mind only has knowledge of them at some level of abstraction (kind of similar to your software bit analogy). Notice that either possibility is compatible with our experience. The only reason to think that we can’t have knowledge of intrinsic phenomenal states is if you dismiss the possibility of the former case. But this, I think, is incompatible with your assertion that you are “open to the possibility that they could be real.”

In other words, I think you’re putting the cart before the horse. You’re saying that you’re trying not to assume illusionism, but then your argument against panpsychism (which leads you to the physicalist conclusion) would seem to require the premise that panpsychism is false (because if panpsychism is true, then by definition all knowledge isn’t physical, and we would actually have knowledge of intrinsic states).

As for Chomsky, I’m not going to touch that, in part because I haven’t listened to the podcast (an error I intend to rectify soon), and also because I too find it quite difficult to imagine how any purported reconciliation is supposed to take place.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Hey Alex,

I appreciate your kind words. Good to hear from you!

I have to admit I struggle with the epistemic aspect of structural realism. I can’t defend saying quiddities do not exist. Which is why I fall on the ESR rather an OSR camp. But I also can’t see any justification for saying anything about those quiddities, if they do in fact exist. I can see why so many people just go ontic structural realist. As you note, I am admitting to an epistemic gap here. Nevertheless, it’s where I am at the moment. (James of Seattle above linked to a paper that purports to reconcile ESR and OSR, but I haven’t read it yet.)

When I say we can’t know anything about quiddities, I’m saying that in the sense we know anything else about the world, which is there must eventually be energy that impinges on our sensory systems. And that energy is going to only come about from interactions, which require extrinsic relations and structures.

You point out that we do have access to our conscious experience. But as you note, our access to it stops at a certain level. If there are physical processes that constitute them, we can’t access them. But if there are protophenomenal elements that constitute them, we also can’t access them. So I can’t see that conscious experience, even if it is direct acquaintance with phenomenal properties constituted by quiddities, provides us useful insights into the quiddities themselves.

As I noted in the post, if we’ve ruled out the physical processes explanation, I can see phenomenal properties providing motivation for taking quiddities to be involved. But I’m not sure beyond that what could be said about them, other than they exist under that line of reasoning.

In terms of reconciliation, the only path I see for a physicalist would be to regard those extra properties in a sort of platonic manner, as something that might be useful to consider existing, but doesn’t strictly exist in the normal sense. But I’m not sure either camp would really buy that.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Hey Mike,

Thanks for the considered thoughts. My apologies I missed the reliance on proto-phenomenal elements. I had in mind the phenomenal version of RM, wherein we actually have access to ontological intrinsic states as our own epistemic states. It seems to me that is equally a possibility which cannot be eliminated.

The bottom line for me is that a philosophical theory has to explain some sort of phenomena or behavior in order to be useful. By definition, this means the theory has to be verifiable or falsifiable in some sense. I see RM as potentially useful because I think it explains a type of behavior (that of mental states) which physicalist theories seem to struggle with. We talked before about how I think that physicalist theories can perfectly explain your complete verbal and physical behavior, externally and internally, without trouble, but that nonetheless such behavior is not identical to the behavior of certain mental states. For example, we could characterize mental relations, like the spatial relations of visualized objects in your mind, and we would find that they are unique. A physicalist theory would account only for the spatial relations among neurons and other such physical structures, so why do there appear to also exist other types of spatial relations in mental phenomena (among other things)? RM would appear to solve this by postulating the existence of relata (the intrinsic states) which can participate in the required relations.

Anyways, we don’t need to rehash that argument. One thing I should point out is that I’m actually starting to take reductionism a lot more seriously since our last conversation, as a result of the work done by people associated with the qualia structural project. Not sure if you heard of those folks, but basically very recently (especially in the past 1-2 years) there has been some philosophical movement in the direction of exhaustively characterizing qualia in structural terms. The goal is to show (and not just assert) that qualia can exist as non-intrinsic states, by giving them a complete mathematical formalism. In the end it might be possible to show that such states are actually mathematically equivalent to certain physical relations. I’m still skeptical, but I’m definitely warming up to the possibility. I think such an approach is way more promising than illusionism and RM. I’m not sure if we discussed this before, but I actually think that illusionism as is doesn’t go far enough, and therefore can’t be said to solve the hard problem on its own. I think illusionism can only solve the hard problem by denying the existence of all/most mental relational phenomenon (in addition to intrinsicality), which most illusionists don’t appear to be willing to do.

So that’s where I’m at right now.

Cheers,

Alex

LikeLiked by 1 person

Just to clarify, I meant that I don’t think illusionism can solve the hard problem all the way just by itself, unless we take the radical measure of asserting that all mental phenomena (Structural/non-structural and functional/non-functional) are illusory, which you have convinced me that most illusionists don’t actually support.

I obviously still think it might be useful to explain the hard problem in tandem with something like the mathematical qualia structural approach.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hey Alex,

I hadn’t heard about the qualia structural project. Sounds interesting. But I suspect anything they might come up with will be vulnerable to accusations of not addressing the actual issue, since qualia in the philosophical sense are supposed to be intrinsic and ineffable. The ability to analyze them and work them into a mathematical structure seems to imply that it’s more the functional perception that’s being talked about. But maybe they’ve found a new conceptual angle to this.

Your comment about illusionism being insufficient for the HP reminds me of an interesting Twitter exchange Frankish and Chalmers had the other day. (It was buried in a silly meme thread, so I’m not sure how many people saw it.) Chalmers is concerned that Frankish is drifting away from strong illusion into theoretical eliminativism.

Frankish rejects the distinction, which I think is right. But then I think the distinction between strong and weak illusionism is definitional, so I’m probably more absolute in my rejection of the theoretical / illusion divide than he is.

But more to your point, I think your judgment about your mental content not being explainable via neural processing is part of the issue, one arising due to the limitations of introspection. As you note, in principle we should be able to explain all the behavior, including the behavior of talking about our mental states. It’s the idea that there’s something else there, something irreducible, indescribable, unanalyzable, and undetectable via third person methods, that’s being called into question.

Of course, the reductive physicalist / illusionist eventually has to account for the feeling of that idea. (The reductionist sees it as accounting for phenomenality (reconstructed), the illusionist for the illusion of phenomenality, but the accounting should be the same.) As Chalmers notes, the physicalist has to find a solution to the meta problem to conclusively dissolve the hard one.

LikeLike

Hi Mike,

A lot to say here; I’ll be brief.

“qualia in the philosophical sense are supposed to be intrinsic and ineffable.”

They are supposed to be *epistemically* intrinsic and ineffable by definition, but not ontologically. Indeed, the latter would be begging the question. There is therefore nothing incompatible between the starting points of the dualist/panpsychist and the qualia structuralists, since they both agree that qualia exist. The idea of ontological intrinsic states existing “out there” is meant to be invoked as an explanation for our mental phenomena, but it’s certainly not assumed by definition, and as such very much has to be proved. Usually, such proofs take the forms of invoking zombies or inverts to show that there has to be a real physical gap here, but you can definitely always attack the leap from conceivability to possibility.

I actually just spoke with Chalmers by email on this very issue last week, and he says he’s quite sympathetic to the structural qualia aims and goals. He still has doubts, but such doubts are focused on the practical ability of the project actually being able to succeed, and not that there has to be some definitional incompatibility or anything like that.

“It’s the idea that there’s something else there, something irreducible, indescribable, unanalyzable, and undetectable via third person methods, that’s being called into question”

Again, I think this is somewhat backwards actually. The RM/dualist is not committed (or should not be committed) to the proposition that qualia actually are those things as a starting point. Rather, this is something they must arrive at after having argued for the notion that our phenomenal states actually exist as ontologically intrinsic states.

So, the idea that qualia might actually be unanalyzable and ineffable is never meant to be a “get out of jail free card”, it’s something that first must be demonstrated. Just like you wouldn’t start with the assumption that string theory is right and then use it’s unverifiability as a dodge to deflect criticisms. No, that would be nuts and contrary to the spirit of science. You must first demonstrate that string theory has a good chance of being right (maybe by appealing to mathematical simplicity or something like that), and only then would you have the grounds to characterize ultimate reality as being experimentally unverifiable.

Thus, I think it’s a bit of a red herring to imply that non-physicalists believe that the illusionists and other reductionists have to explain the existence of “something irreducible, indescribable, unanalyzable, and undetectable via third person methods”. Once the arguments in favor of the existence of those states are dismantled by the hypothetical physicalist, then there’s really nothing left to be explained. The issue is just that most people on the other side believe the arguments still remain strong.

“As you note, in principle we should be able to explain all the behavior, including the behavior of talking about our mental states”

It’s not the behavior of our verbal reports which causes issues with reduction, but the behavior of the mental states themselves. Also, as I mentioned, there appears to be a serious structural mismatch between the (functional) relations governing qualitative states and the (functional) relations governing physical brain states. So, I don’t think it’s going to be enough to invoke hypothetical limits of our introspection as an explanation for this mismatch, unless you’re prepared to argue that we’re mistaken about our judgements of the functional mental facts, which like I said, most illusionists are not prepared to do.

LikeLike

Hi Alex,

This epistemic vs ontic distinction is interesting. If I’m understanding you correctly, maybe there are opportunities here for reconciliation after all. My understanding of illusionism (strong or weak) is that the epistemic limitations, the fact that we can’t subjectively reduce perceptual primitives, are what mislead us about the ontology. That mismatch is the illusion. (I’ve often wondered if a better name than “illusionism” wouldn’t be “abstractionism”.)

I guess my next question is, what makes you think the underlying ontology is non-physical? If we’re not taking our impressions at face value, then what leads us to think that physics can’t explain it? I generally don’t see non-physicalists talking the way you do here, but maybe I’ve missed some key material somewhere.

I still struggle to see the issue between the functional mental states and brain states. I wrote a reply here, then realized it was largely a repeat of what we’d batted around already. Maybe I should just ask: what is the difference, as you see it, between what you’re talking about and the way an image or CAD design is stored in a technological system?

LikeLike

Another long post coming Mike, apologies:

Yes, I think the epistemic vs ontological distinction is important and definitely changes our interpretations of this topic. Indeed, one of my own issues in our early conversations on this blog was that I failed to make this exact distinction and consequently interpreted your claims against the intrinsicality of qualia as just being the denial of the existence of qualia/subjective states. It was difficult to find any common ground here since it seemed to me like you were claiming that we don’t have any feelings or mental phenomena at all. I now realize that I was grossly mistaken and that we are much closer in our philosophical outlooks.

About non-physicalists not talking in the same way:

I don’t think that’s necessarily true. If you read Chalmers for example, like his article on the phenomenal concept strategy (https://consc.net/papers/pceg.html), I think it’s pretty clear that he accepts there is an inference needed to transition from the epistemic to the ontic. This is how I understand most non-physicalists. The confusion only comes when they speak of qualia as being ontologically intrinsic, but we should understand such talk as implicitly accepting an inference, and not as asserting a truth by definition or tautology or anything like that.

“If we’re not taking our impressions at face value, then what leads us to think that physics can’t explain it?”

To be clear I’m not saying that, and I view what we take as face value as separate from the epistemic vs ontological issue. It’s possible to believe, for instance, that we should take the dualist hypothesis at face value, yet still hold that there’s an inference that needs to be made there; you would just think that the inference is prima facie obvious. But obviously if there was some strong defeater against that inference, then the dualist should drop their claims about consciousness.

As for what we should take at face value, I generally take the opposite approach and so I think we’re on the same page here. Throughout most of my life I was a physicalist until I began to think deeply about the hard problem and realized that reduction was not necessarily so easy. In my opinion, the right way to approach this is to take physicalism as prima facie true. Any alternatives to physicalism should only be believed as a last resort; it’s just that I think we’ve reached that last resort! As I understand it from reading Chalmers biography, he approaches this in much the same way.

On illusionism:

I’m not as well read on this topic as I would like (although of course I have read Frankish), and I must admit that I’m not sure whether illusionism can be characterized as “that the epistemic limitations, the fact that we can’t subjectively reduce perceptual primitives, are what mislead us about the ontology. That mismatch is the illusion.”

For one, this is a very mild claim, one that doesn’t even require hard physicalism (Type A materialism). The soft physicalists (Type B) also believe that we won’t be able to reduce our phenomenal concepts from the inside (see the article about the phenomenal concept strategy). But the illusionists go further in denying that there exists any form of epistemic or conceivability gap, meaning they don’t even believe that there’s a potential problem of reduction from the inside. I have seen some statements from Frankish which seem to belie the above and which advocate for a milder approach. But I have also seen counters by non-physicalists like Goff and Chalmers who argue that such milder re-interpretations on the behalf of Frankish are inconsistent with Frankish’s core position (as laid out in his principal writings), or at least that they really stretch the meaning of our language.

My tentative thinking is that illusionism isn’t the position that the mismatch is the illusion, but rather that our perception of there being a mismatch is an illusion. In other words, we’re not mistaken about the true character of mental states because of some epistemic limitation preventing us from accessing this true (non-intrinsic) nature. We’re mistaken about what the subjective character of our mental states even is. It’s a subtle, but crucial distinction.

I’m not sure how you feel about this. It seems to me that you do accept that there exists an epistemic gap of this kind, but that you believe that such a gap is easily explainable on account of our physical limitations. I actually agree that such a gap (the physical-structural being subjectively perceived as intrinsic) could, in principle, be easily explainable as well, I just don’t think that such an explanation would solve the hard problem (for the reasons I earlier elaborated on).

“Maybe I should just ask: what is the difference, as you see it, between what you’re talking about and the way an image or CAD design is stored in a technological system?”

Yes, this gets to my last point about how I don’t believe that positing the existence of a potential epistemic limit in regard to intrinsicality is sufficient, even if it’s true. I need to think more carefully about how I should present this point, so we don’t risk repeating ourselves. This post is already long enough, so I’ll write a separate reply to explain my reasoning later. I promise to do so in the coming days.

It’s been nice chatting with you.

LikeLike

Just to expand on the illusionism point: in re-reading Frankish I’m becoming more and more certain that my interpretation of illusionism (which was actually my original interpretation from when we started our first conversations, but which I lost confidence in throughout our extensive talks) is correct. That, in other words, the illusionists are NOT saying that we are confused about the ontological nature of our phenomenal states, but rather that we are confused about the subjective nature of such states. We are confused about what it even feels like from a first person subjective perspective, in other words. Note in Frankish’s writings:

“ Illusionism makes a very strong claim; experiences do not really have qualitative, ‘what-it’s-like’ properties, whether physical or non-physical.” p.3 (https://keithfrankish.github.io/articles/Frankish_Illusionism%20as%20a%20theory%20of%20consciousness_eprint.pdf)

Note the emphasis on ‘physical’ as well as non-physical. The alternative claim, that the illusionists are just asserting that our subjective states seem intrinsic because of some physical hardware limitation in our brain, can’t be right because:

1. It’s basically tantamount to the type b materialist assertion

2. The illusionists specifically deny the existence of an epistemic gap

I think this is pretty radical indeed. If we are mistaken about the fact that it even feels like (from an inner perspective) we are conscious, then it seems like the illusionists really are claiming that we are not conscious in any meaningful sense. I think this is epistemically self-defeating, as I argued for in our past conversations (but I think you then didn’t fully grasp my argument because it wasn’t clear that I was objecting to this type of illusionism). That’s because we have to start with our conscious experiences (epistemically intrinsic qualia) to even justify our beliefs in the outside world and the beliefs that led us to illusionism (so it’s self defeating).

If this is correct then I feel we’ve made substantial progress:

1. We’ve established (it seems) that you accept the existence of qualia as the type B materialists and non-physicalists do (as experiences which present themselves as subjectively intrinsic, ineffable etc…), and accept the existence of an epistemic gap.

2 We’ve agreed that physicalism is the obvious prima facie explanation.

3. We agree that physicalism, if it was true, could easily explain the existence of the epistemic gap with regards to subjective intrinsicality.

4. We disagree on whether 3 can close the entire epistemic gap. My argument is that it is not enough on the grounds that ontological structural qualia still need to be physically reduced, and there remain serious problems with doing so.

Chalmers, by the way, as I have gleaned in my email discussions with him, rejects 3. He thinks there still remain important epistemic gaps with regards to intrinsicness, but I found his arguments here to be unpersuasive. So it seems that you and I are closer in our positions. The only thing that remains is for me to justify 4, which I will endeavor to do in my next post later this week.

Best,

Alex

LikeLike

Hi Alex,

No worries on long posts, although I always warn people that I have a tendency to miss points they want responses to when it gets long. But you numbered some points, which helps.

First, let me say that definitions are the bane of these kinds of conversations. You quoted Keith Frankish and his strong claim about qualitative and what-it’s-like properties. Unfortunately, I don’t think he’s the clearest writer on this. (Daniel Dennett does a much better job, but he can get pretty polemical.)

The thing to remember is that when Frankish uses those phrases, it’s in a certain technical sense used by philosophers like Nagel. The problem is the “what it’s like” phrase is often taken to be something obvious and clear. But if it’s not being used in the Nagel sense, then it’s so vague as to be meaningless, and Nagel’s sense is far from theory neutral. In other words, taking Frankish’s statement to be a dismissal of common sense consciousness is a mistake. (Again, his writing makes it too easy of a mistake.)

On the epistemic point, I probably should have clarified the distinction between the epistemic limitations of the subjective perspective vs the objective one. We have a lot of limitations from our subjective perspective, particularly about that perspective itself. The mistake is taking those limitations from that perspective as absolute limitations instead of blind spots that can be overcome from alternate viewpoints. And that’s what I see the objective perspective being, what we get from taking many different perspectives.

So, I can’t subjectively reduce my perception of redness, no matter how hard I introspect. The wiring just isn’t there. The mistake is taking that to be some absolute constraint which implies that redness is something fundamental, instead of a perceptual conclusion for which we have no subjective access to the underlying computations. But once we establish the neural activity that is the conclusion of a certain color in a certain part of the visual field, that can be studied and objectively reduced. (Remember the software bit / transistor analogy. Software can’t go below a bit, but that doesn’t make a bit fundamental, except for the software.)

So, getting to your points.

1. I’m not a type-B materialist, which I hope the above clarifies. Believe me, I’ve dived into the distinction many times, and everytime the type-A view is the one I come away with.

2. I’m not sure I’d say “obvious” here. We’re all innate dualists. I’m not really onboard with the PCS, but I do think it gets one thing right. That innate dualism probably comes because we have very different models for social interactions vs physical ones, which makes it seem like the minds involved in those social interactions are something categorically different. I personally had to be convinced away from dualism.

3. I’m not sure I’d sign up for “easily” here. But I think the subjective epistemic gap is explained by the limitations of introspection. It seems like the mystery of consciousness arises from a mismatch between what introspection tells us and what science tells us about the brain and body. I won’t belabor the point since we’ve pounded on it a lot before, but for me this is the crucial fork.

4. I’m open to being convinced. But I’ve had the same reaction to Chalmers. He usually just takes the gap as obvious. I’ve seen a similar stance from Nagel, Goff, and others. (At least based on the papers and articles I’ve read from them. I have to admit I haven’t read many non-physicalists at length. I read Chalmers’ Reality+ but it wasn’t focused on consciousness.)

The interesting thing I find about Chalmers is how often I agree with him on things other than consciousness, including things about the mind. For example, we have similar conclusions about artificial intelligence and mind uploading. He’s a dualist, but his dualism is so thin that it has only the slightest effects on his ontology. This is why I’ve often wondered if there wasn’t a possible reconciliation between his view and the reductive physicalist one.

Wow, this ended up being pretty long itself. As always, enjoy our conversations Alex!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Mike,

I should begin by pointing out that the most important thing in this conversation is that we agree on what our own beliefs entail, even if we disagree about the true nature of the major positions (illusionism, type b materialism). I’m going to sidestep illusionism a little for the time being and concentrate on type B instead, but I agree with you that a lot turns on what we think the meaning of ‘phenomenal properties’ are.

1) Can you elaborate on why you think that you’re not a type B materialist? Everything you said about the subjective/objective divide is literally word for word what they believe as I have always understood them, and also what I had in mind when I wrote my premise 3. In fact, I have heard the software/hardware metaphor on many occasions employed by such people. Type B materialism is just the conjunction of the premises that:

A) physicalism is true

and

B) there exists an epistemic/conceivability gap between the subjective and objective nature of our mental states

The way they reconcile A and B is by positing that, as you say, “the subjective epistemic gap is explained by the limitations of introspection.”

As evidence, check out:(https://consc.net/papers/nature.html)

and see what Chalmers says under the Type-B subsection, “According to type-B materialism, there is an epistemic gap between the physical and phenomenal domains, but there is no ontological gap. According to this view, zombies and the like are conceivable, but they are not metaphysically possible”

Chalmers also elaborates in his paper on the PCS that he sees the conceivability and epistemic gap as basically the same thing.

Furthermore, it is well known that the illusionists don’t think that there is any sort of conceivability and/or epistemic gap even in principle, so how do you reconcile that with your interpretations?

I’d like to get more into illusionism but first I just want to see your response to the above.

2) Ironically, we had opposite formative intuitions. In my case for example, I really was a physicalist for as long as I can remember throughout my childhood (and Chalmers I think was the same before he got into consciousness). I think we are in agreement though that physicalism is the simplest explanation for our subjective phenomena, and so it should be our prima facie explanation (intuitions aside) if it can succeed in explaining such phenomena (which of course I don’t think it does, see my point 4).

3) I thought I had read you write in an earlier re-telling of your software/hardware metaphor that a physicalist account of the brain can easily explain why we have subjective limitations, apologies if I put words in your mouth. In any case, I would go so far as to say that it’s all quite straightforward. If our subjective introspective powers have limitations, then by definition a lower-level physical base wouldn’t be introspectively observable, turning a subjectively intrinsic state into an objectively structural one.

I haven’t found Chalmers arguments against structural qualia all that convincing here; they basically rely on a

rehash of the old epistemic/conceivability gap. But of course, if 3 is correct, it predicts the existence of that very same epistemic gap, so this argument seems quite weak to me (I think we are in agreement here).

4) Yes, I promise I haven’t forgotten about my argument in favor of 4. However, about Goff and co. taking the gap as ‘obvious’. Are you sure that they don’t have the conceivability/epistemic gap in mind? Remember that illusionism denies the existence of any conceivability gap even in principle. I don’t think Chalmers thinks the epistemic to ontological transition is “obvious”.

LikeLike

Just to clarify in case this might be helpful, when type B materialists speak of the impossibility of closing the epistemic gap, they don’t meant that we won’t be able to conceive of a solution to reductionism by thinking of the matter in some other way (reaching outside our blind spot in other words). Of course that can’t be true because otherwise they wouldn’t be physicalists in the first place!

No, they just mean that there are deep subjective limitations that will always remain because of the way the hardware of our brain is constructed (exactly what you are saying, it seems to me). All we can do is circumvent such limitations through reason, but we can’t actually eliminate them.

The illusionists by contrast seem to really believe that there is no epistemic blind spot to begin with. I agree that your alternative interpretation is plausible, but I think mine is better because it can easily reconcile why:

A) Illusionists don’t believe there exists a conceivability gap in principle (how do you reconcile this?)

B) Illusionism is seen as much more radical than type b materialism (which is basically analogous to what you are saying).

C) Makes the most sense of Frankish’s quote. If Frankish had in mind a heavily theory laden version of phenomenal properties (as something ontologically intrinsic, ineffable) when he wrote that paper, then why would he bother to specify that he doesn’t believe that even physical things can have phenomenal properties? This would be an oxymoron and wouldn’t really need to be specified.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Alex,

So, I think your understanding of the division between type-A and type-B materialists may be off a bit. Consider how little conceptual space you’re leaving for the type-As. If thinking we can introspectively access our own neural processing is required to be a type-A materialist, then no one is a type-A materialist. (Well, at least no one who isn’t deranged.) Hopefully it’s clear people like Dennett, the Churchlands, Frankish, and others like me have something else in mind.

My reading of Chalmers’ categories is that a type-B materialist thinks there is an unbridgeable epistemic gap (albeit not an ontological one as the dualists think). I do think it can be bridged, and noted how above. The key difference is that just because it can’t be bridged from one end (subjective) doesn’t mean it can’t be bridged from the other (objective). A type-B doesn’t think it can be bridged from either end. Not my view. (In general, I’m skeptical of most unknowability arguments.)

It’s worth noting that I also think the only thing to explain is functionality, and that philosophical zombies are incoherent unless we assume the dualism it’s supposed to demonstrate. So I’m pretty solidly in the type-A camp.

LikeLike

Hey Mike,

This is interesting, seems like we believe (almost) the same thing in reality, but we just started with different interpretations of what the other camps were saying and somehow ended up on opposite sides.

“Consider how little conceptual space you’re leaving for the type-As. If thinking we can introspectively access our own neural processing is required to be a type-A materialist, then no one is a type-A materialist. (Well, at least no one who isn’t deranged.”

I don’t think the Type-A stance is that we have direct introspective access to our neural processing, I don’t see how that’s entailed by the denial of an epistemic gap. I think they’re just denying (or at least the strong illusionists are) that we really conceive of phenomenal properties as something intrinsic, ineffable etc… But it doesn’t follow that we therefore conceive them in the correct physicalist way. In other words, I think the illusionists are saying that we’re mistaken about what we introspect, and not just that we’re mistaken about the ontological implications of our introspections (although the former implies the latter). As for the charge of derangement, well consider that this is the exact charge so many have levelled against them! 🙂

However, if I may say something in defense of the hypothetical illusionist I speak of, I actually wish to take back my allegation of illusionism being self-defeating. Just because you think that we’re mistaken about the existence of subjective intrinsic states (states which present themselves as intrinsic to the first person), doesn’t mean that you don’t accept the existence of subjective functional states (states which present themselves as functional to the first person). So, it’s not necessarily self-defeating (I think you can construct a coherent epistemology from the latter). But it’s bizarre for sure!

“My reading of Chalmers’ categories is that a type-B materialist thinks there is an unbridgeable epistemic gap”

Let me level the “this is unfair/unrealistic to my side” charge right back at you. If this was true, then no type B materialist could be a physicalist. Think about it, if there was an unbridgeable epistemic gap that we can’t circumvent in any way, then it would be impossible to arrive at the conclusion that physicalism is true. It’s not mysterianism. So, of course we can bridge the gap; it’s just that we can’t do so from the subjective side. I actually made this exact same point in my last comment.

“It’s worth noting that I also think the only thing to explain is functionality, and that philosophical zombies are incoherent unless we assume the dualism it’s supposed to demonstrate”

Type B materialists also agree that we only have to explain physicality (or functionality); there’s nothing ontologically extra in need of explanation (expect for why we talk about such things). Also, zombies are definitely incoherent if you start with physicalist principles and deny dualist ones, no one is in disagreement there. But that is a question of possibility, not conceivability.

The real question is, are they conceivable? That is, does our intuitive understanding of our mental states predispose us to dualist/zombie intuitions? You already declared that your prima facie intuitions were dualist, so your answer would appear to be yes.

Note that this is totally separate from the issue of whether zombies are really ontologically coherent and possible. It could be that zombies are not actually coherent (as revealed through physicalist reasoning) but that they are conceivably coherent (they are not something unimaginable like a square-circle). I think the illusionists are really saying that they are literally unimaginable, and the explanation for why we think we can imagine them is simply that we are in introspective error (due to an illusion).

To put it simply, Type B materialists agree zombies are conceivable but not possible (refer to the quote in my last post), whereas illusionists don’t even think they are conceivable (refer to the Type-A section:https://consc.net/papers/nature.html).

As always, this has been a very stimulating discussion.

LikeLike

In other words just because you think there is an unbridgeable epistemic gap between our subjective introspections and their real ontological nature (because of hardware limitations), doesn’t mean that you think this epistemic gap is total (as you seem to be charging). It is only a partial gap that is apparent between the subjective and objective, but that doesn’t mean that we can’t arrive at objective knowledge through outside reasoning (if that were true, the type B people wouldn’t be materialist). Nevertheless this partial gap cannot be closed; it’s an inherent biologist limitation to our introspection. All we can do is circumvent it.

LikeLike

Hi Alex,

As I noted above, the definitions here are a tangled knot.

Just to level things a bit, I’m going to quote Chalmers in the paper you cited.

I think my description of type-B which includes an “unbridgeable epistemic gap” matches his “unclosable epistemic gap”. Note the distinction he makes with type-C.

I don’t think the limitations of introspection, by itself, qualify as an epistemic gap, at least not in the sense Chalmers is talking about, since to a type-A materialist, the gap can be closed by bringing in alternate perspectives, which collectively add up to the objective view. (Chalmers’ language toward type-As tends to be a bit strawmannish, but it covers the basic idea.) Which is why I see my view in the description of type-A materialists he gives after the quote above.

Maybe it’ll help if I lay out how I see these positions.

type-A materialist (introspection has limitations, no unclosable epistemic gap, no ontological gap)

type-B materialist (introspection has limitations, an unclosable epistemic gap, no ontological gap)

Dualist (an ontological gap)

Where would you say this goes wrong?

LikeLike

Hi Mike,

It seems like everything hinges on what we think the epistemic gap is. I think the phrase “unclosable epistemic gap” just refers to a fundamental limitation on our introspective ability (call this a partial epistemic gap), whereas it seems you think it refers to the total inability to reconcile phenomenal and physical truths. So, I actually agree with your phrasing of the different stances; I simply disagree with your interpretation.

As for type C, I interpret that stance as being the position that the introspective limits can be overcome if we simply introspect harder (with better introspective conceptual tools perhaps).

Three things I will say in support of my view:

1. To again reiterate, if type B materialists believed in a total epistemic gap (over and above introspection) then they wouldn’t be reductionist physicalists. Remember, the reductive physicalists think phenomenal truths can be purely explained and understood using physical means. But they are reductive physicalists (Chalmers characterizes them as such).

2. Type B materialism is just the stance that we can’t reconcile phenomenal and physical truths a priori, but we can do so a posteriori:(https://philpapers.org/rec/YETDTP-2).

This seems equivalent to a limitation on introspection. Your position that type-B materialism entails the existence of a complete (as opposed to partial) un-bridgeable gap seems unreconcilable with their belief that such truths can be known (and the total epistemic gap closed) a posteriori.

3. Note again the emphasis on conceivability. Conceivability seems to be used by Chalmers as roughly analogous to introspection (he equates conceivability to a priori knowledge in the PCS paper), and yet he characterizes type-A as denying a conceivability gap (analogous to my interpretation that they reject any introspective limit), and Type-B as accepting a conceivability gap.

LikeLike

Hi Alex,

The problem with assuming it’s all about introspection is that it puts illusionists, who take the issues with introspection as a key issue, in type-B territory, something both they and Chalmers agree is not the case.

This is clouded by the fact that the idea of the epistemic gap does arise due to limitations in introspection. But type-As see it as a limitations that can be compensated for. Type-Bs don’t. They think we have to accept brute identity relations instead, albeit ones fully within physicalism.

On “reduction”, again definitions. Chalmers admits in that paper that he’s using “reduction” in a broader than typical manner. In his earlier paper that discusses the type-A vs type-B distinction, he refers to type-A as “hard-line reductionism”, recognizing that there is a difference. https://consc.net/papers/moving.html

This actually fits with the fact that type-B materialism is often referred to as non-reductive physicalism. You can say it’s reductive, but if so it’s a different type of reduction than type-A’s.

The a priori vs a posteriori distinction does get at the difference. “A priori” here is in the sense of a logical account of the reduction being possible, as opposed to the brute-identity relations usually taken by identity theories. Functionalist theories require a priori reduction, but identity theories accept the a posteriori version.

I’m very much not a fan of Chalmers’ use of the word “conceivability”. It either means imaginable, which is silly since I can imagine pink dancing elephants and my ability to do so has no implications for reality, or it means something like logical coherence. He seems to use the ambiguity to rhetorically imply that type-A materialists are unreasonable. In my view, far from his finest writing. (Not that some of the type-As, like Dennett and Churchland, aren’t often just as bad.)

LikeLike

Hey again Mike,

“The problem with assuming it’s all about introspection is that it puts illusionists, who take the issues with introspection as a key issue, in type-B territory”

This is only true if you first assume that your interpretation is correct. But if my interpretation is the correct one, then type A claims about introspection are actually claims about our being wrong about what we are subjectively introspecting/feeling from the first person (as opposed to our just being wrong about the ontological implications of our subjective introspections). Rendering them clearly and conceptually distinct from the Type B stance.

It also seems to accord very well with the illusionists’ language (notice how Frankish often talks about how we misrepresent our own subjective properties to ourselves)

On brute identity:

I’m not sure what you mean by this? Do you mean that you think the type B materialists accept contingent identity relations in our physical universe, but not logically necessary ones? If so, I agree that’s not a form of reductionism, but that’s not my understanding of what Chalmers is saying at all. Furthermore, in reading type B materialists like Papineau, I thought they were pretty clear that they believed in logical/analytic identities. Chalmers also explicitly says that type B materialists believe in phenomenal-physical identity within all possible universes (refer to my quote below).

“A priori” here is in the sense of a logical account of the reduction being possible, as opposed to the brute-identity relations”

If my understanding of your concept of brute identity is correct, then no this seems incorrect to me. The a priori-a posteriori distinction is about the epistemic; it’s completely separate from reducibility. A posteriori truths can be analytic (necessarily true in all possible worlds), as Kripke showed. To quote the PCS paper by Chalmers, “More generally, type-B materialists typically hold that the material conditional ‘P⊃Q’ is an instance of Kripke’s necessary a posteriori: like ‘water is H2O’, the conditional is not knowable a priori, but it is true in all possible worlds” (https://consc.net/papers/pceg.html).

The analogy to water and H20 is very telling. The only reason we might think that water is not H20 is if we didn’t have the introspective knowledge of its detailed molecular workings (and hence that it seemed conceivable to us that the analytic relation might be false). But clearly, we are able to acquire facts and reason our way to that conclusion (and circumvent this limitation). This is exactly what the Type B materialists are proposing.

Again, if this wasn’t possible, then why on earth would they even be physicalist? Belief in physicalism would be purely a matter of faith, which is even crazier a stance then illusionism (I think it’s telling by the way, that no one charges Type B with being crazy, but a lot of people have labelled illusionism so).

LikeLike

Note also that your criticisms of conceivability are misplaced if my view is correct. I think it literally just means “imaginable” and I think when Chalmers and co. (including the illusionists) say that there is no conceivability gap for type A materialism, they are literally saying that it is unimaginable. Of course we all believe that we can imagine it, but this is the illusion. We are just radically mistaken about what we think is going on inside our subjective mental heads.

LikeLike

Apologies. I mistakenly wrote, “contingent identity relations” for my description of brute identities, when I meant to write “nomological identity relations”. The latter being true in our universe but not necessarily true in other logically possible ones.

LikeLike

So sorry for the many posts, I promise this is the last. I thought it important to clarify how I see the difference in introspective limitations between the two camps. The type B people are saying we can’t imagine how the epistemic gap can be breached using only our first person subjective concepts.

The type A people are denying the above, and instead asserting an introspective limitation regarding our ability to imagine things like inverts and zombies (even though we think we can). The type B introspective limitation is supported by the phenomenal evidence we are presented with, whereas the type A limitation is not (they are saying we don’t even have such phenomenal evidence).

LikeLike

Hi Alex,

Well, I think it’s clear we have different definitions for many of these terms. I’m not sure how productive it would be to keep iterating on them.

I will note that Chalmers thinks type-B materialism fails for exactly the reasons you think my understanding of it is questionable, because it’s a slippery slope into dualism. I actually think he’s right on that point. From his Moving Forward paper:

As always, enjoy our discussions!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Likewise, Mike! I too wish to express similar sentiments with regards to our conversations. I agree that it is not helpful to continue re-iterating our different definitions, I simply noted my interpretation of them to avoid the charge of inconsistency (or your criticism that they make type A materialism identical to Type B).

I think I am getting a handle on what you mean by brute identities. Meaning identities which are physically identical to some functional states, but not logically identical (otherwise we would be able to analyze and epistemically reduce them).

If so, I think you are misinterpreting Chalmers words here. I don’t think he’s saying that type B materialists actually believe in such brute identities. Rather, he is saying that type B entails brute identities, as a criticism of the position.

But importantly, no type B materialist believes in actual brute identities themselves. To accept a brute identity is to dissolve the reductionist stance into a dualist stance (everyone agrees on this, so it would be odd if type B accepted this). If you go over my previous quote (in the PCS paper) concerning a posteriori knowledge (it might also be helpful to again go over some Kripke here), you’ll see that a posteriori necessary truths exist, and they are logical and analytical (true in all possible worlds) and not brute. Note again the comparison to the identity between water and H20 which is a logical and analytical truth that is knowable a posteriori and which is very much not brute.

Finally, to quote Chalmers again from that very paper you linked: “it might be objected that if one possessed an a posteriori concept of consciousness – on which consciousness was identified with some neural process, for example – then the facts about consciousness could be derived straightforwardly. But this would be cheating: one would be building in the identity to derive the identity.”

Note Chalmers objection, it’s not that the type B materialists actually believe that you can’t logically derive consciousness from physical processes (he admits they think they can), it’s just that he thinks its circular. Obviously, type B folks like Papineau reject this charge of circularity, and hence reject the allegation of the identities being brute and non-analytical.

Here are some quotes from Papineau to demonstrate my point: “If conscious properties are identical to material properties, then I say there is no mystery of why material properties “give rise” to conscious properties. This is because identities need no explaining. If the “two” properties are one, then the material property doesn’t “give rise”

to the conscious property — it is the conscious property. And if it is, then there is no mystery of why it is what it is.

An analogy will help to make the point clear. Suppose you don’t know that Tony Curtis and Bernie Schwartz are the same person. Then you are told that they are identical. Now, thismight well prompt you to ask for an explanation of what shows they are identical (and the answer, presumably, would be that they always appear at the same place in the causal scheme of things). But it would make no sense for you then to ask for a further explanation of why they are identical… If

they are one, then they are. That single person couldn’t possibly have been two people.”

(http://www.davidpapineau.co.uk/uploads/1/8/5/5/18551740/mind_the_gap.pdf)

Best,

Alex

LikeLike

Here are some additional quotes from Papineau which express basically the same sentiment you have been saying (note the reference to a mind-brain illusion taking place). Don’t you find it strange that people like Frankish are well read on Type B materialists like Papineau, and yet Frankish insists he is making a much stronger claim?

“Here is my explanation of why people are so disinclined to accept mind-brain identity. It relates to the analysis of phenomenal concepts given at the end of the last section. Phenomenal concepts may be similar to proper names in not invoking descriptions, but they are also dissimilar in that they refer by simulating their referents. This peculiar feature of phenomenal concepts gives rise to a powerful illusion of mind-brain

distinctness. Elsewhere I have called this illusion “the antipathetic fallacy (Papineau, 1993a, 1993b, 1995.) I believe that this fallacy is the real reason why so many people think the mind-brain relation mysterious.”

“This subjective commonality between the imaginative deployment of phenomenal concepts and the experiences they refer to can easily confuse us when we contemplate identities like pains = C-fibres firing. We focus on the left-hand side, deploy our phenomenal concept of pain (that feeling), and feel a teeny bit twingy. Then we focus on the right-hand side, deploy

our concept of C-fibres firing, and feel nothing (or at least nothing in the pain dimension — we may visually imagine nerve cells and so on). And so we conclude that the right hand side

leaves out the feeling of pain itself, the unpleasant what-its-likeness, and refers only to the distinct physical correlates of pain.

I think that this line of thought is extremely common, both within philosophy and without. When we use our phenomenal concepts imaginatively, we bring to mind, in a literal sense, an instance of the experiential property we are thinking about. When we use non-phenomenal concepts, this does not occur. And this makes it seem to us that non-phenomenal concepts cannot possibly denote the same experiential properties that are picked out by our phenomenal concepts. (Thus consider McGinn, with my italics: “How can

technicolour phenomenology arise from soggy grey matter?”) However, this line of thought involves a simple fallacy, indeed a species of the use-mention fallacy. There is indeed a sense in which non-phenomenal concepts (like C-fibres firing) do “leave out” the conscious experiences themselves. They do not use such experiences. But it does not follow that they do not mention such experiences. After all, most referring terms succeed in denoting their referents without using those referents in the process. “

LikeLiked by 1 person

I haven’t done that mind chat episode or read the SEP article on neutral monism. Maybe later. I’m currently interested in the provided dualism versus monism chart however. I have a different way of framing this matter. I wonder how much of this you agree with Mike? Or if anyone else has any thoughts, please let me know.

I realize that when people speak of “matter” in this regard that they generally mean this to also encompass energy given the famous equation of E = MC^2. But I think even with such an inclusion the term can be trouble given limited connotations for the word in general. It seems to me that when we replace “matter” with “monistic causality”, or just “causality” for short, we’re also able to razor off various extraneous notions. One such efficiency would seem to be the elimination of neutral monism.

For the dualism category this change doesn’t seem too significant. Here there’s an existing causal world as well as an otherwise non-connected world that nevertheless ultimately facilitates subjective existence in this world, or the mind through which existence is perceived. Theists often refer to this mental part as an eternal soul, and even if worldly brains seem instrumental to such function as well. Of course there are all sorts of non-theistic dualists out there as well.