Among my earliest memories are the TV series Star Trek and Lost in Space, two shows that promised a universe teeming with alien life, intelligent life. As a boy, the aliens seemed everywhere. We’d probably find some on Mars and Venus, and there wasn’t much doubt we’d find them in other solar systems. And that was assuming they weren’t already visiting us and picking up people on lonely country roads or pilots in the Bermuda Triangle.

I gradually became disillusioned about all these possibilities. UFOs (now UAPs) gradually turned out to be mundane phenomena, or military aircraft of some type. Mars was pretty much verified dead, or at least mostly dead, by the time I was ten. And Venus turned out to be hell. For a while the idea of interstellar aliens held out as a possibility, until I learned about Fermi and his paradox.

Physicist Enrico Fermi, at a lunch in 1950, after a discussion about how life should be prevalent in the universe, asked, “Where is everybody?” (Or something similar, accounts vary.) If intelligent life is everywhere, then Earth should have been visited and colonized long ago, certainly long before humans evolved. Yet we have no evidence anything like this has ever happened.

The Fermi Paradox has long struck me as a serious problem for the idea of pervasive alien civilizations. It also seems to fit with a couple of observations about our own planet. Of the billions of species that have ever existed, only one ever evolved enough intelligence to build a civilization, at least that we know of. From this, it seems reasonable to assume that, alien life may or may not be common, but alien civilizations may be profoundly rare. So rare that our nearest neighbors are too distant to have reached us yet.

But there are those who push back against this conclusion. One of them is astronomer Adam Frank, as he did in a recent interview with Lex Fridman. Frank argues that if aliens visited us in the deep past, say hundreds of millions of years ago, we wouldn’t be able to find evidence of it. The fossil evidence is sparse, and Earth’s surface, due to ongoing volcanic and tectonic processes, is constantly being replaced.

Along similar lines, Frank is one of the authors who put forth the Silurian Hypothesis, the idea that if there had been an intelligent species in Earth’s remote past, say 100 million years ago, who managed to create an industrial civilization, we’d have a hard time finding evidence for it.

Although given the effects humanity is having today, I’m not sure how much I buy this. It seems like a civilization with widespread metallurgy, plastics, fossil fuel depletion, nuclear power, and other activities would leave marks in the geological record. And when exploring the details, Frank admits this, along with noting that we could also find evidence on the moon or Mars, both of which have been scanned from orbit pretty thoroughly at this point.

But it is definitely true that if an alien civilization visited Earth in the remote past without settling the entire planet, then we wouldn’t be able to find evidence for it. We can only say they’re not here now, or at least not in any manner that we can detect. It also still leaves our nearest neighbors distant, just in time instead of necessarily in space. It’s also a pretty dark hypothesis if you think about it, because it implies that what we’ll find in the galaxy is a graveyard of past civilizations. And that all civilizations fail to survive in the long run, since it would only take one for them to still be here.

Frank also, with other authors in a recent paper, attacks the idea of intelligence being rare. They focus on the “Hard Steps model” put forth by Brandon Carter, the idea that our evolution required a number of highly improbable steps: abiogenesis, photosynthesis, eukaryotic life, sexual reproduction, multicellular life, etc. If so, then our evolution looks like a profoundly improbable event, and we might be alone in the observable universe.

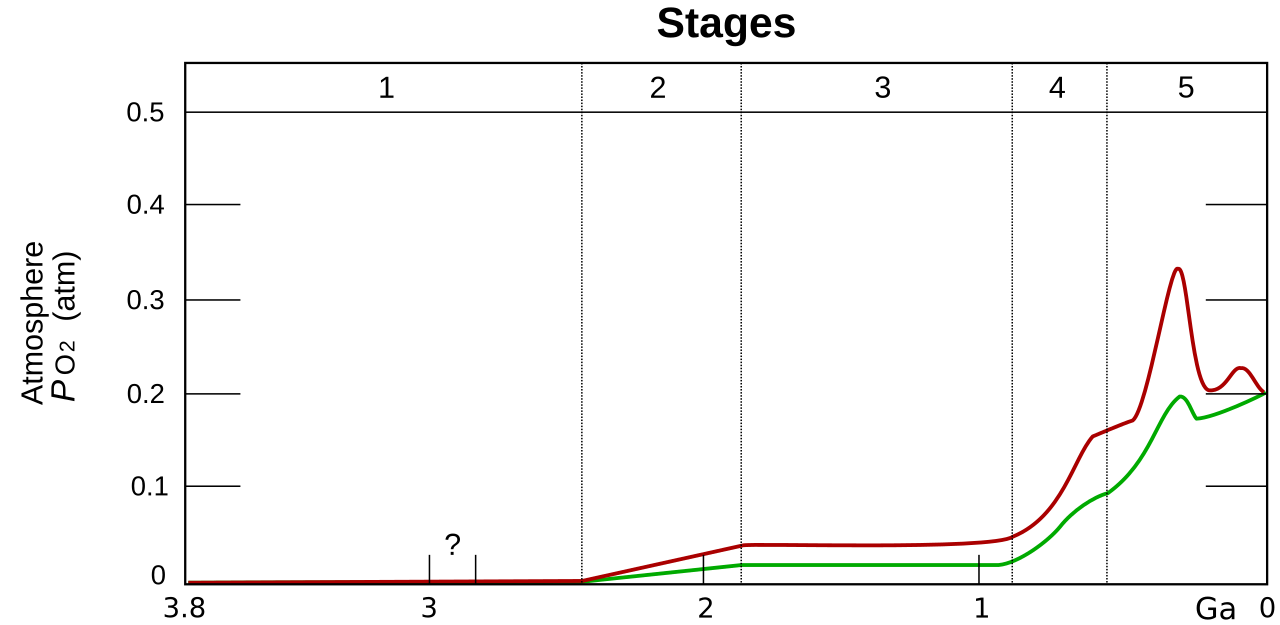

The arguments against this model note that these steps may only look improbable. What looks like singular evolutionary events to us may be because all of the alternate competing versions went extinct. It’s also possible that once a certain ecological niche gets filled, the ability of any other species to evolve into it becomes blocked, since any newcomers won’t have time to become established before losing in competition to the already well established dominant species. That and life sometimes “pulls the ladder up behind it”, such as the oxygenation of the atmosphere from photosynthetic organisms removing the early conditions on Earth that allowed life to begin in the first place.

And the authors point out that many of the evolutionary events required environmental changes before they could take place. For example, animals require significant oxygen levels in the atmosphere to power their bodies.

When we ask why the animals evolved when they did, at least part of the answer was the increasing oxygen levels on the planet. It’s possible that some of these developments might have happened sooner if the conditions had arisen earlier. Although in many cases, oxygen being the key example, it was life itself which created the conditions.

The authors also question how unique humans really are. They argue that there are no categorical differences between us and other species. Capabilities which we once took to be unique to humans, such as tool use and problem solving, have been shown to exist in many other species. Although I think they may overlook the significance of symbolic thought (language, math, etc).

Quibbles aside, I think these arguments do weaken the Hard Steps model, and the idea that humans are unique in the overall universe. But I don’t know that it serves as an answer to Fermi’s original question. If intelligence is everywhere, then where is everybody?

Another possibility not often discussed is that maybe interstellar travel is impossible, or so monstrously difficult that no one bothers. The engineering difficulties are profound. Maybe, despite all the ideas tossed around, none will bear fruit. It seems difficult to imagine we won’t be able to find some way to at least send uncrewed probes, but until we succeed in landing a functioning probe on a planet around another star, we won’t know for sure.

If so, then the only hope of contact might be through communications, but it would likely be conversations held across centuries or millenia. If we become a long lived species, or can find ways to upload and transmit our minds, maybe that would be enough. But it’s still pretty far from the Star Trek type universe.

But maybe I’m missing something. Are there reasons for optimism about alien intelligences that I’m overlooking? Or is the situation as bleak as Brandon Carter saw it, and we’re just fooling ourselves?

The story of “Where are the aliens?” parallels the story of “Where are the gods?” First the gods were in everything: brooks, lakes, trees, mountains, etc. Then they were in deep caves, then on top of high mountains, then in the sky, then above the sky. We looked for them in all of those places and couldn’t find them, so now they are in unsearchable places like “beyond space and time.”

When we conceived of there being sentient species on other planets, we started with they were close by: Venus, Mars, even the Moon. They had to be a threat to make for a good story, and to be a threat they had to be close. But when we looked for them there, we saw “no aliens” so they just had to be elsewhere, enter exoplanets!

What many people do not consider is the vastness of space and the vastness of time. We have been looking for aliens for what, maybe a hundred years if we are generous. One hundred years as a slice of time out of the billions of years of the universe’s time is very, very tiny. The “others” have to overlap us in time for them to detect us or us to detect them. Then there is the amount of space. Radio was invented about 200 years ago so radio waves from here, a sure “tell” of a sentient species being here, have only made it 200 light years away. Our galaxy, one of trillions of galaxies is 100,000 light years across, so the odds space faring aliens would have made it into our little bubble is vanishingly small. Then if you look at the odds of which of the trillions of galaxies they are in, it is even smaller.

Now, if we had been looking for hundreds of thousands of years and had space ships that can do multiples of the speed of light voyages, we might be disappointed in not finding another sentient species in our own galaxy, but in other galaxies, which are millions of light-years away? Even if you detected signs of life in one of those other galaxies, the odds that civilization still exists after the millions of years the info took to get here is almost zero.

I find no realistic hope of hearing from aliens any time . . . ever, not just soon. Although it might be very, very cool . . . if they didn’t decide to eliminate us and take over our planet.

LikeLiked by 3 people

“First the gods were in everything: brooks, lakes, trees, mountains, etc.”

From what I’ve read, the first step wasn’t that the gods were in those things, but that they were those things. Thor starts out as thunder, which appears to strike capriciously, that is with some kind of volition. Maybe if we say nice things about it or give it burnt offering, it will leave us and our loved ones along. But as we learn more about the rules by which those things operate, the volitional aspect moves further and further away, until we’re talking about something outside of the universe.

But I agree, the monsters (and wonders) are always just on the edge of the map, just beyond the horizon. We could even argue that we started with the aliens living in the forests, then on far away islands, then continents. Once those were all explored, the moon and Mars start to be the next frontier.

“I find no realistic hope of hearing from aliens any time . . . ever, not just soon.”

I hold out the possibility that we, or our AI progeny, might someday encounter them. But “someday” should be understood as likely millions or billions of years from now, assuming of course we or our offshoots survive that long.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Whether human-level intelligence is rare in the universe is hard to determine because we lack key pieces of information about life’s origins and evolution. We can’t generalize a lot from Earth Experiment 1.

I have come to think that the engineering problems of interstellar travel may not be able to overcome. If we rule out warp drives, the other options aren’t great. Hibernation for thousands of years. Does the ship itself even survive that long in interstellar space? Simple wear and tear on the ship itself from collisions and radiation might make the survivability of the ship questionable. The more defensive and evasive capabilities it has, the more fuel of some sort it will need. Even if it can suck in ions, it would still require an additional power source to direct the ions. Can nuclear fuel last thousands of years? Any ship reaching our solar system might be so damaged it couldn’t restart its engines to even slow down. The aliens, if they managed to wake up from hibernation, might breeze through, detect intelligent life, gather maybe an entire history of our planet which they beam back to their home planet 20 thousand light years away, then head out into the universe with next stop Andromeda.

Another problem I’ve wondered about, but haven’t found anyone to answer. I wonder how much more mass would Earth need before we would be unable to reach orbit with chemical rockets? Just getting into space might be impossible for some planets without anti-gravity propulsion or some other magic.

LikeLiked by 2 people

I’m on a similar page for crewed exploration, at least of the biological kind. We already see it today. Robots have been all over the solar system. With a few isolated exceptions more than 50 years ago, humans have stuck to low Earth orbit. If we ever do interstellar exploration, it will be begun with robots, and may never move beyond that phase, or if it does, we’re probably as far away from understanding how as Kepler was from understanding how we’d get to the moon when he wrote Somnium.

The energy to keep a craft alive in interstellar space is definitely a non-trivial problem. People talk about the Voyager probes, but they’ve been in very low power mode for decades, and even with that, the plutonium cores that power them are running down. How do we keep equipment functional far from any energy source? There was a concept called the q-drive discussed a few years ago, which held the side promise of maybe being able to get power from the friction of the interstellar medium, but who knows how viable that is.

I don’t know the answer is on more mass, although I’ve heard the same thing mentioned. I do know that the more mass we add, the more the resulting planet ends up being more like a mini-Neptune than an super-Earth.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Have looked at A City on Mars by Kelly and Zach Weinersmith?

It isn’t even a given that humans can endure extended space flight outside the protection of the Earth’s EM field without significant biological or neurological damage. The problem not only is reduced gravity but cosmic radiation. Machinery is subject to the same problem. One of the recent problems on one of the Voyagers was believed to be damage to parts of the system memory from cosmic rays. I guess potentially the problem be fixed with the development of low-mass shields.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’ve owned A City on Mars for a while now, but haven’t read it yet. I need to. I’m familiar with a lot of the issues it discusses, but I know I’ll learn a lot from it.

Machinery does have issues, but they’re much easier to solve than the ones for humans, if by no other way than redundancy. But yeah, when it comes to space exploration, the presence of a human crew exponentially increases the cost and complexity. I don’t doubt there are solutions, but it comes down to how much it’s worth it to us to overcome them.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Same with me and the book.

Even with machinery, we don’t have any idea what it could encounter in interstellar space during 100K+ years. The faster ship travels the greater the force of impact. Even a small object could provide a devastating hit to something traveling at a percentage of light speed. The more shielding the heavier the craft. The more evasive capabilities the more the power requirements, the heavier the craft.

What’s more the ship needs the ability to slow down if it is to do any significant exploration, then be able to maneuver in orbits. There would probably need to be secondary propulsion systems and exploratory craft for the planets. All of that stuff has be dragged along and be able to spring to work after several thousand years in interstellar space .

LikeLiked by 1 person

Slowing down is the big one. Many of the others might in principle be handled with redundancy (like Breakthrough Starshot’s plan to send a fleet of tiny probes). And conceivably even a tiny probe, if it’s a universal constructor, could find raw materials and bootstrap construction of everything else it needs at the destination. But I haven’t seen a good solution yet for the deceleration phase. We can use planet bound lasers to accelerate a tiny probe, but there won’t be such a laser at the destination to slow it down. And anything we add to make it happen leads to the complications you talked about.

And as you note, we can’t just go slow. The longer we take, the less likely any machine is to work correctly. We might imagine one working after a few decades, but when it gets to centuries, millennia, or longer, it becomes increasingly dubious.

It might well turn out to be impossible. But I don’t know that it’s productive for us to assume that, at least unless we’ve tried for millenia without finding a solution.

LikeLiked by 1 person

We should consider the possibility that we just so happen to be the *first* intelligent civilization in the region, or among the first, and others will arrive soon. We might think it’s unlikely that we would be the first, but whoever was first would always be unlikely in that way, and yet someone has to be first to the party.

Another possibility is that, like you mentioned with other stages in evolution, once one intelligent civilization appears it will take away the opportunity from others. Already multiple human species have gone extinct and we’re decimating life on earth. When the first intelligent civilization does get to other planets, our presence might prevent others achieving what we have, so that we create our own cosmic loneliness…

LikeLiked by 2 people

I think it’s very possible we’re the first, at least in our neighborhood. And definitely our presence might prevent the evolution of other intelligences. This isn’t necessarily because we’d explicitly prevent it, but more because we would alter the dynamics. Even just putting intelligent creatures in comfortable habitats might deny them the selection pressures they’d need to evolve stronger intelligence.

But we might be able to alleviate our loneliness with AI and/or uplifting other species. Of course, that means creating or molding systems into our image, at least our mental image. So it wouldn’t be quite the same as encountering something completely alien. Although if we spread into the universe, the various branches of humanity (or humanity’s offspring) might in time become as alien to each other as an entirely separate species.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Exactly. I’m also hopeful that our presence is actually uplifting other species already. Eg dogs are better at cooperating than wolves, at least in certain ways. And there are monkeys that have learned to trade with us. And some evidence that other animals that are around humans more are smarter than their more wild counterparts. It seems plausible to me that we might be in an intelligence arms race, like the sensory/movement arms race that sparked the Cambrian explosion.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Interesting proposition, that we’re already uplifting some species. We’re certainly breeding them (not always intentionally) to be more adaptive toward us. But I was thinking more along the lines of David Brin’s idea of genetically modifying species to be more intelligent. Although I have to wonder how well that would work for any non-primate species. Would an uplifted dog, assuming nothing else changed, really be happy as a dog?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Ah, one of my favorite topics. Do you remember my position on this? A couple of hints:

We are the spark.

”There can be only one.”

As a dyed in the wool Singularitarian (Vingean, not Kurzweilian, so, no mind uploading), I see the universe as a pile of oily rags in a hot garage. Eventually there will be a spark that ignites the pile, but what are the chances that a 2nd spark will happen before the whole pile is aflame?

How long did it take to go from hunter/gathering to farming? How long did it take to go from farming to industrialization? How long did it take to go from industrialization to flight? How long did it take to go from flight to leaving obvious signs on other planets?

Assuming no human extinction event in the near future, how long will it take before we start sending AGI-capable ships, capable of building anything we can build (including more AGI-capable ships) toward every star in our galaxy at speeds approaching (90%?) the speed of light? So how much time between between developing language and getting to the far side of the galaxy? 500,000 years? Seems like dinosaurs could have developed a smarter, technological species. But they never did in the millions of years they were around.

Humans may end up following the AGI ships at some point, but the galaxy will be changed before they get anywhere interesting.

*

[I still look forward to visiting Mars, but not until the robots build some nice hotels.]

LikeLiked by 4 people

I didn’t remember your position, but that fits with the other things you’ve discussed. I agree with much of it as the most plausible model. Although I’ve grown leery that achieving near light speed is as inevitable as science fiction makes it sound. But really we just need to go fast enough so that our self replicating craft continues working long enough to reach its destination. Once we can do that, it seems like just a matter of time.

I think biological humans will always be far slower and more limited spreading into the universe than the engineered minds. If a human wants to explore the universe, in any meaningful sense of “explore”, they will likely have to remake themselves, whether gradually or all at once. Otherwise having to cart around portions of the old biosphere will always leave them hobbled.

I’m not as keen to visit Mars as I used to be. I’m more aware of what the day to day experience of that would be. If they can give me a virtual environment to experience it in, I think I’ll be happy.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Mine too.

LikeLike

How long before we reach “speeds approaching (90%?) the speed of light?”

Maybe never.

LikeLike

• Intelligent life does not mean technically advanced, electromagnetic energy manipulating life. Homo [whatever], many of them intelligent species, have existed for hundreds of thousands of years. Only in the last couple of hundred years have we been capable of interacting with the cosmos. Intelligent life might be everywhere. But the exquisitely unique conditions to allow us to communicate with and travel through space are astronomically rare.

• Von Neumann probes, yeah, we’ll be sending those out in the next thousand years, if we survive. And they’ll not only exhibit information gathering and response, and potentially replicating ability, but will be “seed” probes. If conditions are ripe, they’ll sprinkle about life, earthen life. (With robotic nannies to raise and distribute humans or our AI equals.)

• Earth’s bio-signature has been delivering its “Life Here” signal for a few billion years. That’s exactly what we’re looking for when we search for exoplanets. As we find so few (any?) Earth equivalents the probability that our bio-signals have been detected and acted upon falls to nil. And the lack of evidence (I don’t buy that all evidence would have been erased), supports the “Earth called, nobody answered” premise.

• Any technologically advanced species, for which we have one example, us, requires such a confluence of factors, each of which needing an analog, that the odds dwindle to laughable rates.

— Metal rich, iron rich planetary crust.

— Trees (or their analog; without wood, we’d still be groping around in the dirt.)

— Beasts of burden (imagine humans surviving with only their own hands to procure, transport and distribute food).

— Windows of geologically, minimal catastrophic incidents, climate stable time. No Holocene, no civilization. Just wait for the next Carrington or worse, Miyaki Event (10x). Techno-capable life must build up its capability between these devastating solar events.

— And what would humanity have done without the flood of nearly-free-energy that is fossil fuels? If Greek and Roman societies are any indication — burning all their wood for fuel — they’d have eventually discovered geothermal, wind, photovoltaic, and eventually nuclear energy all for generating electricity. But that might have taken millennia. And might have worked if humans could have survived themselves and all the other catastrophes that would have literally plagued them.

These and more aligned to bring us to this point, this conversation. Intelligence might be rampant in the Universe, but the conditions to support that intelligence to the point where we could detect it?

There is no paradox. Our existence, as we are today, is 2^70 rare.

LikeLiked by 3 people

That’s another question. Even if life existed on a planet, how likely is it that fossil fuel would be created there?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Good point about technology. If humanity had been wiped out by a plague 200 years ago, the only real trace of our existence would have been all the species we wiped out, something indistinguishable from all the other mass extinction events..

I’m not sure about the “seed” part, at least if the idea is that it would be normal biological humans. I suspect we’re going to find that alien biospheres are worse for natural humans than no biosphere at all. Maybe seeds highly engineered and tailored to the destination environment, but that will require we already know a lot about that environment.

Definitely Earth’s biosphere has been detectable from large distances for a long time. The idea that every alien civilization, if they’re there in numbers, would be completely uninterested seems dubious.

Agreed on a confluence of factors. I agree trees for us to evolve a primate type body, but would also throw in grasslands for us to learn to walk upright and free our hands. But I do suspect this might be ameliorated somewhat by alternate paths for that convergence. It’s very hard for us to imagine those alternate paths, but I’m pretty sure if we ever encounter an alien biosphere with its own animal life, we’ll discover just how limited our imaginations have been.

So I wouldn’t say 2^70 rare, which would put our nearest neighbors profoundly far away. But I do think the probability is low enough that they’re likely hundreds of millions or billions of light years away.

LikeLiked by 2 people

The probability of an alien civilization is not all or nothing. It depends from the start on the probability of a cluster of local conditions that make the so-called Hard Steps even possible. These initial conditions might not be highly probable, but neither are they highly improbable; they could occur in pockets here and there. These pockets may be so few and far between that so far we have not encountered any others.

Even so, for anything to come of these conditions, the so-called Hard Steps must occur. If they are truly hard, or even a bit hard, this would reduce the number of candidates. Only if the Hard Steps were as easy as falling off a log could we remotely expect to find civilizations everywhere.

The argument that the Hard Steps may be surprisingly trivial, even when the evidence suggests otherwise, is in polar opposition to a competing story that evolution is improbable and a designer is required. This opposition seems to be a great motivator in coming up with good reasons why life is not so mysterious, despite any appearances to the contrary.

LikeLiked by 2 people

I do think there’s a lot of room between profoundly improbable and inevitable. My take is that some parts, like life itself and photosynthesis, might be inevitable under the right conditions. But as we get to complex life, things become progressively improbable. A species intelligent enough to ponder the universe might be pretty improbable, improbable enough to make our nearest neighbors be very far away.

But who knows? Maybe they’ll show up tomorrow and show I’m all wet.

LikeLike

I’m hoping there are some ‘good’ aliens out there who have escaped the endless and senseless violence endemic in our species. Or is this just another pointless ‘god desire’? Highly probably.

LikeLiked by 2 people

It seems like any aliens would be the result of evolution and so subject to pressures similar to the ones that molded us. Although if they’ve reached the point of being able to modify their own minds, maybe they’ve reconstructed themselves (or their progeny) into their their idea of moral exemplars. Of course, that doesn’t mean their exemplars would be anything like ours (even before considering that we ourselves can’t agree on what is exemplary).

LikeLiked by 2 people

Sorry for length of reply, but went through similar childhood reactions, and this post pretty much sums up my ideas on the topic.

https://skirmisheswithreality.net/2017/12/30/how-not-to-think-about-space-aliens/

LikeLiked by 1 person

Our being the first intelligent species in the galaxy, while possible, violates the Copernican principle. But a race only 100,000 years older than us could have colonised the whole galaxy, if not directly then with robots or some kind of remote exoforming.The theory of Eternal Inflation suggests an answer, which is that many millions of new universes, like our observable universe, are being created every second, each with their own laws of physics. In such a scenario we are far more likely to find ourselves in a young universe than an older one, since young universes will be the great majority. I wanted to mention this because it does resolve the Fermi paradox, but it’s unsatisfying to me as it cannot be proven. I think it is far more likely that intelligent species wipe themselves out, or burn all their resources and go extinct, before they have the opportunity to colonise outer space.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for commenting.

It’s definitely possible that intelligent species wipe themselves out. But as I noted in the post, my difficulty with that answer is you can’t have any exceptions. It can’t be most, or even virtually all species destroy themselves. It has to be all without exception, since it only takes one to still be here.

You’re right that the other universes can’t currently be tested. But it’s worth noting that given current cosmological models, our universe is very young right now. There’s orders of magnitude more time ahead of us than behind. So it’s quite possible we’re just the first on the scene, at least for our region of the universe. Of course, the Vogons could show up tomorrow and prove me wrong.

LikeLike

I’ve come to think about the Fermi Paradox in two distinctly different ways: what’s the real solution and what solutions are good enough for Sci-Fi?

The real solution, I think, is some variation of the Rare Earth Hypothesis. We’re not alone in the universe, but planets like Earth are super rare, and so our nearest neighbors could be so far away that we may as well be alone in the universe.

For Sci-Fi purposes, my favorite explanation is the Zoo Hypothesis. Aliens are out there, and they know about us, but for whatever reason they’re choosing to leave us alone. Maybe there are laws against disturbing primitive planets, like Star Trek’s Prime Directive.

I also like the idea that maybe something happened in our galactic neighborhood recently (i.e., in the last billion years or so). Maybe there was an interstellar war that wiped everybody out, or maybe there was a natural disaster like a magnetar explosion that destroyed all the nearby space-faring civilizations.

I’ve also come around to the idea that maybe we’re the First Ones, or we’re among the First Ones. I read a short story a while back where various alien races are trying to figure out who left these weird ruins on all their planets. Turns out it was us. It was a good story.

But again, those are all ideas I think are good enough for Sci-Fi. In the absence of any other evidence, the Rare Earth Hypothesis seems like the most plausible explanation to me.

LikeLiked by 1 person

The Rare Earth Hypothesis is a possibility. Although I think looking at ourselves with the Copernican principle leaves logical space for microscopic life to be common, complex life to be moderately rare, and civilization producing intelligences to be profoundly rare. Of course, logical spaces is just possibilities.

On sci-fi scenarios, the idea of a war wiping everyone out reminds me of a story I read decades ago. Astronauts are exploring other stars but not finding any planets around any of them. Finally they discover a planet around a star and land there, and encounter an alien who is puzzled to find them “in the desert”, a region of the galaxy with no planets, which resulted from an ancient interstellar war when the rest of the galaxy eradicated an evil alien species. As the alien describes the evil species including cruelties that reminds one of the astronauts of things from human history, it becomes evident that we are that evil species.

The Berserkers / Inhibitors scenario can work pretty well too, the idea that there’s something out there destroying all intelligent life. And with Earth blasting out EM signals, it’s only a matter of time before they find us. Although sometimes the entities only attack space faring civilizations.

But the best I remember is Vernor Vinge’s zones of thought (A Fire Upon the Deep). Earth is in a “slow zone”, where the laws of physics limit speeds and intelligence. But moving further out to the rim of the galaxy enters the faster zones, which allow FTL technologies and other capabilities.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I like the Berserker Hypothesis, too, though I feel like it limits your options for what kind of Sci-Fi story you want to tell. The idea of slow zones and fast zones is cool. Maybe that connects somehow to dark matter altering the rotation rate of galaxies.

The important thing to me is that if you’re going to do Sci-Fi with lots and lots of aliens, you need to offer some sort of answer to the Fermi Paradox.

LikeLiked by 1 person

A recent awareness regarding the origins of chert & flint: If early Earth didn’t possess diatom-radiolarians or sponges (both of which build their skeletons from silicon) the deposition of silicon on the sea floor would not have allowed for the generation of those glass-like minerals, without which early humans would not have been able to find suitable tools for killing, skinning, butchering and general cutting work.

Would Neanderthals & Homo Sapiens been able to survive without flint & chert? One more unique factor in Earth’s and Humanity’s development.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I think it’s fair to say they wouldn’t have evolved without it. But the question is whether there are alternate paths to mastering energy other than the one that was available to us in our biosphere. Maybe not in the vast majority of biospheres. So it’s rare. But how rare? Fermi implies it’s rare enough that they’re not here. But how rare beyond that seems undetermined. For now.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Biological manipulation of electromagnetic energy, telepathy at kilowatt scales? Maybe group telepathy to induce a megawatt signal? Other means to generate a substantial signal that doesn’t require metallurgy?

LikeLiked by 1 person

I was more thinking that a biosphere may produce other volatile compounds that an intelligent species could notice and utilize. What might those be? I don’t know. I’m not enough of a chemist. But I suspect if we ever do encounter another civilization, or the remains of one, or even just other biospheres, we’ll find how constrained our imaginations have been.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Since first hearing of Fermi’s paradox, I have thought it slightly ironic that he, who is best-known outside of physics for his role in developing nuclear weapons, was at a loss to think of reasons why technologically-advanced cultures might not last long enough to spread across the cosmos.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Based on the little I’ve read about him, I suspect he understood he’d contributed to a candidate explanation.

LikeLike

Another factor in this massive, expanding Drake Equation…

Have you heard about the link between the Carboniferous era and the lack of bacteria and fungi to breakdown the lignens & cellulose that accumulated? It’s why the world’s arable lands are not now covered in 500 feet of topsoil–microbes. If they’d developed earlier, no, or at least less coal would have been created.

Another along the same lines…

Post KT impact, mammals arose and surpassed prior reptilian dominance due, presumably to fungi and bacteria thriving in the impact winter gloom. Mammals’ higher body temperature afforded them protection. Cold blooded reptiles suffered.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Definitely our current world is highly contingent on a lot of events that could easily not have happened, or could have happened in a different order with drastically different results. But the question is, are there alternate paths to a civilization, ones that might be radically different from the ones we took?

There probably aren’t enough for civilizations to be pervasive. But there may be enough that our nearest neighbor may only be hundreds of millions of light years away instead of outside of the observable universe. Of course, the difference is largely irrelevant to us, but it might not be for our distant descendants, biological or AI.

LikeLiked by 1 person

What I’ve tried to do is examine the one example we have. Identify all the coin flips that landed heads to get us here. Any speculation outside of our reality is pure conjecture. “This is how unique we are.” Sure, there may be other paths, but this is the only sure one we know of, and look how crazy-unique it is!

LikeLiked by 1 person