On Twitter, the Neuroskeptic shared a new paper, in which an Israeli team claims to have demonstrated phenomenal consciousness without access consciousness: Experiencing without knowing? Empirical evidence for phenomenal consciousness without access.

A quick reminder. In the 1990s Ned Block famously made a distinction between phenomenal consciousness (p-consciousness) and access consciousness (a-consciousness). P-consciousness is conceptualized as raw experience, qualia, the “what it’s like” nature of consciousness. A-consciousness is accessing that information for use in memory, reasoning, verbal report, or control of behavior.

The paper notes that this distinction is controversial. While widely accepted in many corners of consciousness studies, it’s been challenged by others, notably illusionists. The paper cites Daniel Dennett and Michael Cohen in particular as challenging the possibility of gathering data about p-consciousness, since any data gathered has to come through a-consciousness. It cites their 2011 paper, and a couple of others, as providing criteria for establishing p-consciousness.

Such evidence would have to meet three conditions: (a) participants should have no access to the stimulus during its presentation, (b) they should nevertheless demonstrate that they had some qualitative, phenomenal experience of the stimulus, and (c) it should be established that (b) does not simply reflect unconscious processing

Unfortunately the full version of the 2011 Dennett paper isn’t open access, but I question whether Dennett would be onboard with the “during its presentation” stipulation in (a). It doesn’t seem to fit with how he sees consciousness working as described in the multiple drafts discussion of his 1991 book, Consciousness Explained, which uses the phi illusion to deduce that whether content is conscious is always an after the fact determination. And that stipulation in (a) is crucial for the claims made in this paper.

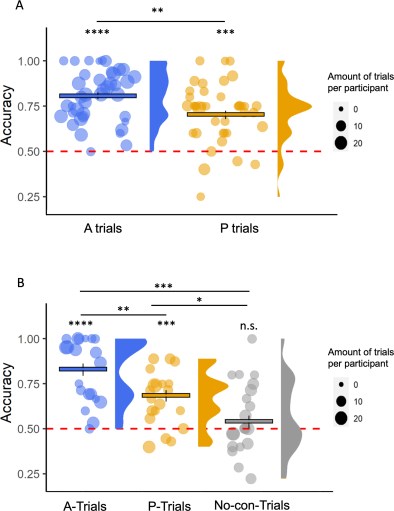

In this study, participants listened to a number of sounds and had to answer questions about them. Sometimes one of a variety of pink noise sounds played in the background. Participants were queried during the pink noise to see if they heard anything. Then the pink noise would end, and participants were asked if they detected the change. Finally, in a second experiment, participants were given a forced choice to identify which of the different pink noises they actually heard.

In most trials (68%) participants attested to being aware of the noise (a-conscious aware, the A-Trial group) and its end, and their forced choice identifications were more accurate than chance. 20% never acknowledged being aware of the noise (the No-con Trial group), neither while it was being played nor its end, and their forced choices accuracy was statistically equivalent to chance guessing. The paper interprets this group’s processing of the pink noise as being unconscious.

However, some (12%) weren’t aware of the noise until it ended, but could then acknowledge that it had been playing (the P-Con Trial group). Similar to the A-Trial group, their forced choice accuracy was better than chance, although not as accurate. This is the group the paper interprets as having p-consciousness of the pink noise without a-consciousness of it. The argument being that they could recall its qualitative distinctiveness.

And here we come to the crucial question. Participants in the P-Trial had to access the memory of their sensory information to report on it, even retrospectively. So, does the sensory processing, prior to them accessing it, count as conscious experience? The paper authors clearly interpret it that way, although they acknowledge at the end of the discussion section that there may be no way to establish completely whether it actually was conscious. It depends on what we require for putting something in that category.

I’m pretty sure someone like Stanislas Dehaene would say that the pink noise perception was merely preconscious, hidden behind inattentional blindness, albeit close to the threshold until change detection caused it break through. And based on the material I’ve read from Dennett, I think he would largely argue there’s no fact of the matter here, only what we retrospectively recognize as having been conscious. Which is why I wondered above if he would agree with the “during its presentation” stipulation.

Which brings me to a version of the perceptual hierarchy of consciousness I’ve discussed before, a series of layers that different people may stipulate as necessary for content to be conscious (other than the last one, which everyone would agree is unconscious). Modified a bit for a-consciousness terms, it goes something like this:

- Conscious content is the output of access processes.

- Conscious content is the current target of access processes.

- Conscious content is any processing that could be the target of access processes.

- All other content beyond the reach of access processing.

If you see 3 as sufficient for consciousness, then you may agree with the paper authors. If 2, then you’re probably closer to cognitive theories like global workspace, multiple drafts, predictive coding, etc. If you think 1 is required, then you’ll likely be more in the metacognitive camp, preferring higher order thought theories, or models like Michael Graziano’s attention schema theory.

The question, I think, for those who do see 3 as sufficient, is it sufficient for a system that doesn’t have access mechanisms, or that only have a primitive version of it? If yes, then does that criteria also apply to machines? If only living systems qualify, then what specifically about those systems makes the difference?

One thing I do think these results highlight though, is that whether something is or isn’t being accessed isn’t a simple binary thing. The dynamics are complex, with many levels, and it shouldn’t surprise us that there are edge cases. This seems like another challenge for global workspace theories that insist that only an ignition type of event heralds access, but seems to sit more comfortably with Dennett’s multiple drafts version.

Unless of course I’m missing something? Are there reasons to think this paper will be more convincing than I’m seeing?

“ other than the last one, which everyone would agree is unconscious”

[hold my beer]

Just checking: if system A is internal to system B, can A be conscious in a way that that consciousness is not available to B, so is “unconscious” w/ respect to B, but conscious w/ respect to A?

I think so, so both 3 and 4 can be conscious internally, and are unconscious at the higher level unless and until they are in fact accessed by the higher level system.

*

LikeLiked by 1 person

[beer held]

On A being conscious to itself while unconscious to B, I think the answer is yes. A case can be made that a group of humans is conscious, but any one person in the group wouldn’t count as that group’s consciousness, although some may play a crucial role.

The question is, how simple can A be before it’s no longer conscious? If we go with your answer (input-output process, psychule?), then there’s no lower boundary. But you have to admit that the consciousness of something like a logic gate is very different from what people have historically used that word to refer to.

LikeLike

Just so ya know, the Psychule concept has been updated slightly. The lower boundary is a two step process: the creation of a sign vehicle and the interpretation of said vehicle (so at least 2 input/outputs). I think that has the basis of everything that people refer to, especially “aboutness”. “What it’s like”-ness would require more than one of these, but that’s like saying wetness requires more than one molecule of water.

But I think the split-brain stuff shows that most would consider the non-verbal hemisphere independently conscious, while largely unconscious to the verbal/dominant system.

*

LikeLiked by 1 person

Good to know on the update. Thanks. That does put more of a floor on the complexity. Although the distinction between sign vehicle and interpretation may be a bit dodgy with organic nervous systems. It seems like interpretation begins in the sense organs, like the retina, with later layers adding additional interpretation as information propagates..

On split-brains, sure, but a hemisphere is a very complex system. It’s basically a full brain for one half of the body. And it’s not clear that the non-verbal hemisphere isn’t part of conscious processing in a healthy subject.

LikeLike

Obviously the non-verbal side processing is part of the healthy “subject” processing, but I’m gonna say that non-verbal processing is sending sign vehicles to both sides (unless the pathway is cut), and the consciousness happens when something responds to (=interprets) the sign vehicle.

*

LikeLike

In your framework, what would be an example of a system or sub-system right on the border that is conscious, vs something on the other side of that border which isn’t?

LikeLike

I guess the classic example would be the digital thermostat v. a standard analog thermostat. The key difference is having an intermediate somewhere in the process whose sole purpose is to carry information. And by information I mean mutual information, aka correlation. The semiotic term for such an intermediate is sign vehicle. BTW, for a diagram see my Twitter banner.

*

LikeLike

Thanks. I wonder if it depends on just how sophisticated the digital thermostat is. I could actually see someone saying that even an analog thermometer has mutual information / correlations.

LikeLike

Mutual information/correlations are the panprotopsychic properties, but they’re not enough for me. The key (for me) is to have an intermediate whose *only* *purpose* is to carry the information. As you say, everyone can have their own idea of consciousness. If you want to be a panpsychist, you could just say any physical interaction is consciousness based on the mutual information generated. But the problem is any given sign vehicle will have some degree of mutual information with essentially any physical system involved in its past, all the way back to the Big Bang. That’s why the response to the vehicle is important, because that response will (probably) only be relevant to a specific other physical system, and the mutual information w/ that system will ideally be higher than all the others (but not necessarily). It’s the response/interpretation that provides the specific aboutness from a group of potential aboutnesses.

*

LikeLike

Interesting point about mutual information. Taken to its extreme, it would seem to leave quantum entanglement as the ultimate basis for consciousness. I’m sure mystics could make something out of that, if they haven’t already.

So, with the need for the interpretation, in the perceptual hierarchy, would you still say consciousness is in 3? I suppose maybe it isn’t for the system in question, but you’d say the various internals for 3 would be separate consciousnesses? Maybe that just brings us back to your initial point.

LikeLike

Sounds like stimuli (phenomena) are being recorded while the subject is unaware of the recording process. And then upon review of the past, it’s determine that there was *something* else going on, that only now registers as a phenomena. And that this “record” is somehow attributed to some level of consciousness.

Like asking a car accident victim, right after the incident, “Do you recall what was on the radio? How cold or hot you were? If you were hungry or had elevated body odor?” — What are you talking about? The victim would say. No doubt all of those things were being recorded, but, persisted into an area that could later be “accessed”?

Preconsciousness sounds about right.

If just before the collision, the victim had said to their partner, “I could go for a pizza,” then the hunger stimuli, which had been there for many minutes, was elevated and focused into actual awareness. Until then, it was just telemetry of a complex system that ingests and discards data continuously.

LikeLiked by 1 person

The word “phenomena” has a particular association with subjective experience in philosophical talk, but I think I catch, and agree with your meaning. My way of thinking about it is stuff gets lodged in short term memory, which fades pretty quickly unless attended to in some manner. But change detection triggers some level of attention. The noise ending is that change. Bringing in the sound from seconds earlier doesn’t strike me as anything surprising.

So in your accident example, most of that would have faded unless something pulled it into attention enough for it to leave a more enduring impression.

And the pizza suggestion is a good example of something else triggering attention on something that might have been just below the threshold. That one doesn’t even really require memory since presumably the hunger sensation would be ongoing.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Cool.

What happens when we have a salvo of competing stimuli where of the half dozen, only one or two can get through? Like the guy in the control room can only work on one or two things at a time.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I think that’s attention, evolution’s solution for choosing which of the stimuli coming in an animal should focus on, since it’s limited in how much it can do at one time. But attention is a multilevel phenomenon. We can be cutting the grass, with low level habitual systems attending to the details, while thinking about something completely unrelated.

LikeLiked by 1 person

When we finished the grass cutting, utterly unaware that the entire yard is now done, were we conscious of cutting the grass?

LikeLiked by 1 person

I didn’t mean we could do the whole grass cutting job without ever being conscious of it, just that for a lot of the process, our mind can wander. We definitely seem conscious of it at the beginning, end, and when having to navigate around that damn flowerbed, or that spot where the wasps are.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Of course. Edge detection, or deltas that rise above the constant din.

LikeLiked by 1 person

It is only half the battle to point out that “gathering data about p-consciousness, … any data gathered has to come through a-consciousness.” If we interpret p-consciousness as qualia, in the original sense of qualities of perception, then there can be a-consciousness of X without distinctive p-consciousness. Specifically, when X is a belief. My belief that Ouagadougou is the capital of Burkina Faso is phenomenally just like my belief that Lisbon is the capital of Portugal. A city I’ve never seen is the capital of a country I’ve never seen – these are just two bland facts in my database.

By studying phenomenally distinctive states (e.g. hot-cold perception, smells, colors) in contrast to phenomenally undistinguished states (most beliefs), we might learn something about the implementation of phenomenal consciousness in the brain.

This also potentially allows us to steer a course between:

Suppose we find that when sensations are current targets of access processes, all sense modalities show processes of type P. Accessing boring beliefs does not activate Ps. Also suppose that Ps sometimes appear and sometimes not, when sounds enter the ears without current access; and when Ps do appear, you get an accuracy boost like the Israeli scientists found. Suppose further testing raises the level of accuracy of the No-Con trials to significant but small. Then I think it would be reasonable to infer that phenomenal consciousness is broader than (2) implies, but narrower than (3).

LikeLiked by 1 person

A lot depends on how we define “belief”. Eric Schwitzgebel defines it as a disposition to act in a certain way. I can see that having no mental imagery associated with it. But it seems harder to think about a belief, or what we think is a belief, without it, even for purely fictitious entities.

For example, on the capitals you mentioned, I’ve never been to either of them either. But even in the case of the first one, which I’d never heard of before, I still had some imagery pop up on reading the names you listed, even if just fleeting generic city-ness and a capital star on a generic hazy country map. (The imagery congealed a little bit when I looked up the west African country.)

So the question is, can we contemplate a belief without any imagery? This is difficult, because to say, “Don’t think of an image when thinking about this,” is to summon imagery, at least for me.

There are some theories that posit something like the P you describe. Victor Lamme’s recurrent processing theory is the most famous. His take is that anything with recurrent processing is conscious, even if we’re not aware of it. Dennett and Cohen also mention Semir Zeki’s microconsciousness theory which posits consciousness at all levels of neural processing, and something called coalitions of neurons put forth by Koch and Tononi (not sure if this is related to IIT). They criticize all of these theories for not really explaining why any of these proposed Ps would be associated with actual experience. But they’re coming at it from a strong functionalist perspective.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I sort-of agree with Schwitzgebel, or maybe totally, depending how one interprets the claim. From my point of view you have to combine beliefs with goals or desires first, then you get behavior. And, this probably won’t surprise you, but I really like Victor Lamme’s work.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I am pretty sure you are right that Dennett would strongly disagree. And I think he would be right to do so. What I take from him is the realisation that consciousness (of any kind) is a construct, assembled and re-assembled from the on-going flow of brain states, as appropriate for maximising our handle on the world we are in — and it is a part of that internal flow too. For my money, the supposed distinction between access and phenomenal consciousness is a matter of semantics, rather than of fact.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I actually did dig up that Dennett paper, and didn’t see anything that would imply him and Cohen agree, at least not without aggressively misinterpreting the examples they offer.

On the distinction, that’s my take as well. If we take “phenomenal” to mean consciousness as it seems to us, then seeing that as separate from access mechanics is making the category mistake Gilbert Ryle identified, of confusing the whole as something separate from the components and their interactions.

LikeLike

The good old mereological fallacy, sure — still alive and well. 🙂 Panpsychism thrives on it.

But I suspect the problem here is more to do with the thoroughly mistaken notion of “phenomenal consciousness” as some sort of representation, however idiosyncratic, of “what there is”. Whereas, if one takes evolution seriously, one must accept that consciousness homes in on “what there is” only in service to utility. Our phenomenal experience is a construct, not a representation. As such it cannot be separated from access mechanisms of the mind.

LikeLike

Good point on the mereological fallacy.

Definitely something like redness isn’t a representation of light waves (as many suppose), but a representation of what that light reflecting off of something mean for us. Of course, as you note, that applies to everything. Our perception of reality is always in terms of what we need from it, which can shift depending on our homeostatic and mental states.

LikeLike

“Whereas, if one takes evolution seriously, one must accept that consciousness homes in on “what there is” only in service to utility”.

I used to think that particularly when I was enthusiastic about Donald Hoffman. However, for consciousness to be any utility, it must preserve the relationships of the things in the world. If there is no regularity or our consciousness doesn’t map to the regularity, there is no way for consciousness to aid in acting in an evolutionary advantageous manner.

LikeLike

We do not actually disagree. Consciousness homes in on “what there is”only in service of utility — which it does, of course, to a sufficient degree. But what is sufficient, is very much context dependent. As our host puts it ” Our perception of reality is always in terms of what we need from it, which can shift depending on our homeostatic and mental states.” Thus correspondence with noumenal reality is an important factor, but by no means the only factor.

LikeLiked by 1 person

There is a difference because once relationships are constructed to match the world then a representation or model has been created.

LikeLike

In which case we may be arguing semantics. Is a cubist portrait a representation? Could our understanding of water be construed as a representation of electricity? Depends on what you mean by a representation. If any partial reconstruction of relationships will do, then yes, you are right and we can (no, not really! :-)) discuss at what point a representation slides into an analogy.

But your response suggests a certain misunderstanding. I probably should not have used “representation” in contradistinction to “construction”. My exchange with our host was not about the fallacy of representationalism but of any form of perceptual realism — the notion that our perception of what there is necessarily corresponds to what there is.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I am talking about a physical representation or model of the world that enables action within it. The word “construction” implies an arbitrariness – the idea that it could be anything. But the parts of the model are constrained by their relationships with the other parts. They can’t be simply anything without rendering a model that would be fatal to the organism.

LikeLike

“The word „construction“ implies an arbitrariness – the idea that it could be anything.”? A bridge is a construct, but it cannot be a well, even though a there is a lot of arbitrariness (from the functional PoV) as to its specifics.

And there is, indeed, arbitrariness in our perception of the world. E.g. we perceive colours in a circular arrangement, with violet bordering purple, which does not actually correspond to physical reality. To our touch, metal feels colder than wood when both are the same temperature. Natural variability of smell receptors strongly affects what smells people can perceive or find pleasant or unpleasant. Shadows in a snowy landscape can look blue when they are not. Does any of it make our perception in any way non-functional?

LikeLike

What is the physical reality for arranging colors? A square, a line?

There is none except through the representation in consciousness. But I don’t normally think of it as a circle unless I pull out a color wheel to improve my pathetic artistic sense to assist in decorating or painting.

LikeLike

” the notion that our perception of what there is necessarily corresponds to what there is”

It is easy to think that there is objective way things are, a way things would seem if we could break through the limitations of consciousness or knowledge. But there isn’t. Just like there isn’t an objective space or time as envisioned in the Newtonian world, there isn’t an objective way things are. We only know how things are through perception and thought. The reason in both physics and neuroscience is that we are a part of the world, as is everything else, so there is nothing that can stand outside the world to gain an objective view. We can only perceive what it is relative to our selves in the world.

LikeLike

“What is the physical reality for arranging colors? A square, a line?”

It is, indeed, arbitrary. My point is, it is closed. Purple and violet appear to us adjacent — that is way more similar than, say, red and green. What feature of the world is being tracked thereby?

“We can only perceive what it is relative to our selves in the world.”

I wouldn’t have guessed. 🙂 But in what way does this observation support your objections to the notion that our perception is a construct?

LikeLike

Probably everything is a construct but a perception is also a representation.

LikeLike

“Probably everything is a construct but a perception is also a representation.”

In which case you are either not using “representation” in its normal philosophical sense (see e.g. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/consciousness-representational/) or you think (mistakenly) that there is no alternative to representational view of minds (see ditto).

LikeLike

Since what you link has about 25 different flavors of the idea each with 10 nuances, it is hard to take seriously the idea the term has any “normal” usage philosophically.

LikeLike

And bridges come in many designs, shapes and sizes. This does not mean that there is no core concept of “a bridge”. You cannot expect to meaningfully join a conversation about bridges if by “a bridge” you mean “a well”.

It is because philosophers share the core concept of representation in the context of philosophy of mind, that they can indulge in their manifold disagreements as for the details, relevance, or even existence of representations in mental processes. There was a reason I was pointing you at that Stanford article. Did you actually look at it?

LikeLike

I honestly didn’t look at it very much once I read this:

Indeed, there are now multiple representational theories of consciousness, corresponding to different uses of the term “conscious,” each attempting to explain the corresponding phenomenon in terms of representation.

I immediately began to wonder which one of the four was the “normal” one. Maybe you can clarify.

I did go far enough to read the Bertie argument which is completely fallacious reasoning as any kind of attempt to disprove materialism.

I’m not sure where exactly you think I am coming from. But maybe you are having a problem because I am arguing that perception is a physical representation as are all representations as far as I can tell.

LikeLike

Frankly from their own write-up I can’t tell exactly what they did in these trials.

It seems like the subjects had some practice rounds with various sounds. By the time you get to the experiment, some people may simply discounting the pink noise as not something the researcher was looking for. Even tho0ugh they hear, they do not report it. Others may think the researchers expect them to report the noise. Others still may be regarding it as background and effectively doesn’t count.

I would be dubious of any conclusion.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I know what you mean. I actually found their Methods section largely impenetrable. Most of what I wrote in the post comes from the Introduction and Discussion sections.

And I had the same concerns about how the test subjects might interpret the noise. I think they did postmortem interviews, and people in the P-Trial group characterized themselves as “realizing” they had been hearing the noise. So I gave the authors the benefit of the doubt there. But if I thought the results were actually significant, I would definitely want to see them replicated by other teams looking out for those issues.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Good to know you had problem understanding what they did too. I was beginning to think I should retire from trying to understand this stuff.

LikeLiked by 1 person

The novelty of this study is that it investigates the question of whether our phenomenal experience is richer than what we can remember and report, not by means of experiments on visual perception but on auditory perception.

As far as I know, all studies on this question have featured experiments on visual perception. Many of these studies claim to have provided evidence that visual experience overflows the capacity of the attentional and working memory systems, simply that we see more than we can report. However, as Ian Phillips has pointed out, the data from these studies are also compatible with the opposite view.

Google Scholar

I must admit that I did not fully understand the study design of Mudrik et al., but it seems very daring to draw far-reaching conclusions from the answers of the 40 participants who had at least four P-trials, no matter how many R-packages the authors used. I think that Ian Phillips’ reasoning could also be made about this study.

I think the perceptual hierarchy of consciousness you propose is a reasonable approach, but I would prefer to put it in place 1: “Conscious content results from self-monitoring of access processes”, which is in line with higher-order theories.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks for the Ian Phillips link. I’ll check it out. Not that I need convincing on that point. There just doesn’t seem any way around the access mechanisms for verifying that something is conscious. Even the no-report paradigms still require it, just with a time shift. It’s William James’ old dilemma of turning up the light to get a better look at the dark.

The methods sections is pretty difficult. I mostly constructed the narrative in the post from the Introduction and Discussion sections. But I imagine a professional really has to get into those weeds. And even allowing that there aren’t any methodological issues, I agree they overinterpreted the results.

The perceptual hierarchy can be adjusted relative to whichever perception we think is the crucial one. For the post, I was including self monitoring of access processes as part of overall access processing. But we could adjust it as follows:

1. The results of self monitoring

2. The current target of self monitoring

3. Everything that could be self monitored

4. Everything else

LikeLiked by 1 person

Let me take a stab at explaining this from a temporal/wave dynamics view. Probably nothing original.

If you have multiple waves, small waves become subsumed into larger waves and are not accessible. Larger waves make bigger impressions than smaller ones and are more likely to be able to be recalled. Size is probably mostly controlled by strength of stimulus.

A larger wave will tend to drown out smaller waves. However, remnants of even small waves may still appear on the surface if the large waves is not too large. A tsunami, of course, will wipe out all the other waves. It is all relative to size of stimulus, degree of boosting, and what else is going on at the same time.

During attentive processes, however, the brain generates it own waves (the traveling waves? in that article I linked in one of my posts) to boost the signal of anticipated stimulus so the wave is larger than it would be on the basis of stimulus alone. These waves probably are passing over and through exactly the areas that would process the anticipated stimulus.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for the explanation. The part about anticipation of a stimulus increasing activity for the region in which the stimulus itself would cause activity matches what I read about attention in mainstream neuroscience textbooks.

My only note would be about the size of the wave. The largest wave I’ve read about, the P300, is a positive one, which means it’s inhibitory, suppressing the propagation of signals for all but a small portion of the affected regions. It’s the signals that aren’t suppressed which appear to be the causally relevant ones. (This is the idea of the global ignition for GNWT, which seems increasingly shaky to me, but the wave definitely happens, and it’s not controversial in attention studies.) I could see an interpretation of that wave as still being about that causally relevant signal, about its effects on the wider system, but the story seems a bit more nuanced than just saying the biggest wave wins.

The waves seem like broad indicators of what’s going on, but to really understand, it seems like we have to get into the details of those waves, and how and why they’re propagating at a neuron by neuron level. Which of course is far more difficult. Unless I’m missing something.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, the devil of understanding this completely will be in the details.

I wouldn’t expect the traveling waves possibly associated with attention would be the only types of waves or the only type of function waves perform. The resting state waves, according to my understanding of Northoff, may maintain some base level of consciousness. They likely would integrate experience on multiple timescales from milliseconds, seconds, to hours.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Actually P300 (which I just looked up since I wasn’t ware of it) may help confirm the general approach I was taking.

“The P300 wave is an event-related brain potential measured using electroencephalography (EEG). P300 refers to a spike in activity approximately 300ms following presentation of the target stimulus, which is alternated with standard stimuli to create an ‘oddball’ paradigm, which is most commonly auditory. In this paradigm, the subject must respond only to the infrequent target stimulus rather than the frequent standard stimulus”

https://library.neura.edu.au/schizophrenia/physical-features/functional-changes/electrophysiology/p300/index.html#:~:text=The%20P300%20wave%20is%20an,which%20is%20most%20commonly%20auditory.

In normal attention, you are anticipating a stimulus and need to prime the brain area where it will process to boost the signal. In P300, you are trying to avoid/ignore a stimulus so you need to prime the area for overlooking the stimulus by reducing the signal.

LikeLiked by 1 person

That’s a good point. The P300 is a response to external stimuli. It’s almost certainly not the only path to information having causal dominance of the cortex. In my mind, that’s always been the weakness of Dehaene’s specific model. It’s too specific to a particular path to awareness. I think global workspace theories should allow for alternate on ramps. (Of course, looking at specific on ramps is much easier to measure, but no one ever promised this would be easy.)

LikeLiked by 1 person

2 cents, briefly: Seems we’re playing with words and definitions, methods and analysis. In the end, as usual – who decides? For sure there are levels, or degrees, of conscious awareness. At the highest level would be Self-awareness. But again, who decides? Your analyst?

How aware is a creature of why they do what they do, or their behavior?

Staying with humans, I think, awareness, no matter the metric, would distribute along a bell curve. Individuals would have a range of reaction depending on situational demands. Collectively, the varying levels of awareness would enhance the group’s (or tribe’s) survival chances. Important stimulus would be noticed by someone; then an “argument” would ensue and a decision made.

We humans may be beyond that now. Or, at an impasse. Uh-oh.

LikeLiked by 1 person

My take is we all decide for ourselves. Consciousness is in the eye of the beholder. As you note, we can reasonably settle the question of whether another system introspects, has imaginative deliberation, goal directed behavior that can involve overriding initial impulses, etc. Whether it has consciousness is only a meaningful answer once we decide which of those (or other) specific capabilities we’re using the word “consciousness” to refers to.

LikeLike

It might be interesting to note that lead author Liad Mulik was also involved in the ‘Adversarial’ search for neural basis of consciousness.

As a result, the study also addresses the issue of whether the neural correlates of consciousness (NCCs) typically involve only posterior cortical areas or also include frontal regions. No report paradigms that supposedly show that the content of an experience is much larger than what can be reported by a subject at any given moment, implying that there is p-consciousness without a-consciousness. are seen by IIT proponents as evidence that the NCCs are primarily located in a posterior cortical “hot zone” that includes sensory areas but not the prefrontal cortex.

This is what the IIT contends, employing, lets say, a very idiosyncratic theoretical framework, claiming to start from the essential properties of phenomenal experience, from which the requirements for the physical substrate of consciousness could be derived.

According to local theories of consciousness such as IIT and RPT neuronal activity in sensory cortices solely determines the subjective character of an experience. RPT argues that consciousness does not necessarily require the involvement of the entire fronto-parietal network, but posterior cortical areas are sufficient as long as feedback connection instantiate sufficient recurrent interactions. In this view, local recurrent interactions in posterior cortex support phenomenal consciousness, whereas global reentry including prefrontal cortex is needed only for access consciousness.

However, I don’t think that interpreting the experimental results this way is valid.

As Joseph LeDoux argues in his very readable book The Deep History of Ourselves (chapter 53), it is implausible to separate phenomenal consciousness from the ability to know what we see and to report that experience. The neural findings put forward by proponents of local theories are more about the unconscious perceptual processing that controls our behaviour than about an actual state of phenomenal consciousness. As he puts it: If you don’t know something is there, you can hardly experience it consciously.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Interesting on Mulik. I didn’t realize that. Thanks!

I agree on everything you write here. One of the things that I’ve found annoying since my earliest days reading about the mind, is how many people want to make assumptions that eschew possible grounded explanations. They then take what’s left and write about how mysterious and unfathomable it is. Well yes, but only because they’ve preemptively ruled out the pragmatic explanations. If I ban any discussion of recipe ingredients and cooking processes, then a finished pizza starts to look metaphysically mysterious.

If the sensory cortices are sufficient for subjective experience, then it’s a very mysterious problem. The problem is no one can establish that sufficiency without involving the rest of the brain, but the rest of the brain, they insist, can’t be part of the explanation.

Occasionally I wonder if consciousness, in and of itself, is worth bothering with scientifically. Maybe neuroscientists should just focus on specific capabilities, like discrimination, memory, reportability, etc, and let the philosophers make whatever they want from it for consciousness.

LikeLike

The question is how can you measure P-consciousness in the absence of A-consc? If P-c is an epiphenomenal excretion of neural activity then it has no independent effect that can be measured, but if it has a seperate currently unkown top-down effect then it can be measured. Perhaps under normal conditions P-c can effect both cognitive activity and motor activity so that one can have an experience of say a red patch and then report it. But when cognitive access is impaired then one can neither report nor remember the P-event. But if P also has some effect on motor output maybe that can be measured seperately. So for instance, in blindsight perhaps the subject is P-c and thus acts to avoid obstacles but is not A-c so has no cognitive awareness of how he did it.

LikeLiked by 1 person

The trick is separating the effects of p-consciousness from those of unconscious processes, which also have affects on motor output. If they can’t report on it, even retrospectively, then how do we know they were conscious of it?

LikeLike

It is very difficult to tell since they (p&a) are normally integrated together which is why cases like blindsight when they come apart are interesting. To me blindsight says that the brainstem is p-con (as Solms suggested) and can operate and move while higher cognition has no visual cortex to tell the language center that it saw anything.

We know that p-con is very important since it appears that when it is absent we are in bed and not making dinner plans, driving the car and doing the laundary. Zombies are overhyped possibilities that dont really exist in humans. We also know that a great deal of what we do is done automatically, you may say unconsciously or robotically. My guess is that although the motor operations of the frontal cortex, etc can operate very efficiently, for instance climbing stairs, it doesnt really know what to do (go up the stairs) so it is always under at least the high level supervision of p-consc which is making those decisions which seem to start activity.

LikeLike

I agree about zombies. They imply consciousness is an epiphenomenon in the philosophical sense of having no causal role, which if true would put it outside of evolution. It’s a thought experiment which just presupposes what it purports to demonstrate: dualism.

Setting aside the question of p-consciousness, mainstream neuroscience’s understanding of the functionality is somewhat reversed from what you describe. Usually the brainstem is understood to provide innate reflexive reactions, such as ducking under an incoming object. The basal ganglia handles habitual responses, like routine driving or climbing stairs. And the frontal cortex handles novelty and planning, like deciding how to drive around an obstacle in the road, whether to climb the stairs, or what we’re going to do when we reach the top.

LikeLike

What function I am thinking of in the upper brainstem is action and decision making at a felt gut level. Certainly the frontal cortex does planning and begins actions, but in cases where there are several possible alternative actions with different likely posible consequences, those ideas may be sent to the midbrain where such a gut level decision is made. Although this is the minority view eminent neuro scientists such as Wilder Penfield, Bjorn Merker and Antonio Damasio have endorsed this model or something similar.

LikeLike

I don’t think that quite captures Merker or Damasio’s positions. Both admit that action selection happens throughout the stack. But Merker in particular argues that the final integration for action that happens in the brainstem is consciousness. But he seems to overlook integration for habitual action, or integration for planning, which happen in the higher level regions. And Damasio, at least in the material I’ve read from him, allows that aspects of consciousness may happen in the brainstem, but he doesn’t see it as the whole show. (Merker, in his seminal paper, took the more absolutist position, but then seemed to back off in his response to the commentary.)

I did a post on Merker’s paper a few years ago: https://selfawarepatterns.com/2019/02/10/is-the-brainstem-conscious/

LikeLike