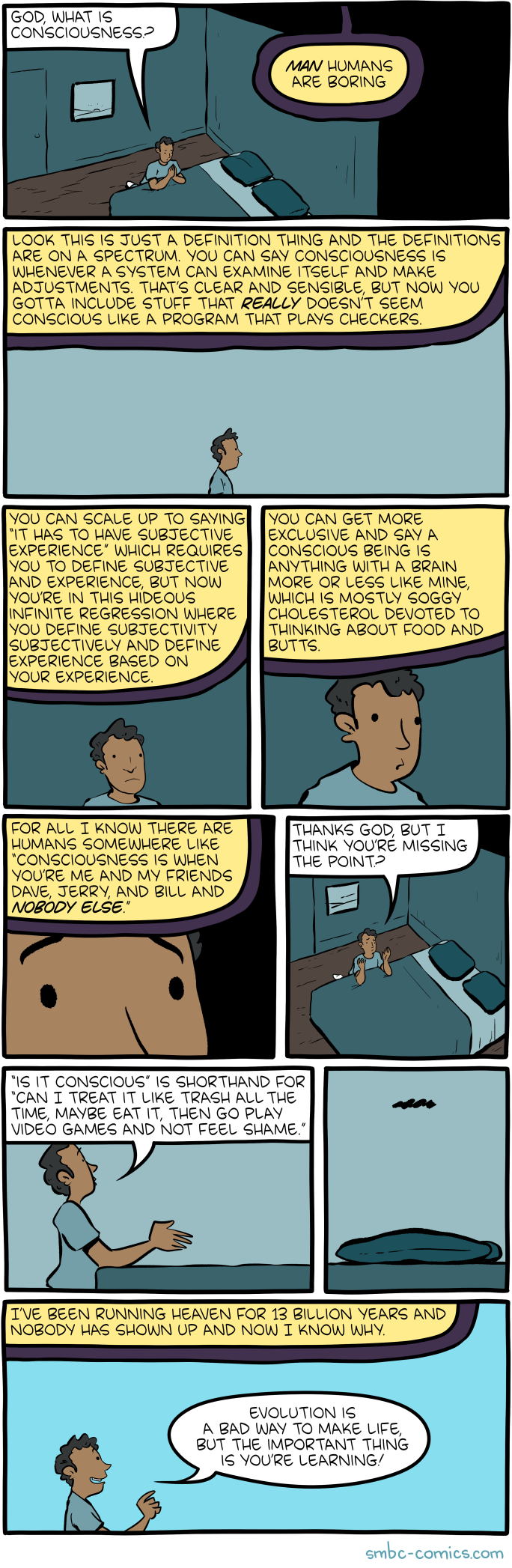

Zach Weinersmith is a man after my own heart when it comes to consciousness, as today’s Saturday Morning Breakfast Cereal shows. As the consciousness is in the eye of the beholder and hierarchy of definitions guy, I feel this comic. It also resonates with Jacy Reese Anthis’ conscious semanticism outlook.

As usual, I’m sure there won’t be any controversy here at all. But if you do disagree, what do you think God’s answer should have been?

Note: Weinersmith has a new book coming out via Kickstarter, which looks pretty interesting.

You know my answer to the first question (look for the common denominator), but I’d be interested to see your answers to the other questions:

1. How do you define subjectivity?

2. How do you define experience?

3. What is/should be the relation between consciousness and moral patiency (what difference should it make whether something is conscious in how we treat it/them)?

*

LikeLiked by 1 person

The big issue with the common denominator is what God said in panel 2, you end up labeling a lot of stuff conscious that doesn’t really seem so. I know you’re comfortable biting that bullet, but most people aren’t.

In defining subjectivity and experience, I think the trick is not trying to see them as something distinct from the upstream causes and downstream effects, but as those causal chains.

1. Subjectivity is modeling the world and oneself from the perspective of one’s sensory and information processing mechanisms and innate and previously learned models.

2. Experience is the construction and fine tuning of those models.

3. I’m not a moral realist, and obviously I don’t buy consciousness as a natural kind, so to me the relation is whatever we collectively decide it to be. But I think in most people’s minds, there’s a one to one relationship.

LikeLike

So we’re agreed on 1 and 2.

As for 3, you may have noticed I have become interested in the basis of morality and have concluded that said basis involves cooperation w/ goals. Such cooperation is how certain things can be done beyond what individuals can do. Given that the common denominator of consciousness (Psychule) specifically requires a goal for the interpretation of a signal, I’m inclined to conclude that the reason of the association of consciousness w/ moral patiency is that consciousness implies goals, but the reverse is not necessarily the case. Want to take a step into these waters?

*

LikeLiked by 1 person

Not sure. It seems like many of the worst atrocities in history involved a lot of cooperation with goals. Genocide, for example, requires extensive cooperation within a state or society. You might say those goals weren’t right because they weren’t cooperating with the goals of the victims. But what about the goals of something like the COVID-19 virus, whose “goal” appears to be to reproduce far and wide in our bodies? Or the goals of mosquitoes who want to bite lots of people, but which we resist because it’s painful and they carry disease?

That’s the issue I’ve seen with every attempt to ground morality in a single principle. It always leads to cases where we have to use our common sense to make exceptions. But if we’re going to do that, use our intuitions to override the reasoning, then the reasoning seems redundant. I’m not saying consequentialist, Kantian, and other major theory reasoning isn’t useful in helping us think through things, but they never seem to work consistently. We still have to evaluate the results according to our innate and learned social intuitions, which will always vary between people and societies.

LikeLike

So there’s two things going on here.

1. There’s an objective reason we have a sense of morality: it was selected by nature to advance the existence of life

2. We individually choose our values/morality, and selection then works on our choices at an individual and cultural level

So at level 1, there is an ongoing tension between the 2 major options which I call cooperation v. domination. In the prisoner’s dilemma, they’re called cooperation and defection. Eric Schwitzgebel calls them sweethearts and jerks. Cooperation lets groups do things which individuals cannot, but within a group of cooperators the dominators have the advantage. Your example of atrocities is an example of a group consisting internally of cooperators, but among groups (so, a higher level) that group is dominating, instead of cooperating.

At level 2, the individual (or individual group) does not simply cooperate with every goal it recognizes. The individual has to place a relative value on each of its own goals as well as those of the goals it recognizes in others. Some of those goals it sees in others can have negative values, which is why it’s ok to lie to the potential killer at the door looking for a particular victim hiding in your house.

So we know all animals and plants have the goal of survival, but we place different values on individuals, and we tend to place higher values on more intelligent animals. And sometimes we place higher values on the goal of not suffering, which is why it seems okay to eat certain animals as long as they are not raised in horrible conditions.

Make sense so far?

*

LikeLike

The question that jumps to mind is, how are we deciding the value to assign to the goals of others? Is it just in how much it aligns with our own goals (some of which may be pro-social)? If so, then we seem to be working in game theory. I have no issue with that, but it doesn’t seem to provide any universal truths, just which strategy is best in particular scenarios (such as cooperate-then-tit-for-tat being useful for recurring interactions, but not necessarily one time events).

If it isn’t alignment, then are we just falling back on evolved and indoctrinated intuitions? If so, then how do we avoid the conclusion I noted above that we’re only following the reasoning as long it accords with those intuitions, or maybe to justify those intuitions after the fact?

LikeLike

How we set values is a complex subject worthy of extensive study. There’s evolved moral intuition, indoctrination, and rationalization (game theory?). And again, in each there will be tension between dominance and cooperation. If you are only setting positive values to goals that align with your own, you’re tending towards dominance. Those who are emphasizing the “greater good” are tending towards cooperation. In the end you choose your rules of thumb and Darwin sorts you out.

*

LikeLike

Right, but dominance could win in many cases, even when it’s widely recognized to be an immoral result. We can’t look to evolution for moral clarifications. In the end, we can’t discover the rules for living like we do the rules of matter and energy. We have to collectively decide what they are.

LikeLike

Of course dominance does win in many cases. See Hitler, Trump, Putin. But on the whole those cases get selected out, sooner (Trump) or later (Putin).

In the end we can’t discover the (best) rules for living, just like we can’t discover the best explanation of matter and energy, but we can discover better rules for living just like we discover better rules for matter and energy. And then we collectively decide whether they are better, and some will disregard whatever that collective decision turns out to be.

*

LikeLike

Sounds like we’re closer than I thought. Good deal.

My only remaining caution would be that the “later” part of “sooner or later” can involve a lot of suffering. John Meynard Keynes used to say, in response to classical economists who insisted it all works out for the best in the long run, that “in the long run” we’re all dead.

LikeLike

It is a bit surprising that the story does not consider God as aware about the concept of representation. The answer could have been:

Human consciousness is based on self-consciousness. Self- consciousness is the capability for an agent to represent its own entity as existing in the environment like it can represent other entities existing in the environment. Such representation of one’s own entity by an agent is a self-representation.

Representations are here networks of meanings which are meaningful relatively to the constraints the agent has to satisfy to maintain its nature (stay alive, act as programmed, ..) ( https://philpapers.org/rec/MENITA-7 )

A self-conscious agent can think about its own entity (=> introspection, phenomenal consciousness).

A self-conscious agent can use representations of its own entity for actions (free will).

LikeLiked by 1 person

I think the second panel gets into a very abbreviated version of that. It doesn’t mention representations, but I feel like they’re implied in “a system can examine itself and make adjustments”. How can the system examine itself, and think about what needs adjusting without representations? (I’m using a broad definition of “representation” with this question. Obviously if we take a sufficiently narrow one, then there’s no guarantee that version is used.)

LikeLike

The wording « A system that can examine itself » implicitly introduces a « self » as part of the system. But what is a self?… As far as I know it is a still open philosophical question and using it as a given to explain self-consciousness is like hiding a problem by another problem.

This is why I prefer the wording « entity »:

Self- consciousness is the capability for an agent to represent its own entity as existing in the environment like it can represent other entities existing in the environment.

LikeLiked by 1 person

The limitations of language. I don’t usually think of “it” plus “self”, as in “itself” as necessarily implying the same kind of self people mean when they use the word alone. For example, I might say my laptop rebooted itself without implying any kind of conscious self being there.

Of course, the question is what distinguishes the self we normally mean by “itself” and the one we mean by “ourselves”. And I definitely agree that we have to be careful not to take what we’re trying to explain as a component of the supposed explanation.

LikeLike

You are right. We should be cautious with the way we use words. The concept of self depends on the context. A computer « rebooting itself » has no self. As said, the concept of self at human level is a philosophical problem. But introducing that concept at a biological level can be an interesting entry point : no need to care about self-consciousness. Only to look at the possibility to associate a self to an entity maintaining its status in a far from thermodynamic equilibrium. A pre-biotic entry point (wip continuation of : https://philpapers.org/rec/MENICA-2 ).

LikeLiked by 1 person

Wow, the part about “is it conscious?” being shorthand for “can I treat it like trash?” hits hard for me. I do think that’s an oversimplification and that there’s more to the discussion than just that, and yet that does ring true in a way that makes me uncomfortable.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yeah, this strip actually covers a lot of philosophy, but in a brutally abridged fashion. (Which fits, since Weinersmith likes putting out books with titles of the form: “X Abridged Beyond the Point of Usefulness”.)

LikeLike

as for me, i got no questions. I like the comic strip

LikeLiked by 1 person

Both you and the cartoonist may be misunderstanding something.

The question “What is consciousness?” is ambiguous. Judging from the proposed answers to the question by the cartoon character, what is being asked isn’t a definition but an explanation.

LikeLiked by 1 person

But an explanation for what? And what would be the explanation?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Once you’re into brains and deep into subjective experience topics and whether you can eat it, you’re well beyond definition.

The question frequently being “heard” when “What is consciousness?” asked is “How do you explain consciousness?” because people think that it is a mystery of some sort.

“Definition’, by definition, involves using one or more words to describe another word. So, no matter what you are defining, there is a degree of circularity built into it. Ultimately you have to trust that two people when they hear a definition have a similar frame of reference to relate the descriptive words. Words frequently are somewhat fuzzy also. Normally a box would not be thought a table, but if I moved and the furniture hadn’t arrived, I might set up a box and call it a “table” and you would likely understand.

So the common frame of reference is you and I both awake each day and can interact with the world because we seem to have an awareness of it.

It is somewhat like experience of the color blue. Even if we had never seen it before, we could see the color blue and agree to call it “blue” and this would work for any other object that was blue. But that, of course, could be somewhat fuzzy, because I might see a color that you might call “blue” but I would call “violet”.

This common frame of reference definition is exactly what we would mean if a football player was knocked unconscious, carted off the field, and later we were told he was awake, talking, could move his legs, etc. The CFR definition tells us that another organism likely is having phenomenal experience in some way similar to what emerges in ourselves everyday when we wake up, can talk, can move our legs, etc. much and to a similar degree in how we agree on “blue”.

Explaining it? Oh, it’s definitely the brain in my view. I don’t want to go out of limb.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks. I agree with much, if not all of this. One of the banes of philosophical discussion is that language is always fuzzy. (Science often falls back on equations to get past this, but in complex systems even variables can be ambiguous.)

A question with the CFR definition is how much we can mess with it and still retain the intuitive sense that there’s something conscious there. For example, if it’s a robot waking up, moving its appendages, talking, and agreeing on blue, do we count it as conscious? A while back I would have said most people would say no, but there’s been a lot of people tempted to think LLMs are conscious (even though they only have a small slice of that behavior). It feels safe to say they’re still a minority, but I wonder if they would be if a system displayed everything you list here.

Overall though, and to the point of the comic, it’s not clear there’s any fact of the matter here. Your view on what is crucial for the CFR is likely different from mine. And I don’t know of any empirical test we could do to establish one answer more right or wrong than the other.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Glad we mostly agree.

The dilemma to me is that the only sort of behavior until recently (and current examples otherwise are debatable) the only entities that could be described as conscious in that they display a nuance of behavior, capability of learning, and actual intelligent agency in the physical world are living organisms with brains. So the evidence so far is that brains are necessary. When a circuit does what a brain does needs a theory.

LikeLiked by 1 person

For me, when a machine does what a brains does isn’t a binary true or false distinction. Computers already guide robot behavior, which is part of what brains do. They also monitor and attempt to regulate energy budgets (like when my phone starts getting insistent about being charged). Of course, brains still have a large list of capabilities no machine can do yet. So it’s not when they will do what brains do, but how much of what brains do is necessary.

But this is that difference in how much of the CFR we see as necessary.

LikeLiked by 1 person

The CFR ultimately must resolve to mental experience at some point.

But let’s say we agree that a machine does everything a human does, is indistinguishable from a human, and so we declare it conscious. What has been accomplished?

Actually nothing as far as explaining how aware organisms work.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’d say if we managed to build such a machine, assuming we understand it, we would have figured out a lot about how aware organisms work. Some might argue that building consciousness doesn’t mean understanding it, but at that point I’m okay leaving whatever’s left for the metaphysicians.

LikeLiked by 1 person

“we would have figured out a lot about how aware organisms work”

Since there is really no great barrier to building such a human-like machine now – current robotics, some tweaks to neural nets, better sensors – I would think we would know a great deal more about human brains work if that were any additional value for the effort. We already had the guy at Google claiming its software was conscious. It is much like landing on the moon in the early sixties. It would be a challenge and require some technology gaps to be filled to reach the goal by the end of the decade but there were no fundamental discoveries needed. I think we are pretty much exactly at that place now with human-like machines. Maybe a decade or less away.

But where are we with neuroscience? I don’t see adding more fMRI studies suddenly resulting in a breakthrough. I don’t see how silicon chips and software will lead to to it either. The breakthrough could still happen in a decade. I think it will happen eventually, but there is no clear path to it happening from where we are today. We sill have a knowledge gap in neuroscience; whereas, the path for human-like machine is straightforward from where we are already at.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I actually remain skeptical about where we are with AI, or that the path is that straightforward. I think people are reading too much into the chatbots, which I still don’t find that hard to trip up. (ChatGPT 4 is reportedly degrading, which is interesting.) We still don’t have fully self driving cars, or even a robot that can hunt and forage as well as a honey bee, or your typical fish. I say this as someone who definitely thinks that progress will eventually be real, but don’t see it yet.

Most neuroscientists say we’re at least a century away from a full understanding of the brain. AI research has the promise of possibly accelerating that. As we figure out a way to do cognition like stuff with technology, it can provide working hypotheses to test in biology. And of course biology remains an inspiration for engineering. A lot of research in the two fields is in a feedback loop with each other, which seems like a fruitful path. But still a long road ahead.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I think the human-like robot is really pretty close.

But I think there is a problem applying it to understanding how brains work.

Let’s me assume that neural nets, which were modeled off of out understanding about how neurons worked, might actually model well what brains do. This is where there could be some crossover of knowledge from AI science and neuroscience.

In that case, human robots will basically only need to be mechanical, material, and electrical engineering for the body with a computer and software driver. So once you marry the body with the driver, you have a human-like robot.

The problem with brains is they are not a computer/software driver. The brain is the neural net. It is not a wet mass of neurons running a program. It is hardware and software in one. AI can model what it does with software neural nets (hence, produce a simulacrum of a human) but what would be needed is to build a hardware neural net, possibly one that is self-modifying.

At the point of realizing a neural net in actual material, if and when it happens, we may have created something that is conscious but we may not still have a comprehensive understanding about exactly how it works.

LikeLiked by 2 people

I think it’s pretty well recognized that software neural nets used in machine learning algorithms are much simpler than the biological versions. Strangely enough, I’ve heard of software neural nets being used to model the operations of one biological neuron. There’s just a lot going on in biological neurons than the simplified nodes in software.

On your point about creating a physical neural net, I think this is the difference between functionalism and other outlooks. The functionalist expects that if we can recreate the functionality in a software neural net (or something else), then we’ll be there. The only reason a physical nerve net might be required is if the specific substrate provides some functionality that can’t be realized with any other material. That’s not inconceivable, but I don’t see any data driving it, at least not yet. Even if EM fields are involved, if we can reproduce the relevant causality of those fields, I think we’ll still be good.

One thing the physical instantiation provides is the ability to work at slower speeds. It makes up for the relative pokiness of biological signaling with massive parallelism. In software, that parallelism is simulated by the processor running a million times faster. Of course, if you crowd sourced a software neural net across enough processors running in parallel, you might get the best of both worlds. But I’m agnostic on what the best architecture will turn out to be. (I suspect there will be numerous.)

But as I noted above, even when we get to the point of being able to reproduce the behavior of a conscious system, many will say we still haven’t explained phenomenal properties, even if everyone agrees the system we built has them. For some of us, that will be because the concern is misguided. For others, it will continue to be a mystery for philosophers to ponder.

LikeLiked by 1 person

A computer/software has a real world presence of CPU, RAM, interfaces, etc. That is the stuff that actually exists in the material world. The abstract stuff of software cannot

The real world presence of the biological neural net is the brain itself . The brain is the stuff that exists in the material world.

The neural net must have a real world presence to become conscious. It must, in effect, feel itself to exist. It is the model of itself in the world. It can’t be felt if it is not real stuff.

LikeLiked by 2 people

The abstract stuff of software cannot feel because it is not a part of the real material world. [to complete that sentence that got inadvertently erased]

This approach makes consciousness literally material.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I think when comparing systems, we have to compare the whole system, including the stuff it’s composed of, and what the stuff is doing. Of course, the dividing line between substance and process is a matter of convention. What’s a convenient convention at one level of abstraction tends to be different as we go down levels. For example, we might think of a molecule as substance, but at a lower level it’s a process of atoms held together by shared electrons and exchange of photons. We might think of atoms as material, but they’re processes of elementary particles interacting, etc. Eventually we get down to quantum fields, where it’s not clear what the substance is anymore.

I think the best way to think of software is as an action plan, and running software as the hardware following that plan. But it’s always an option to put aspects of the plan in the hardware, as in logic circuits, with gray zones like firmware and microcode. The dividing line between substance and process is different from that in brains, where more of action plan is in the wetware. This gets into the trade offs I discussed above. But what matters, at least for a functionalist, is the functionality of the whole system.

With regards to feeling in particular, it gets into what we think feelings are. I think they’re processes, functionality, automatic reactions of the system subject to evaluation by the system in light of its goals.

What you describe could be considered part of classic materialism, but most people today who would answer to the “materialist” label today are better described as physicalists, where energy, dynamics, and spacetime are also part of the ontology.

Ultimately though, as I’ve said many times, consciousness is in the eye of the beholder, about how much like us a system is, with no strict fact of the matter. If you want to reserve your “like us” conclusion for things like us in substance at a certain level of abstraction, regardless of behavior, I can’t necessarily say it’s wrong. But given people’s reaction so LLMs, I don’t know that that view will stay in the majority.

LikeLiked by 1 person

James, I’m assuming you would consider the classical p-zombie to be conscious, because it would have the same physical brain as yourself. But what about the functional zombie (f-zombie), which has a silicon/computer brain but performs all the same functions. Consider a world populated only with f-zombies, including f-animals. Left to their own devices, they would also develop the idea of consciousness, and perhaps they would conclude that only those with silicon brains have “real” consciousness.

See “They’re made out of meat” — https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7tScAyNaRdQ

*

LikeLiked by 1 person

I don’t consider p-zombies able to exist. An awake human with a working brain would have conscious experience . F-zombies are not conscious at all since their implementation is abstract. The implementation must be instantiated in real matter, such as a brain, and have a real existence in the world to be conscious.

Consciousness is information encapsulated in a physical neural net that forms a concrete model of itself (that is the neural net) in the world. Any machine capable of doing that would be conscious but current computers running programs do not do that.

LikeLike

My reaction to the cartoon was a cross between a smirk and a small laugh. Seriously though, I think it trivializes and ridicules the academic/erudite discussions around what consciousness really is (if it really is anything), the way someone who hasn’t a clue looks and listens in to scientific or philosophical discourse from the outside. As for J.S. Pailly’s comment, I have come across philosophical discussions dealing with treating non-humans (animals, etc) whom we consider conscious to some degree as subjects deserving of moral consideration; i.e., subjects we should treat morally and ethically (don’t cause them needless suffering, don’t eat them, etc). I don’t think the cartoon warrants a serious discussion. I see it more as a comic relief (as appears in some Shakespearian tragedies) to our more serious discussions on the subject of consciousness.

LikeLiked by 1 person

It definitely pays to remember that this is a cartoon, and mostly going for the reaction you had. As I noted above, it’s really abbreviated so much that it’s little more than a gag for anyone not familiar with, or who disagrees with the relevant material. But I detect in these captions a lot of familiarity with that material and an attempt to sneak in some philosophical points. (Based on the social media discussions the author often has, this isn’t a reach.)

Caption 2 hits on metacognitive theories, and their small system vulnerability. The next caption hits the common philosopher move of just defining consciousness as “subjective experience”, and the issues with that. The one after that pokes at biopsychism for its arbitrariness. And the response J.S. Pailly noted, pokes at the often unquestioned relationship between ethics and consciousness.

So a lot covered in lightning fashion. All a joke, but if you’ve never encountered the ideas before, one that might make you think, which is why I like these SMBCs.

LikeLiked by 1 person

God should have said:

Whose permission are you asking with “Can I treat it like trash?” Actually I know whose permission; it’s that of your fellow humans. You’ll have to discuss it with them.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Except humans disagree with each other. (For that matter, so do gods.)

LikeLike

Well yes, that’s why you have to hash it out.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m late to the party, having digested this for a while. My considered opinion is that God, being omnipotent, could have cut the cartoon short with the answer “Consciousness is the ability to suffer.” After all, the question itself morphed into “How do I know what suffers?”

But I would have expected God to be pleased rather than annoyed by the modified question, for it assumes that the questioner cares what suffers. Maybe, hidden in this, is the idea that consciousness is awareness of suffering, and the hint of a higher consciousness that is affected by the suffering of others. That’s not much use for brain science, but it’s got other legs.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Good point. This comic actually went through some pretty serious conceptions of consciousness. However it is a comic, so it had to be done as a gag. But I agree the guy’s question matches a lot of people’s idea of what it’s all about. Most recently Yuval Noah Harari, of Sapiens: A Brief History fame, has advocated for this definition, but it has a long history.

Of course, we then have to explain what we mean by “suffering”. My take is a system’s modeling of an automatic negative reaction within itself, one that puts stress on the system, which can’t be dismissed or satisfied. This is an arrangement that exists in biology due to our evolutionary history. It’s not entirely clear to me we’d ever need to build a machine with it, although who knows what we might discover about the engineering.

LikeLike

If the cartoon character had asked, “God, what is suffering?”, and God had given such an answer, then the panel “Thanks, God, but I think you’re missing the point” might have rested as the punch line. This is where the analytical and existential approaches to reality diverge.

If we could identify the neural correlates of suffering, I suppose we could identify those who are “faking it”, or perhaps even decide if lobsters mind being boiled alive (assuming we can correlate our correlates with their correlates). But if a machine were to identify these neural correlates, the machine would not necessarily be able to answer the question “What is suffering?”

LikeLike

I guess it depends on whether my account of suffering above is missing something. Functionally it could be, but I tend to think it covers the main bases. Of course, if you conceive of suffering having an additional fundamental essence beyond the functionality, then I can see the point. This come back to whether someone is a realist about fundamental qualia.

LikeLike

Your account of suffering is missing what is captured by, say, Ian McEwan’s novel Atonement. A similar account of jealousy would miss what is captured by, say, John Fowles’ The Magus. An account of sadness in these terms would miss what is captured by Albinoni’s famous Adagio in G minor. And so on.

Whether these concern a “fundamental essence” not captured by the biological account is a question for ontology, but something important is certainly missing. This is what I mean when I contrast the analytical and existential accounts of “reality”.

LikeLike

You might be right. Unfortunately I haven’t read those novels. I don’t guess what they capture is anything capable of being quickly summarized?

Music is an interesting case, because it raises the question of why it ends up being as emotionally powerful for us as it is. Although I think that our musical background makes a big difference. I don’t recall any music moving me as a child like it does as an adult, which inclines me to think it’s based on associations built up over time. It means that every one of us has a different experience when we listen to any particular piece.

LikeLike

The plots could be summarized, but the effect of immersion in the story cannot. It’s the immersion that matters. (I wouldn’t recommend The Magus, which I found manipulative, but it’s powerfully evocative in places. Atonement is considered a masterpiece of 20th century literature, and I would recommend it unreservedly if you have the time and inclination.)

The emotional effect of music may be cultural, but I don’t believe we learn to hear the major third as happy, the minor third as sad, the fifth as bold, or the tritone as anxious, for example on some theory that only “happy” music is played at weddings, only “sad” music at funerals, only “triumphant” music at royal processions, and so on. There is something in the intervals themselves that resonates, guiding us to employ them for certain types of occasion. I do think that humans are more sensitive to certain emotions at certain times of life. Every child knows all about rage, but nothing about teenage love, or the complex feelings evoked by poems or novels.

All of this is interesting, but beside the point. The point is that what a person, whether culturally attuned, goes through when they hear “Eleanor Rigby” cannot be conveyed to them or anyone else by describing brain processes. To identify these processes with the experience is simply mistaken, however theoretically tempting it may be within the metaphysical frame of modern science, with all its successes.

LikeLike

Your final point gets us in similar territory to our discussion on your Semantics and Consciousness posts. Short of heavily contrived scenarios like swampman or Boltzmann brains, I think the brain processes have to be considered in relation to the environment, including the body. Doesn’t mean those brain processes aren’t crucial, just that they’re only meaningful in a broader context.

LikeLiked by 1 person