A few years ago David Bourget and David Chalmers did a follow up survey to the 2009 one polling philosophers on what they believe about various questions. One of them was quantum mechanics, particularly the measurement problem and its various interpretations. Over the decades there have been surveys of physicists themselves on this question, but most, if not all, were with a very small sample size, usually only the attendees at a particular conference.

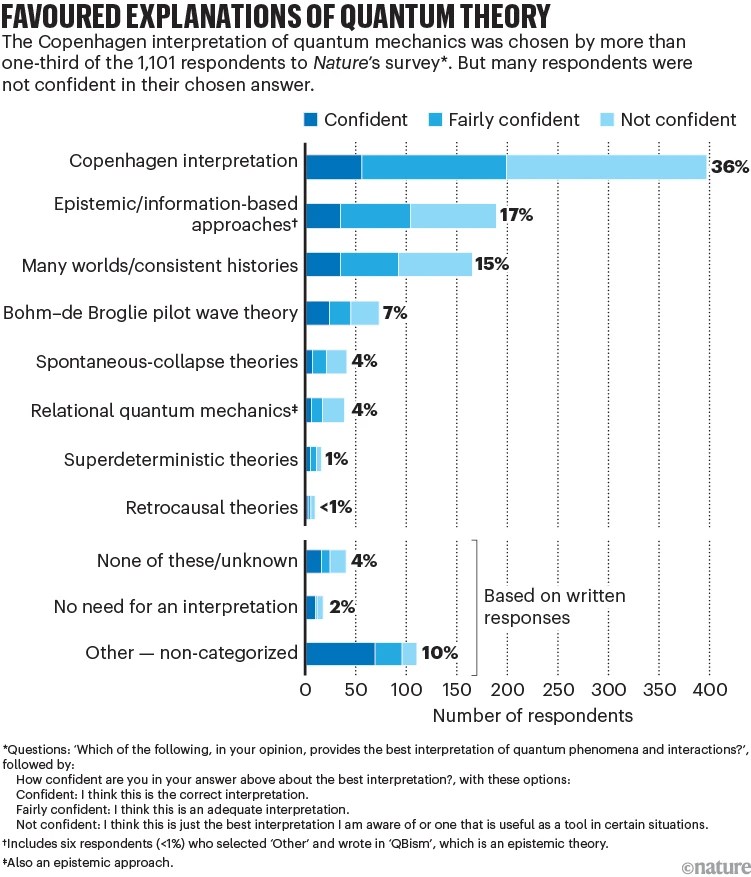

As part of the Quantum Centennial (the celebration of 100 years of quantum mechanics) Nature has done a fairly large survey of the community of quantum researchers with over 1100 respondents. The results are interesting, although not particularly surprising.

Copenhagen still comes out on top with 36%. It’s interesting that it’s stronger with experimentalists than with theorists (half vs a third). I suspect the experimentalists are hewing to a very pragmatic version of the interpretation. Which highlights a concern that the term “Copenhagen interpretation” means different things to different people. The article acknowledges this, noting that 29% of those who selected Copenhagen favored an ontic version of the wave function vs 63% who came down epistemic.

15% are Everettians (or “consistent-history” advocates, who I suspect object to being lumped in with the many-worlders), 7% Pilot-wave, 4% Spontaneous collapse, 4% Relational Quantum Mechanics, and a smattering in other views.

Overall 47% of respondents see the wave function as just a mathematical tool, with 36% taking a partial or complete realist take (my view), and 8% taking it to only represent subjective beliefs about experimental outcomes.

45% see a boundary between classical and quantum objects (5% see it as sharp) while 45% don’t (my view).

Just before the paywall, there is a question about the observer in quantum mechanics, with 9% saying it must be conscious. Another 56% said there had to be an observer, but that “observer” can just be interaction with a macroscopic environment, and 28% arguing that no observer at all is needed. (I think interaction with the macroscopic environment and the resulting decoherence is key, but it seems misleading to call that environment an “observer”.)

All interesting. Of course, how popular or unpopular a view is has no real bearing on whether it’s reality. Prior to Galileo’s telescopic observations in 1609, an Earth-centered universe was the most popular cosmology. Only a miniscule handful of astronomers accepted Copernicus’ view about the Earth orbiting the sun. Until the quantum-measurement equivalent of the telescope comes along, all we can do is reason as best as possible with the current data.

The results here are interesting to compare with what the philosophers thought on the Bourget-Chalmers survey. On quantum mechanics, philosophers were 24% agnostic, 22% hidden variable theories, 19% many-worlds, 17% collapse, and 13% epistemic. Once we take into account all the various forms of “Copenhagen interpretation”, these seem in a similar ballpark, except that philosophers are more open to hidden variable approaches. (It may be easier to favor hidden variables if you’re not the one who has to find them.)

My own view comes down to a preference for structural completeness (or at least more structurally complete models), which to me currently favors a cautious and minimalist take on the Everettian approach (as I described a few months ago). However, my credence in this conclusion is only 75-80%. That the survey indicates most physicists aren’t super confident in their own conclusions here makes me feel better.

This reminds me of a new approach that Jacob Barandes has been promoting on various podcasts (see this recent Sean Carroll episode as an example). Barandes calls it Indivisible Stochastic Quantum Mechanics. I won’t pretend to understand exactly what he’s trying to accomplish with it, but it involves rejecting the wave function completely, and replacing it with something more stochastic from the beginning. Which strikes me as less structurally complete than the wave function, and so a move in the wrong direction. But maybe I’ll turn out to be wrong.

Anyway, now we have a firmer idea of where the physics community currently stands on quantum interpretations, or at least a firmer one than we did before. How would you have answered the survey questions? (There’s actually a small quiz in the article which is worth taking to see the logic leading to particular interpretations.)

It is interesting, and possibly unexpected, that the “Not Confident” rating of the Copenhagen interpretation is greater that the totals of all others responses (save Others which is hardly a consistent group).

Again scientists are voting for “useful under some circumstances” as a criterion of a “successful” theory. It is the bare minimum we ask from a theory. It gives us something to do, even if it is not very coherent in and of itself.

The survey also shows that the field is moribund and desperately in need of a shake up. People have gotten used to having shit for explanations and that is not good.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I actually see the proliferation of interpretations as a good thing. Physicists who aren’t happy with the status quo are looking for a viable alternative. The problem is that all the viable ones fit the data (otherwise we wouldn’t talk about them anymore). So the only way to judge them is by non-empirical means, and there’s no consensus on which of those is best.

The situation in the mid 1900s was much worse. Anyone back then trying to explore quantum foundations risked their career. Even today, it’s much safer ground for philosophers than professional physicists.

LikeLike

Agreed, but many mental bones are still calcified.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Just eyeballing, it looks like most of the respondents for every interpretation aren’t confident in their choice. I don’t know if moribund is a correct description for the field. There is large amount of research, particularly relating to quantum computing, with frequent new observations that relate to the variety of explanations. The field needs a clarifying insight or experiment, but it’s been in that condition nearly 100 years. We may be at a limit in knowledge, but most people who say that kind of thing end up wrong. and the ones who aren’t wrong can’t be proven right.

LikeLiked by 1 person

“the term “Copenhagen interpretation” means different things to different people. ”

That’s so meta.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Cool write up! Don’t think I would have gone to the article, and taken the quiz you mention, without prompting. I land in the epistemic 17% or so, but prolly with leanings toward relational QM.

I have three non-mainstream takes which I’m thinking have indications as to why progress in this particular area of physics is stalling. The first take is that we cannot know the base reality, ever. This comes from Kant’s neumena/phenomena distinction. As others have said, physics doesn’t tell us what stuff is, only what it does. We can only know about things if we see how they interact with other things, and then the patterns of interaction are all we can know. So for example, there might be a large number of varieties of electron, but if we can’t come up with a way of distinguishing them, we’d never know.

The second take is that the particles of particle physics are not particles, and not recognizing that is probably holding lots of people back. Particles don’t go through two slits at once. Whatever electrons are, their pattern of interaction is altered by passing thru certain barriers (2 slits), and when they interact, they interact with one thing at a time, thus appearing to have a particle-like location. In this regard I had hope for string theory to get us another level down, but I’m not sure where that stands now.

The third take essentially derives from the second: proof of Bell’s Theorem is not proof that there are no hidden variables. It’s only proof that there are no *local* (i.e., particle-like) hidden variables. If particles aren’t particles, then that’s not a problem.

*

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks! Of course when I took the quiz I landed on many-worlds. But I went through it multiple times with varying answers to see where it landed. An interesting number of combinations came up “keep looking,” in that there was no current option to fulfill that combination.

I’m not enthusiastic about saying there are parts of reality we’ll never know, because one thing we’ve historically been reminded of repeatedly is how bad we are at predicting what we can or can’t know in the future. Some of what was unknowable to the ancient Greeks, and so just metaphysical for them, became knowable in the scientific age. It’s very hard for us to foresee the ingenuity of future experimentalists.

To your point about particles not being localized particles, I think we actually get that with an ontic wave function, where particles are actual waves. With decoherence, what manifests to us as a localized particle is a bit of momentarily pinched off wave. We get that with the mathematical structure we already have. No need for additional variables that have to be worked into all the scenarios that existing structure already works in.

My understanding of Bell’s theorem is that you can’t have a hidden variable theory without non-local interactions. Your point about the particle seems more about extent locality, an extent-localized point particle instead of a spread out entity. A spread out entity like a wave can participate in many local interactions without any of them being non-local.

LikeLiked by 1 person

The thing about the knowing part is that we can always know more. We just can’t know everything. And if we get to a point where we can’t know more, it will because we don’t have the resources (not enough in the universe) to know more, not because there isn’t more to know.

i don’t think I can buy into “momentarily pinched off wave”. How does that work? What happens to the rest of the wave? When do you see an electron participate in many local interactions?

LikeLiked by 1 person

“What happens to the rest of the wave?”

Good question. One answer people reach for it is instantly disappears from reality, resulting in the various objective collapse models.

But that’s not in the math. In the math, it all continues. But while the environment has fragmented the wave into innumerable pinched off bits, the wave has also fragmented the environment (which is just a large collection of quantum objects). So each piece of pinched off environment only gets one bit of pinched off wave. That’s what becoming entangled with the environment, aka decoherence, means.

“When do you see an electron participate in many local interactions?”

In the double slit or Mach–Zehnder interferometer experiments prior to measurement. Or in the operations of quantum computing circuits, again prior to the measurement, or some other cause of decoherence.

LikeLike

@selfawarepatterns.com

We still don't know what we don't know. But speculation makes us feel better, and in charge, doesn't it?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Remote Reply

Original Comment URL

Your Profile

I think we can say the math works. Everything else seems like speculation. But the math by itself leads to conclusions people dislike, so the speculation may be filling that role.

LikeLike

Hey, on the Barandes interview with Sean Carrol, did Barandes say that you only need the most recent “division” event to predict the probabilities for the next interaction? Or did he say that you need the current state (of the particle or field, whatever it may be) plus the last division event?

This feels important to me because in the latter case, he just doubled the amount of information required to make the predictions work. That strikes me as a major loss of simplicity and explanatory power. But in the former case, aside from whatever assumptions are needed to specify the “division” events, I don’t mind the loss of the Markovian property per se.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Honestly much of that discussion was above my head and I kind of glazed over. If this view gains any traction, I might have to go back and re-listen.

Searching the transcript, I did come across this interaction.

Although he follows that with caveats and exceptions.

I did look up the Markov assumption after his heavy emphasis of needing to avoid it, but I can’t see dumping it as an improvement. It just seems to me like an admission of an incomplete model. But I have to admit all I know about this principle is what I’ve seen in a couple of quick Googles.

LikeLike

Thanks. Note that Sean set up the question as “I already know the current state, what else do I need” and JB answered “the last division event”. But reading JB’s answer and remembering the broader context, I think he only needs the last division event, in principle. Sean just wants to start from the current state ’cause he’s stuck in the Markovian paradigm. (Not that I expect that paradigm to be wrong – but if my guess is right, being stuck there prevented his listeners from getting to a clearer understanding.)

LikeLike

He’s got a preprint out. I haven’t tried to parse it beyond the abstract, but you might find it interesting. https://arxiv.org/abs/2507.21192

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks. I hope I don’t run straight into a Far Side Moment

LikeLiked by 1 person

FWIW, I read the paper up until I got the answer to my question. Here it is:

So my guess was right – there is only one time to which we must appeal to explain any given target time (on Barandes’s view). The thing which Sean Carroll rushed past, though, is that neither the target time nor the explains-the-target time need be the present.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Marco Masi just came out with a new paper and post about this that you might be interested in:

https://open.substack.com/pub/marcomasi/p/quantum-theology?r=schg4&utm_medium=ios

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for the share. Theology isn’t really my thing (except as an anthropological/sociological phenomenon), and historically attempts to tangle it up with science never turn out well in the long run.

LikeLike

The more I learn about quantum physics, the more I agree with the old “shut up and calculate” mantra. My main issue is this: every interpretation of quantum physics gets exploited by pseudoscience somehow, which makes me very skittish about buying into any particular interpretation.

LikeLiked by 2 people

I can understand that. And “shut up and calculate” has its uses. But trying to understand the reality is irresistible for me, which as far as I can see can’t be done without metaphysical implications. And in the end, the quacks and shysters are going to misuse it no matter what do.

LikeLiked by 1 person

What struck me about that survey was just how clueless we really are about QM. “Shut up and calculate” works great, which may explain the preference for the Copenhagen Interpretation, but it’s very unsatisfying as a theory.

FWIW, from what I’ve read, most use the term “measurement” rather than “observation” for exactly the reason you touch on. An “observation” implies a person.

(Also FWIW, I lean towards the Diósi-Penrose model of objective collapse. I do not think wavefunctions apply meaningfully to large objects for a variety of reasons, but like everyone else, I’m just guessing.)

LikeLiked by 1 person

Good point on “measurement.” The “measurement problem” does sound less spooky than the “observer problem.”

(Definitely, until we have more data, we’re stuck. Still, it is fun to do the guessing.)

LikeLiked by 1 person